DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

This article was published on September 16, 2019

Inmates at the Sterling Correctional Facility participate in a theatre class through the University of Denver Prison Arts Initiative.

But for a few fleeting recent hours inside the maximum-security prison that has housed him for the past 20 years, the convicted killer from Douglas County was being watched with empathy and respect. Maybe for the first time.

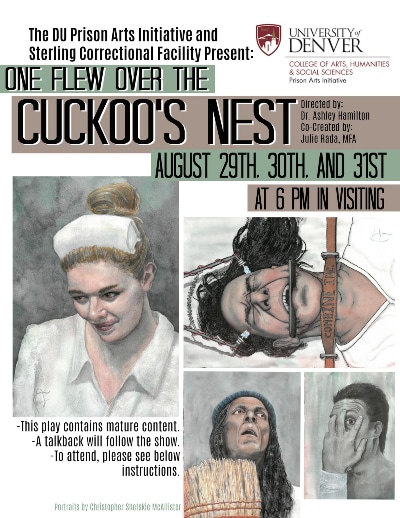

Those watching were an overflow audience of fellow inmates, corrections officers and members of the public who had driven to the Sterling Correctional Facility 120 miles northeast of Denver to see the subversive counterculture classic One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, a 1974 Pulitzer Prize-winning play about mental patients confined to a psychiatric hospital. Here, through the growing University of Denver Prison Arts Initiative, the play was being presented and performed by inmates at Colorado’s largest state prison.

And Ybanez, who had never performed before in his life, was acting his guts out. To anyone who followed his trial in 1999, the moment of pretend that was playing out was as real and riveting as any Broadway performance.

Ybanez was playing the paralyzingly shy mamma’s boy, Billy. In the story, when the diabolical Nurse Ratched catches virginal Billy alone with a woman and promises to tell his overprotective mother, the stuttering Billy wrenchingly begs of her: “P-p-p-please, du-du-don’t t-t-t-tell m-m-my muh-muh-muh-mummy!” Her mere threat drives the boy to slit his throat from guilt and shame.

Some in the audience surely knew – but most probably did not – that a teenaged Ybanez had strangled his mother in 1998, freeing him from a lifetime of abuse from both parents – and relegating him to a lifetime behind bars.

“I’m better off in prison than I was at home.”

In this rare moment of utter theatrical honesty, the line between life and art dissolved. When an audience member later asked Ybanez if his life in the Sterling Correctional Facility is similarly frightening and violent, he lowered his head and softly said without elaboration, “I’m better off in prison than I was at home.” Those who knew, knew what he meant. Those who did not, did not. Not that it mattered in the context of the performance, which ended in a prolonged and heartfelt standing ovation.

They were standing in appreciation of a performance that was five months and 250 hours in the making. They were standing in thanks for creating both a cultural and life experience that audience member Nancy Portnoy later called “unbelievably powerful, beautiful, truly mind-blowing – and one I will never forget.”

For two hours, these men were not prisoners. They were actors.

Watching the play as an audience member, inmate Andrew Draper said, “was the first time in 20 years that I did not feel like I was in prison.”

During the post-show conversation, the actors acknowledged the audience for their presence and attention.

“Thank you for seeing us,” said Terry W. Mosley Jr., who played Martini, Danny DeVito’s role in the film. “Thank you for seeing us as human.”

Theatre has been taking place in American prisons since at least the 1950s, but there has never before been a program with the aspirations of the DU Prison Arts Initiative, which was launched in 2017 to give Colorado prisoners both a project and a purpose through the empowering potential of creating art. Program Director Dr. Ashley Lauren Hamilton, a professor at DU, says her rapidly expanding program improves prisoners’ quality of life and their sense of self by giving them both a demonstrable goal and an opportunity to see it through. She sees this as an opportunity to make positive changes in these prisoners’ lives, whether they are ever released or not.

“I believe the arts can create a space for incarcerated people to reflect on who they are and where they want to go,” Hamilton said. “I have watched theatre offer a space for these men to become more self-actualized, sharpen their communication skills, become better at conflict resolution and more sociable. Theatre gives them a stronger sense of empathy and a stronger sense of hope. Those are great skills for anyone to have, but they are especially useful for people coming home from prison.”

