DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

From the archives: this article was originally published on August 14, 2019

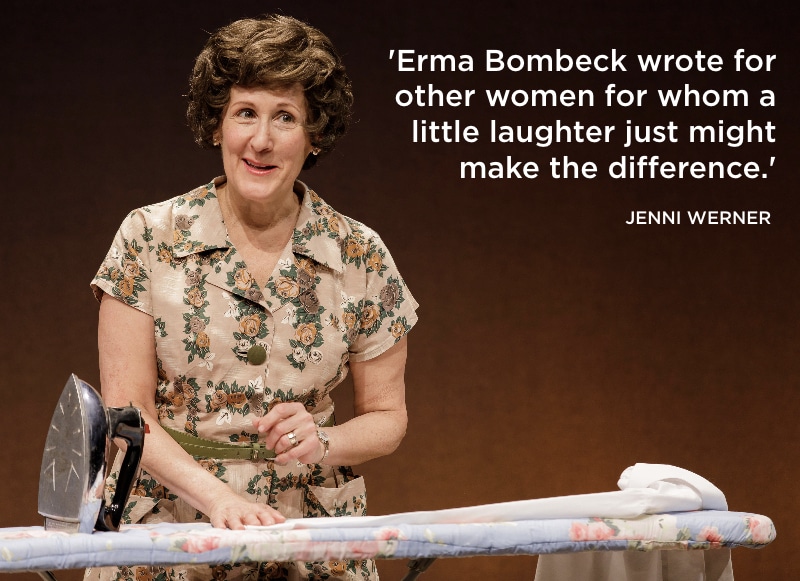

Pam Sherman as Erma Bombeck. Photo by Goat Factory Media Entertainment.

In many ways, humorist Erma Bombeck was a woman ahead of her time. She wrote more than 4,500 nationally syndicated newspaper columns over 31 years, had a regular television spot for 11 years, wrote 12 books, nine of which were New York Times bestsellers, and joined with other women to fight for equality, all the while raising a family and becoming a savvy businesswoman. She inspired women all over the world to find humor in their lives and share that humor with others. Of course, this represents only part of a very full life. But especially when we look at her literary achievements in the context of women in publishing, Bombeck’s career highlights are significant.

Erma Bombeck.

Pam Sherman will explore the story behind America’s favorite average housewife in her one-woman show Erma Bombeck: At Wit’s End, running September 4-22 at the Garner Galleria Theatre.

Women have worked in journalism in the U.S. as far back as the colonial period, primarily at newspapers published by their male relatives. In the 1880s, women in both the U.S. and the U.K. began to apply for newspaper positions in great numbers. But male journalists didn’t welcome them with open arms. Not only did they feel that women “lacked the nose for news,” but they insisted that allowing women to become reporters would de-feminize them. So while some women in the 19th century did join the newsroom, they weren’t taken seriously and were often relegated to reporting on fashion, beauty, household tips and society news. Women – journalists and readers alike – were expected to stay in their separate spheres of interest, and leave the men to consider serious issues.

The exception to this rule, of course, were the mid-19th century periodicals published by U.S. textile mill workers and the suffrage journals, which advocated for women’s right to enfranchisement and offered women a vehicle to redefine themselves. These were the forerunners of the women’s liberation periodicals of the 1970s and 80s (think Ms. Magazine and her sister publications). The common denominator among these publications was that they were women writing for women – still separate spheres.

Actor Pam Sherman. Photo by Brandon Vick.

The women’s liberation publications of the ’70s were part of Second Wave Feminism, a movement whose origins are frequently credited to Betty Friedan’s book, “The Feminine Mystique,” published in 1963. Originally intended as a short article, the piece took on its longer book format when no magazine would agree to publish it. The book began with a chapter on “The Problem that Has No Name,” by which Friedan referred to frustrated housewives who wanted more than their family life to keep them fulfilled. “The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women,” Friedan began. “It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the 20th century in the United States. Each suburban housewife struggled with it alone. … As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night – she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question – ‘Is this all?’ ”

Critics, however, included housewives who felt belittled by Friedan, like Bombeck herself. In 1964, the year after the publication of Mystique, Bombeck’s children were all in school, and she started writing her breakout column in the Dayton-Journal Herald, “At Wit’s End.” The column was successful precisely because she wrote about family life with humor, giving voice to everyday suburban women who’d never seen themselves represented in the media. Freelance writer Kristen Leviathan says Bombeck “turned the image of the 1950s happy homemaker on its head, inviting women to identify with her experiences and take a closer look at their own. She shed light on the less glamorous elements of house-wifery, critiquing a cultural institution in ways different than Friedan, but perhaps just as revolutionary.”

But as Erma herself expressed, she wasn’t writing to create a revolution. She wrote to help other women like her, other women with families who struggled to get through the day, for whom a little laughter just might make the difference. As she wrote in her book “At Wits End,” “I will have to admit that I wrote this book for the original model – the one who was over-kidsed, under-patienced, with four years of college and chapped hands all year around. I knew if I didn’t follow Faith’s advice and laugh a little at myself, then I would surely cry.”