DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

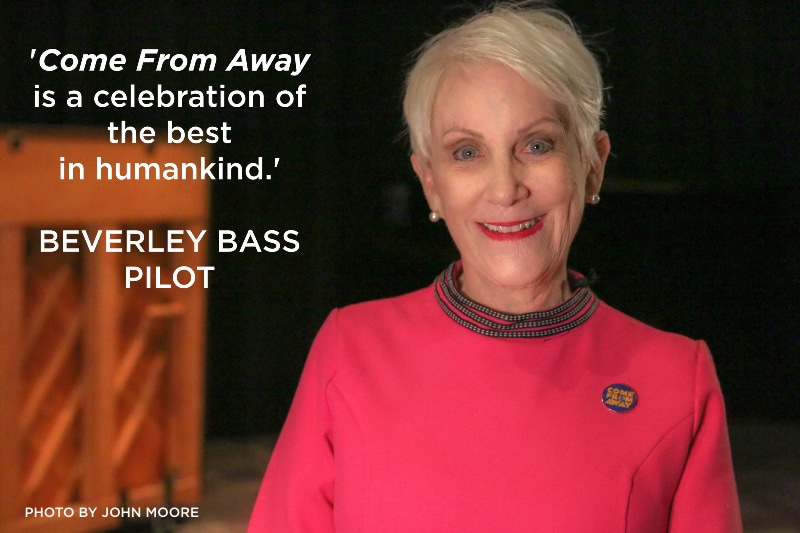

“This is not the story of 9/11,” Beverley Bass says. “It is the story of 9/12.” Interview by John Moore. Video by David Lenk.

On one of the most horrible days in human history, pilot Beverley Bass landed her Boeing 777 in what she calls “the most peaceful place on the earth.” It was not at her intended destination of Dallas. It was on the tiny island of Newfoundland.

The First North American Tour Company of COME FROM AWAY, Photo by Matthew Murphy, 2018

For Bass, September 11, 2001, began “as an extraordinarily beautiful morning” in Paris. She was uneventfully carrying 158 passengers 35,000 feet above the Atlantic Ocean with her feet propped up on the dash when she got the call that an airplane had hit the World Trade Center in New York. Concern turned to alarm 20 minutes later when the second tower was hit and with that came the word “terrorism.” “Things became very different at that time, obviously, in our cockpit,” Bass said on a recent visit to Denver.

U.S. airspace was immediately closed and 38 in-bound commercial pilots were ordered to land in the small Canadian town of Gander to wait out the confusion. Most pilots go their entire careers without ever landing in Gander. But they all know an order to divert there means one thing, Bass said: An emergency is unfolding somewhere.

Within three hours, this remote aviation town of 9,000 was joined by nearly 7,000 involuntary visitors who would need to be clothed, housed and fed for the next five days. What happened next became the basis for the Denver-bound, Tony Award-winning Come From Away, a musical Bass emphatically says is not the story of 9/11. “It is the story of 9/12.

The North American Tour of COME FROM AWAY, Photo Credit Matthew Murphy

“It is a celebration of the best in humankind,” she said.

Bass was the 36th of 38 pilots to land at Gander. Little did she know when she landed after eight hours in the air that no one would be allowed off the plane for another 19 hours because there was simply no place for them to go. And because cell phones were not yet prevalent no one knew the full extent of what was happening in New York. Some, Bass said, must have assumed World War III had broken out. “It was just a very, very hard night,” she said.

But when they finally got off the plane at 7:30 the next morning, Gander revealed itself to be a kind of Brigadoon. “I can still remember walking into the terminal and just seeing it lined with tables and tables of food,” Bass said. “The people of Gander had stayed up literally all night cooking. It was incredible.”

The spontaneous relief effort was called Operation Yellow Ribbon. Because passengers were not allowed to access their luggage, Gander residents brought diapers and baby formula to the airport. They filled 2,000 prescriptions. They brought inhalers and insulin needles and anything else they thought might be needed. Local merchants cleared their shelves without taking inventory. Gander is a town with only 500 motel rooms, so residents took strangers back to their homes to shower. One local veterinarian took charge of feeding the hundreds of animals that were locked away in airplane cargo holds.

