DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Charlottesville didn’t rip open a deep American scab last month. For a scab to be ripped open, it would have had to have time to heal.

“This is not new. Not to me, anyway,” said DCPA Theatre Company Associate Artistic Director Nataki Garrett, an African-American woman. “The marching you saw in Charlottesville has been happening every single day of my life. It is only new to eyes that have been willfully blind to it.”

Dee Covington, Sean Scrutchins and Erik Sandvold in Curious Theatre’s ‘Appropriate.’ Photo by Michael Ensminger.

But the festering racial divide that was exposed on the streets of Virginia was given a horrifyingly modern face by the dozens of white supremacists who did not even feel the compunction to cover their heads, as their forebears often did decades before while burning crosses and lynching African-Americans under anonymous hoods and cloaks.

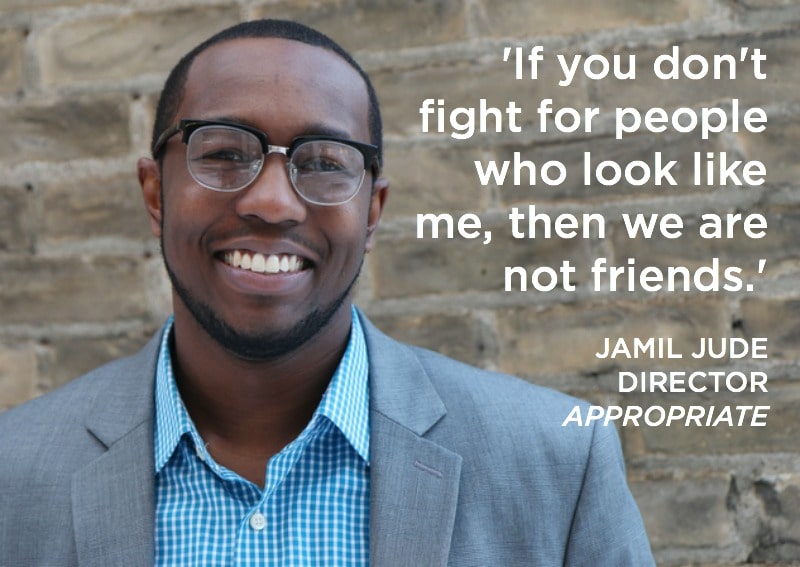

Jamil Jude, the Associate Artistic Director at Kenny Leon’s True Colors Theatre in Atlanta, was in Denver the day James Alex Fields Jr. allegedly plowed his Dodge Challenger into a crowd of Virginia pedestrians, killing counter-protester Heather Heyer and injuring 19 others. Jude was here rehearsing Curious Theatre Company’s incendiary new family drama Appropriate, which introduces Colorado theatre audiences to rising young playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins.

No one in Colorado knows the MacArthur Genius better than Jude and Garrett, who have a broad range of separate and shared experiences directing his work at theatres around the country.

Jacobs-Jenkins’ six published plays all address race relations in some way, Garrett said. Neighbors, for example, from a strictly black perspective. An Octoroon from the lens of American history. And Appropriate, which plays at Curious through Oct. 14, from an entirely white lens. And while the three plays do not constitute a trilogy, Jude says, they could serve as one.

In Appropriate, three adult, estranged siblings descend on a crumbling Arkansan plantation to liquidate their dead patriarch’s estate. He was a powerful man who graduated at the top of his Harvard law class and was on his way to becoming a Supreme Court justice when he died. But when his children find gruesome Southern artifacts among his belongings, they are forced to question who this man was, and the bigotry they have descended from.

“This family’s legacy is exactly what marched down the street in Charlottesville, and in Berkeley, and tried to do the same in San Francisco and Boston,” Garrett said.

Nataki Garrett and Jamil Jude.

Enter, into Denver, the work of Jacobs-Jenkins, whose Neighbors is a scathing satire of black entertainment though an uncouth family of black actors named the Crows who perform in blackface. He rose to national prominence with An Octoroon, a modern riff on Dion Boucicault’s 1859 classic melodrama that makes for a subversive take on race in America then and now.

“The throughline with all three plays is that in the American zeitgeist, there is this need to have conversations around race in which ‘The Other’ does not exist,” said Garrett, who will be directing Lydia R. Diamond’s racially charged Smart People for the DCPA Theatre Company in October. “So when you say, ‘I am not a racist,’ or, ‘I don’t see color,’ that requires ‘The Other’ to not exist. What Branden’s plays all suggest is that you can’t have one without the other. You cannot live outside of that.”

To theatre audiences, Appropriate might seem to be a racial incongruity. Jacobs-Jenkins has been hailed as one of the essential new African-American voices in the American theatre. But you won’t see an African-American actor on stage at Curious Theatre. And that, said Jude, is by design. Garrett, who has directed both An Octoroon and Neighbors from Washington D.C. to Los Angeles, says that in a metro area like Denver where the population is only 10 percent African-American, it just makes practical sense to introduce audiences to Jacobs-Jenkins’ work with Appropriate.

Garrett recalls a recent evening attending a local theatre production accompanied by Denver Center CEO Janice Sinden, who is white. “A very nice white woman approached me and asked, ‘How did you get here?’ ” Garrett said. “She didn’t ask Janice that question. She asked me. I didn’t know how to answer her, so I just said, ‘I got into my car and drove here.

“So you can’t just start all the way over there,” Garrett added. “You have to condition all of your audience to be able to sit in that room together. And that means you need a few more plays before you get there.”