“I believe the arts can create a space for incarcerated people to reflect on who they are and where they want to go,” Hamilton said. “I have watched theatre offer a space for these men to become more self-actualized, sharpen their communication skills, become better at conflict resolution and more sociable. Theatre gives them a stronger sense of empathy and a stronger sense of hope. Those are great skills for anyone to have, but they are especially useful for people coming home from prison.”

Mosley said it is not an overstatement to call this experience life-changing for him. “In prison, you have no expectations,” he said. “You are set up for loss and disappointment. This, on the other hand, was rehabilitative, it was therapeutic and it was transformative.”

But this remarkable evening did not come easily. Hamilton and her team logged 22,000 miles driving to and from Sterling over five months – nearly the circumference of the Earth.

The choice to present One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Hamilton said, was very intentional.

“Not one ounce of the irony or complexity is lost on me,” she said. When you consider how quickly “the power” diminishes R.P. McMurphy from a small-time gambler into a lobotomized ward of the state, you can understand how these actors might see the leap from petty criminal to death row to be a similarly small step.

“This is the perfect play at the perfect place for the perfect people,” Hamilton said. “Theatre always means more when it means more to the people who are doing it.”

The process began with casting, which played out much as it does for other theatre companies. Prisoners were invited to come in and read selections from the play. Some came out of boredom; some from peer pressure. Many were already taking theatre classes from Hamilton.

From the total prison population of 2,500, Hamilton and co-creator Julie Rada put together an ensemble of actors who remarkably resemble those from the iconic film. Brett Phillips, who is serving 38 years for murder, played R.P. McMurphy, the rebel made famous by Jack Nicholson. Douglas L. Micco, a prisoner with Native American roots who was convicted in 2004 for kidnapping and sexual assault, played Chief Bromden. He’s the gigantic narrator who at one point begs of McMurphy: “Make me big again” – a line that, in this context, carries an eviscerating poignance.

Ybanez, 37, looks uncannily like Brad Dourff, the baby-faced actor who played Billy in the film. But he was not Hamilton’s first choice for the role. He was a replacement for an inmate who got into trouble and was taken out of the project. At the time, Hamilton had no idea Ybanez had been at the center of one of Colorado’s most publicized murder cases. In fact, “I make a practice of not looking them up,” she said of her students. When she found out his story, she made sure Ybanez would be comfortable exploring terrain that so closely mirrored his own experiences. He not only was up for it, Hamilton said, “he was one of the most professional actors I have ever worked with.”

For the public, attending this performance was surely unlike any other theatergoing experience they’ve ever had. Those wanting to attend had to provide personal information for a background check days in advance. They were told to arrive 45 minutes before the 6 p.m. performance to allow time for processing and an escort deep into the facility where Hamilton and her team had converted the prison’s visitor’s room into a makeshift theatre. They were told to leave everything behind in their cars, including cell phones, wallets and even money. They were told to bring nothing, in fact, but their state-issued I.D.

The Sterling Correctional Facility is a heavily protected complex located just east of Sterling, a sleepy farming town of about 13,000. Its massive buildings are wrapped by thousands of yards of barbed fence that from a distance make it look like the world’s largest Slinky toy. As you approach the public entrance, your stomach reflexively tightens up.

“Thank you for seeing us. Thank you for seeing us as human.”

But you are greeted by prison officials with unexpected civility and cheer. You quickly learn that the DU Prison Arts Initiative is a major point of pride for the 750-strong corrections team who work here. “The entire goal here is that we are working toward normalization,” Lt. Shawna Nygaard tells us.

Inmate Torriano Davis played Scanlon, a patient who has fantasies of blowing things up in ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.’ Photo courtesy DU Prison Arts Initiative.

Hamilton is now teaching her curriculum in 10 state prisons, “and that’s 10 chances to make life better,” said inmate Stephen Sparks, the play’s Stage Manager. And that’s just a start.

The University of Denver has just signed a history-making contract with the Colorado Department of Corrections to bring its curriculum into all 18 of the state’s prisons over the next few years, making the DU Prison Arts Initiative the first arts program to be included in the Colorado DOC budget and second in the country behind California.

Its One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest also made history as the first prison play in the country to tour. The state gave its permission for Hamilton to put her entire production on a bus and take it to both the Limon Correctional Facility and the Denver Women’s Correctional Facility. For some of her cast it was their first time off the grounds since the prison opened in 1999.

