DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

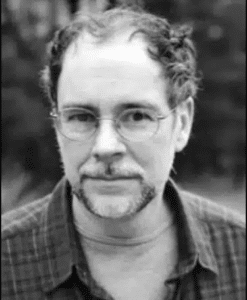

Gregory Maguire, Author of Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

Reprinted by permission of Wicked

What inspired you to write “Wicked”?

Gregory Maguire

Gregory Maguire: I was living in London in the early 1990’s during the start of the Gulf War. I was interested to see how my own blood temperature chilled at reading a headline in the usually cautious British newspaper, the Times of London: “Sadaam Hussein: The New Hitler?” I caught myself ready to have a fully formed political opinion about the Gulf War and the necessity of action against Sadaam Hussein on the basis of how that headline made me feel. The use of the word Hitler – what a word! What it evokes! When a few months later several young schoolboys kidnapped and killed a toddler, the British press paid much attention to the nature of the crime. I became interested in the nature of evil, and whether one really could be born bad. I considered briefly writing a novel about Hitler but discarded the notion due to my general discomfort with the reality of those times. But when I realized that nobody had ever written about the second most evil character in our collective American subconscious, the Wicked Witch of the West, I thought I had experienced a small moment of inspiration. Everybody in America knows who the Wicked Witch of the West is, but nobody really knows anything about her. There is more to her than meets the eye.

How do you feel about Winnie Holzman’s adaptation of your book?

GM: I have been so pleased with the work that Winnie Holzman has done for Wicked. She has taken a novel that is like a symphony in my heart and she has turned it into an opera.

What are some of the similarities between the stage version of Wicked and your novel?

GM: Books are all about secrets. You don’t read a book if you can tell by the flap copy what’s going to happen at the end. And in a way the stage is like that too. The stage is all about what evolves in terms of plot and what evolves in terms of character so I’m not going to give any secrets away. I WILL say that a great deal of what I think of as the dark serious part of the book has been retained. It has been touched with another kind of magic so that it passes unto the eyes in a different way.

What is your reaction to the comparisons many people make between Wicked and The Wizard of Oz?

GM: It’s not a retelling of The Wizard of Oz and it’s not really a prequel. It’s another story of another life. The description of Wicked as a dystopic view of The Wizard of Oz is not, I think, accurate. Closer to the truth is that Wicked focuses attention on some of the perplexing characteristics of the original story: the lack of opposition to the reclusive and manipulative wizard, the absence of interest in or concern for the Witch, the fact that Dorothy, longing for another world in which her troubles might “melt like lemon drops,” is instead exiled in a land of dangerous witches, powerful tyrants, and treacherous landscapes. Truthfully, the magnificent song “Over the Rainbow” might have hung like Marley’s ghost over the entire proceedings at the Gershwin Theater. The fact that its absence is neither an indictment nor a glaring omission is the most fitting testimony to the success of Stephen’s score. When Elphaba sings the bridge in “I’m Not that Girl,” she is offering the more seasoned rebuttal to Dorothy’s lovely fanciful desires. “I’m Not that Girl” isn’t cynical, but it is mature: “Ev’ry so often we long to steal/ To the land of what-might-have-been/ But that doesn’t soften the ache we feel/ When reality sets back in.” This is the sadder-but-wiser girl’s sung response, across 63 or 64 years, to Dorothy’s plaintive request to go abroad and find the grass over there — well, to find it greener.

Can you explain the notion of the “Time Dragon clock” featured so prominently in your book?

GM: The notion of the Time Dragon is twofold. It is patently artificial, like everything having to do with the Wizard’s reign (smoke and mirrors, deceptions and lies, weapons of mass destruction just 45 minutes away, ticktock clockwork, Penn and Teller chicanery). On the other hand, perhaps even a machine has a soul, even a machine can be involved with fate. Elphaba, born in its bowels [in the novel], is in some ways exempt from its gaze, and separated from everyone. Is her life dictated by the events of her birth, or is she alone in Oz, exempt from being seduced by the glamour of the mechanics of power and spectacle? In this, as in so much, I don’t provide an answer: I merely use the mechanics of the metaphor to suggest the question.

How do you think Elphaba’s turning point in the musical, “Defying Gravity,” relates to the one you wrote for her in the book?

GM: The staging of “Defying Gravity” — and by that I mean the song, the way the moment has arisen out of the Winnie Holzman-Stephen Schwartz iteration of the novel’s original plot — makes Elphaba’s transformation much more visible. In the cover art of my novel (and indeed in the graphic art advertising the play), the witch’s hat is over her eyes, and in a sense this is how I drew the character: always a little bit out of view. To close Act One of Wicked, Elphaba’s transformation is, vocally, and theatrically, right in our faces. It is one of the most thrilling moments of the play and rivals the most thrilling act one finales I’ve ever seen, and I am a total fan — though it does take some getting used to. I think, “Elphaba, you’re a little less shy than you used to be when I first knew you!”

DETAILS

Wicked

Jul 24 – Aug 25, 2024 • Buell Theatre

Tickets