Bass was the 36th of 38 pilots to land at Gander International Airport on September 11, 2001.

Bass does not consider herself a specifically religious person, but she considers Gander to be a holy place. She and her husband, Tom, have been back five times, and they seriously considered moving there after they attended a massive 10-year reunion in 2011.

Read more: Bass’ response to seeing her story come to life in Come From Away

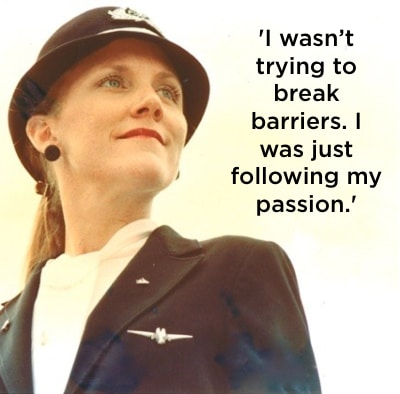

Bass, now 66 and retired, made history as the first female captain at American Airlines in October 1986, when she was 34. The next month, she led the first all-female crew in the history of commercial jet aviation on a flight from Washington, D.C. to Dallas. But she does not consider herself a pioneer. She considers herself a pilot. She has ever since she was four, when she saw a statue of Icarus

in her hometown of Fort Meyers, Florida. At eight, Bass’ aunt would take the girl out to the airport at night just to watch the landing lights. At 16, she begged her father to let her take flying lessons, but he wanted her to focus on the family horse trade. So when she turned 18, she signed up for flying lessons herself. “When I came home from my first lesson, I walked into the house and told my parents I’ll fly for the rest of my life,” she said. And she has.

Beverley Bass was hired by American Airlines in 1976.

At the time, Bass didn’t even know what a glass ceiling was.

“I wasn’t part of the women’s movement,” she said. “I wasn’t part of the Gloria Steinem crowd. I wasn’t trying to break barriers. I was just following my passion. And my passion was to fly the biggest airplanes I could fly.”

But at the time, Bass had few role models. “Most of the time when women put applications in to the airlines, they were simply rejected,” she said. Until 1976, when Bass became the third female pilot ever hired by American Airlines. “They had 10,000 applications for pilots that year, and they hired 87,” she said. “You had to be qualified, or you weren’t going to be part of the group.”

In the five days Bass was grounded in Gander, her Boeing 777 and others began to sink into runway asphalt that was never intended to bear so much weight. A hurricane was approaching. Bass was eager to return to the skies. “I never once thought about not flying again,” she said. “I was not going to let that event ruin what I have loved so much for my whole life. And it never, ever affected me on any of my flights afterward.”

She did not have lingering anger issues that the terrorists had used the planes she loves as killing machines. “But what did happen to me is for 90 nights I woke up in the middle of every night, hoping it wasn’t true,” she said. “Thinking: ‘Please. This did not happen.’ And then, after three months … I was OK. I don’t know why.”

What has helped since, she says like the proud groupie she is, has been Come From Away, which as of May, Bass had seen in performance 101 times.

“It is such a happy show,” she said. “It’s a story that wouldn’t exist without the events of 9/11, but it was really written about the kindness and generosity that was bestowed upon us when we descended into the beautiful town of Gander.

“One of my favorite lines from the show is when one of the passengers — his name is Bob — has come back from Gander. And his father asks, ‘How were you when you were stranded?’ And Bob says, ‘How do I tell him? Not only was I OK. I was so much better.’”

DETAILS

DETAILS

Come From Away

October 4-9, 2022 · Buell Theatre

Tickets

John Moore: Take us through the start of your flight on September 11, 2001.