The next goal, Hamilton said, is to develop up to four fully produced theatre productions every year at prisons across the state. Next up is a staging of A Christmas Carol that will be performed for the public by inmates at the Denver Women’s Correctional Facility in December.

Tonight’s performance of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in Sterling is actually the seventh, after being performed for family members, fellow inmates, DOC officials and members of Governor Jared Polis’ cabinet and executive staff. Tonight’s show is the only one open to the public.

Dr, Asley Hamilton, center, with the cast and crew of ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.’ Photo courtesy DU Prison Arts Initiative.

After a bit of a “prep talk,” where you are given background information and a rundown of the rules for the evening, you settle in for the play, which has been crafted with full theatrical production values. The walls of this barren visitor’s room have been converted into the walls of a psychiatric hospital. There are signs on those walls for the play such as “No Saving Medication” alongside real prison signs such as “Don’t Sit or Stand,” an abrupt reminder that on any normal day here, you had better keep moving.

Ratched’s elevated nurse’s station acts as the play’s center of power. The audience can see through a window to an outside prison courtyard that is incorporated into the play. Portable light trees and essential sound effects heighten the storytelling. Almost all of the props were created inside the prison and all of the costumes were designed by incarcerated Costume Designer Leroy Maestes and borrowed from DU.

The creative process took much longer than a typical theatre performance because Hamilton and her team taught the prisoners every aspect of the theatremaking process – and then empowered them to do it. Rather than hiring multiple award-winning lighting designer Shannon McKinney (DCPA’s Tribes) to create lighting for the show, Hamilton had McKinney come in and work with Rada to mentor prisoners Mannie Legrand and Shakiel Madden-Vaughn on how to do it themselves. Props Designer Coy Dunn gathered everything he would need from within the walls of the prison.

The creative process took much longer than a typical theatre performance because Hamilton and her team taught the prisoners every aspect of the theatremaking process – and then empowered them to do it. Rather than hiring multiple award-winning lighting designer Shannon McKinney (DCPA’s Tribes) to create lighting for the show, Hamilton had McKinney come in and work with Rada to mentor prisoners Mannie Legrand and Shakiel Madden-Vaughn on how to do it themselves. Props Designer Coy Dunn gathered everything he would need from within the walls of the prison.

Behind the audience, a temporary chain-link fence separates theatregoers from a team of inmates who operate all technical elements for the show from a bank of laptop computers. Because everyone learned everything from the ground up, Hamilton and Rada never refer to their team members as prisoners. “They are our incarcerated students,” Hamilton clarifies.

But not all of her actors were inmates. Because One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest features several essential female characters, Hamilton and two of her theatre students from DU joined the cast, including undergraduate Reanna Magruder to play the imperious Nurse Ratched. Imagine being a young woman asked to come into an environment with dozens of men, many convicted of sexual violence against women, to play a character who personifies the dehumanization and emasculation of these men.

“It was emotionally intense for Reanna because she’s a really compassionate and empathetic person,” Hamilton said. “I watched her have to battle her way through this, but she did it.”

Hamilton said she and Rada prepped the female students “intensely” for what they might encounter in the prison. Similarly, Hamilton said, they trained the inmates “intensely” about behaving professionally and respectfully – and what the consequences might be if they crossed any boundaries. Not only for them, but for the program.

“You have to understand, some of these men have been locked up for 30 years,” Hamilton said. “But they know that they are paving the way for all of the people coming up behind them, and that if anything had gone wrong, they would be jeopardizing everything. They took that seriously, and they could not have been more professional.”

As Mosely put it: “Ashley asked us to be the best person we can be in the worst possible place. And we were.”

As the audience is being seated, the actors already have begun silently setting the scene. There is a story written on every face. And the tension is palpable. The nurses are dispensing pills in cups to some patients as others play games or shuffle about in drug-induced stupors. One patient in particular – John T. Saindon as Ruckly – straggles right up to a recoiling man in the front row. “You got my medication?” he says. A few tense minutes into the play, Ruckly blurts out for the first of what will be many times, “(Bleep) ‘em all!” giving the audience its first permission to laugh. Before long, they will be laughing boisterously.

Later, Saindon is asked what it’s like to feel the power of making an audience collectively laugh like that for the first time in his life. “It’s the most amazing, ridiculous high you can ever get,” he says, “and trust me – I’ve done my share of highs.”