Jude believes Jacobs-Jenkins has plenty to say about race from the perspective of white characters, but he said there is an elephant in the room, and it is most definitely white. “Appropriate will be one of the most-produced plays in America over the next two to three years, and that is absolutely by his design,” he said, “because it is a play that talks about race – and you don’t have to hire any people of color to do it.”

That is not the case at Curious though. Jude said it was important to the company that it hire an African-American to direct the play. And it was important for Jude to bring more people of color inside the creative process. His assistant director is acclaimed area actor Jada Dixon (who will be appearing in Boulder Ensemble Theatre Company’s upcoming The Revolutionists), and he invited in several recent college graduates to assist and learn in various ways.

Jude assumes and accepts that the majority of his audiences for Appropriate will be white. And given the freshness of Jacobs-Jenkins’ voice, they might be surprised, he said, by just how traditional Appropriate will seem to them, at least in form. This is a classic living-room family drama that Jacobs-Jenkins says he gleefully ripped off in style from Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, Sam Shepard and Tracy Letts. Academics call the living-room drama “an inherited form,” and borrowing from that form, Jude said, is also by design.

“When you look at some of the great plays of the past century, the issue of race is so deeply rooted into these characters, even though it is never discussed that way,” he said. “We never go out of our way to say, ‘Oh this is a white Southern experience,’ or, ‘This is a white Northern experience.’ We just assume that it is. I think this is Branden’s way of saying, ‘I am going to appropriate this form, and I am going to use it to have a deeper conversation with you about race. We’re bringing all of that to the table, so you can’t circumvent it. You have to embrace it. You have to investigate it.”

And there is that key word: Appropriate.

The title of the play is very much a double entendre. There is “appropriate,” as in, “suitable for a given occasion.” And there is the alternately pronounced take on the word meaning “borrowing (or stealing) from a particular person or culture.”

“This play is definitely, intentionally both,” said Jude. “He’s very much saying, ‘This is the conversation I want to have. You all have identified me as a black playwright, and anytime I write something, you say that it is racially charged. Well, then, I am going to use the most American of play forms – the living-room drama – and I am going to have a conversation about whiteness and race using that very form.”

But if a familiarity with the form momentarily lulls the audience into a false sense of comfort, Jude says, just you wait. “He challenges that (bleep) right away,” he said. Like two pages into the script.

“Even as the lights start to go down, you are immediately made to feel slight discomfort that will grow throughout the play, regardless of who you are. I don’t know if we ever get comfortable.”

Those white supremacists were certainly marching comfortably in Charlottesville last month, “and that’s because Donald Trump has allowed them to feel comfortable,” Jude said. “What needs to be unmasked now are not the names of individual protesters but rather those people who are in positions of real power, especially in the judicial system, who hold these personal prejudices and apply their power in ways that are abusive and unjust. It is the system that is the problem, not the people inside of it.

“In this play, we see a family that is wrestling with the question, ‘What do I do with the legacy that has been passed down to me?’ And we see them constantly fail to eradicate the system they come from.”

Jacobs-Jenkins’ plays are a gift to his audiences, Jude said. “He gives audiences a chance to investigate their own family origins and then hopefully inspire them to do something about it,” he said.

Mare Trevathan, Rhianna DeVries and Audrey Graves in Curious Theatre’s ‘Appropriate.’ Photo by Michael Ensminger.

“I hope people walk out of this play and then ask their parents deep questions about where they came from and how they were raised,” he said. “I don’t feel like we can actually address issues around systemic injustice, police brutality and inequality until we start to clean up our own houses. You have to clean your own closets before you can go somewhere else and start to address it.

“I hope when people walk out of this play, they really question what is happening in their own families. I hope they say, ‘Uncle Frank says some really sexist stuff. How can I challenge my own sexist ideologies so that I can then challenge Uncle Frank? Then, when my kids see Uncle Frank being sexist, they might not think that’s funny.’ ”

Little frustrates Jude more than white friends telling him they just can’t talk to their conservative family members at the holidays.

“Listen, you are not my ally if you can’t talk to your own family member about me at your dinner table,” Jude said. “Because if your family member is racist, or if your family member believes in building a wall on our Southern border, then they are never going to let my black (butt) at their dinner table so that I can try to challenge their notions myself. So, don’t tell me you are my ally when you don’t fight for me in my stead. If you don’t fight for people who look like me, and you choose to pass the buck and hope that somehow, through osmosis, your family members can change, then we are not friends.”

And until we can engage in those deeper conversations, Garrett said, “We are kind of screwed as a nation.”

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theater critics in the U.S by American Theatre Magazine in 2011. He has since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center’s Senior Arts Journalist.

• Presented by Curious Theatre Company

• Sept. 2-Oct. 14

• 1080 Acoma St.

• 303-623-0524 or curioustheatre.org

• Playwright: Branden Jacobs-Jenkins

• Dee Covington: Toni

• Erik Sandvold: Bo

• Mare Trevathan: Rachel

• Sean Scrutchins: Frank

• Alec Sarché: Rhys

• Rhianna DeVries: River

• Audrey Graves: Cassidy

• Harrison Lyles-Smith: Ainsley

Creatives:

• Jamil Jude: Director

• Markas Henry: Scenic Designer

• Kevin Brainerd: Costume Designer

• Richard Devin: Lightning Designer

• Jason Ducat: Sound Designer

• Kristin MacFarlane: Props Designer

• Dane Torbenson: Fight Choreographer

• Jada Suzanne Dixon: Assistant Director

• A. Phoebe Sacks: Stage Manager

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!