Beverley Bass: We’d had a great layover in Paris. The crew all went out to dinner the night before. I guess the very first thing that should be recognized is we did not depart Paris on time. If we had, I wouldn’t be a part of this story. So the fact that we left almost two hours late changed everything for us.

John Moore: Why were you two hours late that day?

Beverley Bass: Four of the eight lavatories on our airplane were inoperative, which is normally not a problem for us. It’s a 10-hour flight home and I didn’t have a full airplane. A full airplane would’ve been 247 passengers, but I only had 156 that day. I tried to get the lavatories fixed in Paris, but you usually can’t get anything fixed on the Europe side. They always wait until the airplane comes back home and they fix the problem stateside. So I had to leave Paris late, with just four lavs, not realizing at the time that we were going to be on the airplane for 27 hours.

John Moore: When did you know that something was wrong?

Beverley Bass: We were coming up on the midpoint of the North Atlantic crossing for us. We have an air-to-air frequency that all pilots are required to monitor over international waters because we’re out of range of air traffic control. It’s a frequency where we just kind of chit-chat with each other over flight-related things. It was on that frequency that one of the other pilots said that an airplane had hit the World Trade Center. And of course, being pilots, we chatted about it. We thought it must have been a light airplane but we also knew the weather was great in New York, so we couldn’t imagine why that would happen. You’d never dream it would be airliner. That just wouldn’t even cross our minds. Then about 20 minutes later, we got word that the second tower had been hit. The next thing we heard was that the New York airspace was going to be closed, but that really wasn’t a factor for us because normally we come in way over northern Canada and over the Chicago area. And then of course, all U.S. airspace was shut down, and that’s when we went into planning mode for a diversion. We called up our lead flight attendant and told her what had happened. And by now we’ve received a company message across the printer in the airplane, and I told everyone in the cockpit that we were on lockdown. We just assumed we would be sent to one of the major cities in Canada. We had enough fuel to get to Toronto, Montreal, Calgary or Edmonton. Shortly after that, we were ordered to land in Gander, and to do so as quickly as possible.

Beverley Bass: We were coming up on the midpoint of the North Atlantic crossing for us. We have an air-to-air frequency that all pilots are required to monitor over international waters because we’re out of range of air traffic control. It’s a frequency where we just kind of chit-chat with each other over flight-related things. It was on that frequency that one of the other pilots said that an airplane had hit the World Trade Center. And of course, being pilots, we chatted about it. We thought it must have been a light airplane but we also knew the weather was great in New York, so we couldn’t imagine why that would happen. You’d never dream it would be airliner. That just wouldn’t even cross our minds. Then about 20 minutes later, we got word that the second tower had been hit. The next thing we heard was that the New York airspace was going to be closed, but that really wasn’t a factor for us because normally we come in way over northern Canada and over the Chicago area. And then of course, all U.S. airspace was shut down, and that’s when we went into planning mode for a diversion. We called up our lead flight attendant and told her what had happened. And by now we’ve received a company message across the printer in the airplane, and I told everyone in the cockpit that we were on lockdown. We just assumed we would be sent to one of the major cities in Canada. We had enough fuel to get to Toronto, Montreal, Calgary or Edmonton. Shortly after that, we were ordered to land in Gander, and to do so as quickly as possible.

John Moore: But you had your own diversion to make first.

Beverley Bass: Yes, I was actually number 36 out of 38 to land in Gander, and the reason I was so late is that I was a little bit overweight for landing. I elected to jettison 7,000 pounds of fuel so that when we landed, we would be touching down at our appropriate landing weight. But I also didn’t know how much fuel would be available in Gander whenever we did leave. So I was wrestling with: Do I land overweight, or do I jettison the fuel? And I elected to jettison. That took a little bit of time, and when I came over the threshold I looked out both sides of the airplane and there were literally cars lined up on the side of the road for as far as I could see. I honestly thought everybody in Newfoundland came to see what was going on at the airport because really since World War II, there had never been that many airplanes on the ground there at once, and certainly not wide-bodies. The airplanes were literally parked like sardines, nose to tail. They were on every piece of concrete. They were on taxiways. They were on runways. After we landed, an (airline official) came onto our airplane and the very first question he asked me was, ‘Did you land overweight?’ And I said, ‘No.’ And he said, ‘Thank you.’ So that ended up being a good decision — but I didn’t know it at the time.