These actors are clearly raw, but it’s immediately clear they have fully committed to the task, and there seems to be complete buy-in from the audience. Not a single line is dropped. As a regular theatregoer, you occasionally see novice actors who are cripplingly self-conscious on stage, which only makes the audience uncomfortable in return. But what these actors lack in technique and experience is negated by their complete lack of fear. Then again, when you consider what they go through to get through each day in prison alive, play-acting hardly seems like something to get all that squeamish over.

‘One of the last things I wanted to do before I die was to see you again, and I can’t believe that a play is the reason it’s happening.’

Of all the many moments of connection Hamilton will carry with her from this experience, nothing will match what happened when the bus carrying her cuffed cast and crew pulled up to the Limon Correctional Facility to perform the play there. Prisoners by the dozens gathered in the yard to meet them. Because of frequent transferring, she said, many of the prisoners from Sterling and Limon know each other because they have been incarcerated together before. After the Sterling prisoners got off the bus and were unshackled, she said, the men ran to each other and embraced like family. One man told another through tears: “One of the last things I wanted to do before I die was to see you again, and I can’t believe that a play is the reason it’s happening.”

Nathan Ybanez at age 16.

Then Hamilton noticed another reunion taking place: Nathan Ybanez and Erik Jensen. The two childhood friends had not seen each other since an appeals hearing in 2006. Jensen, who was 17 when Ybanez murdered his mother in 1998, had been tried as an adult and sentenced to life without parole for helping to dispose of her body.

The Ybanez family had moved 30 times before settling in Highlands Ranch when Nathan was 14. At Jensen’s appeal eight years after the murder, Ybanez laid bare a childhood filled with unimaginable physical, mental and sexual abuse. He has since said his ex-soldier father was violent; his mother was unstable and controlling. Both, he said, forced him to engage in sexual activities with them. His back, Nathan said, is covered in disciplinary burns. When Nathan descended into drugs and alcohol, she threatened to send him to a Christian boot camp.

No evidence of his parents’ abuse was ever introduced at Nathan’s trial because his defense was being funded by his father – a clear but never acknowledged conflict of interest.

Nathan and Jensen were both sent away for life. But in recent years, their stories have taken dramatically different turns. The miraculous news for Ybanez is that in 2016, as then-Governor John Hickenlooper was completing his final term, he commuted Ybanez’s life sentence – which essentially means he now will be eligible to be considered for parole for the first time in December 2020.

And in May, Jensen was re-sentenced to life with the possibility of parole after 40 years, which means he still faces another 20 years in jail. The disparity in their fates has touched off major debate about the fickleness of the state’s juvenile sentencing guidelines.

“It’s not fair or just,” Jensen’s father, Curtis, said at the time, “when the guy who did the crime is getting out, and the guy who didn’t has been given 40 to life.”

And now here at the entrance of the Limon Correctional Facility, Ybanez and his co-defendant were seeing each other face-to-face for the first time in 13 years. And get this: It turns out Jensen has been taking Hamilton’s theatre classes in Limon at the same time Ybanez has been taking her classes in Sterling – and she never knew they were connected.

The production of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest that Hamilton and Rada co-created could stand on its own as a small miracle of theatremaking. But to Hamilton, “having a really great play was always secondary to the growth of my students as human beings. What would it matter if they hated each other at the end? The sense of community they had was the most important thing to me.”

Theatre is a collaborative effort that under normal circumstances builds camaraderie and often forges bonds for life. This was no different. “This experience has created a community in this prison population that wasn’t there before,” said Mosley, the inmate who played Martini.

After the performance in Sterling, the audience was invited to mingle with the cast and crew for about half an hour, then were politely told it was time to go home. While they were escorted out to their cars, back inside, the stars of the show they had just seen were being escorted across the prison yard to the 6-foot cells where they would again sleep that night.

But to Terry W. Mosley Jr., it didn’t matter. Not that night. Maybe not ever again.

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theater critics in the U.S. by American Theatre Magazine in 2011. He has since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center’s Senior Arts Journalist.

Dr. Ashley Hamilton, first from the left in the second row from the front, with some of her incarcerated theatre students earlier this year at the Sterling Correctional Facility, many of whom took part in the making of ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.’ Courtesy DU Prison Arts Initiative