DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

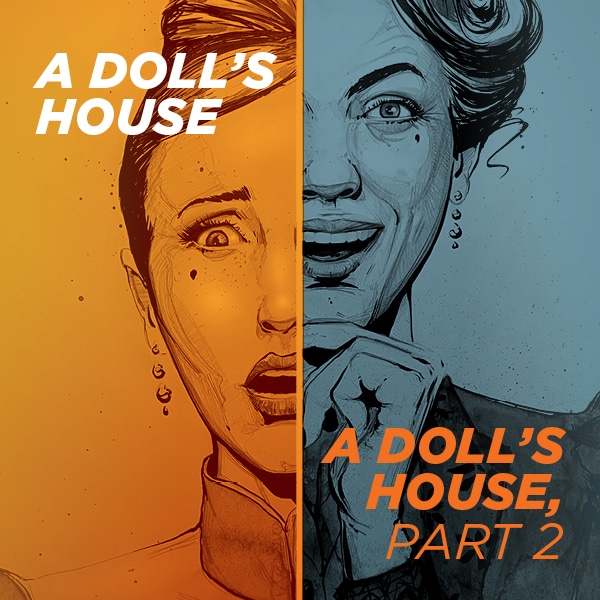

Marianna McClellan, left, and Barbra Wengerd bring very different styles and energy to the role of Nora – and that’s on purpose. Photo by Adams VisCom

Asking an actor to age 15 years during the course of a play is not an unusual theatrical challenge. But DCPA Theatre Company Artistic Director Chris Coleman and his Associate Artistic Director, Rose Riordan, had a clear intent in wanting two actors to share the role of Nora Helmer in the company’s history-making stagings of A Doll’s House and A Doll’s House, Part 2.

Much happens to the iconic runaway wife and mother in the 15 years after she blows out of her family’s life and into a world that offered very few possibilities for a single woman in 1879. Coleman thought it was essential to have different actors play Nora to emphasize not only the physical changes she would have undergone in that time, but to underscore the idea that Nora comes home a truly different woman: A confident force to be reckoned with.

“When Nora comes back, she’s a changed person, down to her bones. And that was the goal.” Barbra Wengerd

“For those who watch the original A Doll’s House, I really do not want it to feel like it’s a foregone conclusion that Nora is going to find the backbone to walk out that door by the end of the play,” Coleman said. “I want her to feel like someone who is still finding her core. That Nora needs to be somebody young enough to still be in formation. That is such a stark contrast to the Nora we meet in Part 2, and I think we need to honor their differences.”

So Denver Center audiences meet actor Marianna McClellan in Henrik Ibsen’s 1879 classic A Doll’s House, and Barbra Wengerd in Lucas Hnath’s 2017 sequel A Doll’s House, Part 2. In terms of their look, energy and sound, these are two very different women and actors.

And while McClellan says with a laugh: “I think either Barbra or I could have done both plays,” she concedes, “that would be a lot for one person.”

Not only because that would mean essentially learning two entire plays. “The language in both plays is very different,” McClellan said. The original is the prototype of a classical world drama. Ibsen wrote it in his native Norwegian. Hnath, an American, appropriately sets his sequel in 1894, but gives his characters a decidedly contemporary vernacular. “The plays are stylistically so different that part of the whole idea is to juxtapose two very different actors,” Wengerd said.

Nora blows those doors right back open at the start of ‘A Doll’s House, Part 2.’ Photo of Leslie O’Carroll and Barbra Wengerd by Adams VisCom

The Nora introduced by Wengerd in Part 2 is not the same Nora we met in the original, and that is by design. “I think Nora is one person when she’s in the house and under the influence her husband,” she said. “And then so much happens to her over the course of the next 15 years that she has literally reinvented herself. She is constituted differently when she comes back. She’s a changed person, down to her bones. And that was the goal.

“I think that’s the whole point of Part 2. It’s saying that if these women were not trapped in their marriages, they would literally be completely differently women.”

For that reason and more, the two actors did not study one another’s choices in rehearsal to pinpoint inflections or mannerisms the actors perhaps should share in their performances. For one thing, they didn’t have time to watch each other rehearse. They had their own plays to prepare. But more to the point, their directors did not want mirrored performances.

“Although playing Nora in Part 2, I feel like I have more of an obligation to track what Marianna’s coming up with,” said Wengerd. “That’s a wonderful opportunity, because through Marianna, I get to experience the full emotional journey of everything that catapults us into Part 2 – and her work is so good.”

Wait, how did Henrik Ibsen become a feminist in the first place?

While audiences have the opportunity to see both plays because of the Denver Center’s unprecedented repertory presentations of both plays (and back-to-back if they attend on cerain weekdays), the actors say is not necessary to see both plays to enjoy either individually.

“As you can imagine, the first one definitely informs what happens in the second one,” said Wengerd, “although, the second one will still make sense if you haven’t seen the first one.” That said, those who do see both, she added, are in for a rare theatrical treat.

“This will be such a rich experience for people who attend both plays,” she said. “You get to see a classic followed by a contemporary comment on a classic. These are two rich, emotionally provocative and thought-provoking pieces. I think they both ask some huge questions, and I don’t know that either of them provides any definitive answers.”

And McClellan has a rather unorthodox suggestion for whom women might want to bring with them to the thatrical double-header.

“Oh, I think this would be a great first date,” she said. “Seriously, think about it: If you watch these two plays together, you are going to get the heart of things right away. Then on the way home, you get to have a really strong conversation where you answer all the important questions about what you think about relationships. And if after all that you still want to look that other person in the eye … then you’re good.”

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theater critics in the U.S. by American Theatre Magazine in 2011. He has since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center’s Senior Arts Journalist.

Here are more of Marianna McClellan and Barbra Wengerd’s thoughts on the character they share:

Marianna McClellan: It’s frustrating to me because Nora is fed this information from her husband, from her father, from what society has laid out for her and she’s trying to function within the world she’s been given – and yet she can only go so far. Ibsen said: “A woman cannot be herself in the society of present day, which is an exclusively masculine society, with laws made by men, and with prosecutors and judges who assess female conduct from a male standpoint.” So he was basically saying that women are living in a man’s world, and that is shockingly still true today, 140 years later. That is upsetting to me, and it’s good that we’re continuing to examine these things.

Barbra Wengerd: Women at that time were stripped of any kind of political or legal power. But when human beings know we need something, we’re going to do it. And Nora ends up having to do some really compromising things to save her husband and family. When you put people in the position of saying, “No, you can’t have what you need,” people are going to do what they have to do to get it – and that oftentimes means be dishonest.

Marianna McClellan: I think Nora operates like a game of Jenga. I keep having this image where she keeps pulling from different parts and stacking them up higher. And you know what happens in Jenga? It all crashes down eventually. But then she gets to rebuild some version of herself. She’s got to keep going. She’s got more blocks, and she’s got to keep stacking them.

Ticket information

Ticket information