John Moore: What was it like being stuck on that plane for almost another full day?

Beverley Bass: We landed at 10 o’clock in the morning, and so when they said, ‘You will not be getting off the plane until tomorrow,’ we knew we were in for the long haul. Of course, it was up to the flight attendants to figure out how they were going to entertain the passengers. We only had one meal service left, so the attendants treated that like breakfast, lunch and dinner. They gave the passenger their meal, blankets and pillows; put movies on; and put them to bed, basically. The cockpit crew stayed awake all night listening to the news. The only feed we were able to get was the BBC, so we only had London’s version of what was happening. A few passengers had cell phones but only a very few, and they had no way to charge them, and everybody was running out of battery power. A few people had learned from their offices and relatives what was happening, but it was so unreal to us because it wasn’t like we were able to watch it on TV or see it unfold.

John Moore: As the days and weeks and years went by after 9/11, tell me about your own recovery, balanced against this wonderful, life-affirming experience in Gander?

Beverley Bass: Well, probably the best thing that happened is that every trip I flew after 9/11, the crew knew I had been diverted to Gander that day, and they always want to hear the story of what it was like to be there. So for years, I had the opportunity to share that story with my fellow crew members. But you have to remember that when it was happening, I did not have the opportunity to mingle around the town. I was pretty much sequestered in the Comfort Inn, because I never knew when I was going to get the call from American to fly again. I could not venture off too far because if that call came through, I needed to be there. And so really until the musical came out, there were a lot of things that I didn’t know anything about. I didn’t get to meet a lot of the people who I have since become very close friends with.

John Moore: There were some people, both passengers and flight attendants, who decided never to fly again after 9/11.

Beverley Bass: And I was the complete opposite. I called American Airlines the minute I got home to Dallas, and I said, ‘I want to fly the first flight you have out of here.’ I was dying to go right back out. I never once thought about not flying again.

John Moore: What was it like meeting the woman who is still playing you on Broadway, Jenn Colella?

Beverley Bass: In the summer of 2015, we got a call from the producers inviting us to the musical in San Diego. So off we go to the La Jolla Playhouse, and we do not know one thing about the show. There was a party the night before, which was actually their last preview performance. I walk in with my husband and my daughter and I spotted Jenn across the room. I had seen her picture on Facebook. I was petrified but I went up to her and said, ‘I think you’re playing me.’ And she said, ‘You don’t say?’ She was so cute. And we have just become kindred spirits ever since. We’re very close. We text. We email. I even cut my hair short to be like hers.

John Moore: And how would you describe seeing the performance the next night?

Beverley Bass: We were front row, center. And we had no idea what we’re getting ready to watch. And a few minutes into the show, Jenn she rolls out in her chair. She’s sitting there in my uniform jacket, and she picks up the phone and says, “Tom, I’m fine.” Well, my husband buried his head in his hands. I mean, we probably missed 75 percent of the first show because we were sobbing. We were crying because it was so well done and we couldn’t believe how true it was. They wrote the song ‘In the Sky,’ which is my whole flying life in one song. Who would have ever thought?

John Moore: Come From Away has been received by critics and audiences as a cathartic reminder of the capacity for human kindness in even the darkest of times, and the triumph of humanity over hate. How do you describe Come from Away for the people who see it?

Beverley Bass: I think the show teaches you that a little bit of kindness can really go a long way — and I know it has changed me immensely. Texas was so ravaged by hurricanes last year. Before, I would watch it unfold on the TV news and feel terrible for everything that’s happening. But now I go to the shelters and I go to work. That’s really what the show has taught us: It doesn’t take much to be kind to one another.”