DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

This article was published on February 23, 2018

Video by DCPA Video Producer David Lenk and Senior Arts Journalist John Moore.

In this daily four-part series for the DCPA NewsCenter, we introduce you to the plays and playwrights featured at the Denver Center’s 2018 Colorado New Play Summit. Over the past 13 years, 29 plays introduced at the Summit have gone to be premiered on the DCPA Theatre Company mainstage season. Today: Barbara Seyda, author of Celia, A Slave.

Barbara Seyda attended a backyard barbecue in Arizona eight years ago that not only changed the course of her life, it raised the voices of the dead.

Seyda met a historian and scholar at the University of Arizona named John Wess Grant. “And instead of making cocktail party chatter, he began telling me stories of freed and enslaved women of color from the 19th century — for three hours,” she said. “I went home that night and had a dream, which I think was a subconscious affirmation of the play.”

‘Celia, A Slave,’ rehearsal photo by Adams Viscom.

The play is Celia, A Slave, which recalls a 19-year-old African-American slave who was convicted of killing her master in 1855 and hanged. It is one of four featured plays at the 2018 Colorado New Play Summit that begins today. It was the first play written by Seyda, who was an Arizona-based writer, editor, photographer and designer until the voices of history spoke to her.

“I think about that moment a lot because I never studied slave litigation, and I wouldn’t have discovered this trial on my own,” she said. “So that was definitely an alchemic moment.”

Seyda does not know why she had that life-changing dream that night. But she accepted the muse freely.

“I think stories arrive on their own, like love and forgiveness,” she said, “and then we have to be brave and surrender to them. I also think writing is an irrational act. I think a lot of writing comes from the subconscious. It comes from ancestral spirits. It comes from our bodies and the silences that we hold within our families or within our communities and cultures.”

Seyda pays attention to her dreams. “And that was a significant dream,” she said.

Photo by John Moore.

Here’s more of our conversation with Seyda:

John Moore: What happens in your play?

Barbara Seyda: My play is based Celia’s trial. It’s told from the perspective of 24 characters, so it’s kaleidoscopic in structure and fragmented. It deals with systemic racism, slave litigation, rape and the execution of a juvenile.

John Moore: Tell us about your journey as a playwright.

Barbara Seyda: I don’t have an MFA from Yale in playwriting. I’ve never studied writing or theater. Celia, A Slave is my debut play. But I’ve been working backstage for 38 years, so that’s been my drama school. I learned about theater working backstage, on the loading docks, in the pipe tunnels, the badly lit stairwells and the dressing rooms. After my dream, I began writing Celia as a screenplay. During that process, I saw Katori Hall‘s play The Mountaintop, directed by Lou Bellamy (DCPA Theatre Company’s Fences) at the Arizona Theatre Company, and it was astounding and inspiring. I went straight home and reframed the play for stage because I was just so invigorated by what Katori Hall did. She took a historical moment — the eve of Martin Luther King‘s assassination — and created this amazing, expansive, panoramic platform to explore: Two people are meeting at a hotel room: King and Camae, the maid, in a motel room. That’s the entire play. The other play I’ve always loved is Fires in the Mirror by Anna Deavere Smith in 1991. She wrote in response to an incident in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, where a Hasidic rabbi’s motorcade went up on a sidewalk and hit a Haitian boy who died, and riots ensued. And Anna Deavere Smith interviewed all these folks and there are 31 voices in that play. It’s a brilliant intersection of journalism and performance and public ritual. And I really studied that piece structurally when I was writing Celia, A Slave.

John Moore: But Anna Deavere Smith had the benefit of being able to go back and interview the actual participants. You’re exploring something happened in 1855. So how did you approach your research when there’s nobody to interview?

Barbara Seyda: I did a lot of archival research. I looked at the actual trial transcripts and court records. I looked at genealogical records and diaries and letters and legal papers. But I was also hearing voices at night. So I kept a notebook by the bed and I recorded the voices. I didn’t know who was speaking or in what context. I just listened. I also scheduled interviews with midwives and hog farmers and death-penalty attorneys and the descendants of slaves and the descendants of slave owners, and basically anyone I could find who grew up in Missouri. And along with all of that, I started doing random street interviews with people I didn’t know and then braided all of that material into the text.

John Moore: What was driving you to wrote this story? Was it anger when you heard about what happened to Celia? A need to put this into the historical record?

Barbara Seyda: It wasn’t anger, but anger can be a catalyst and a motivating force. As a journalist, I was always interested in foregrounding the voices of those silenced by the mainstream. So this felt very much a continuation of what I’ve always done, except that I was doing it for stage instead of for the press.

John Moore: So what are we actually seeing in your play? Is it a courtroom trial?

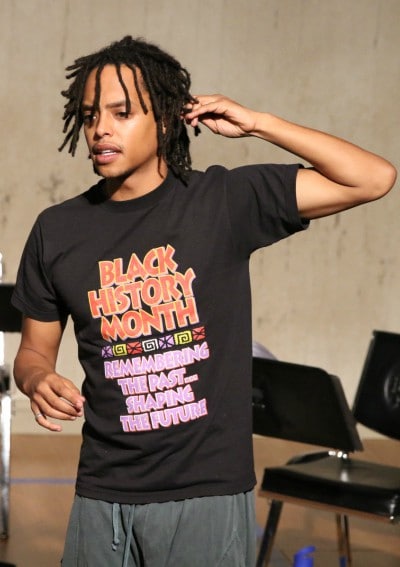

‘Celia, A Slave’ cast member Jacob Gibson. Photo by John Moore.

Barbara Seyda: It’s not a courtroom drama. It’s a collision of voices of the dead. At one point in my writing I thought, ‘If I could somehow just gather all these characters in a room and interview them, this would make my job a lot easier.’ So I envisioned myself as a journalist interviewing the dead. The play kind of takes you through that process and that journey.

John Moore: So why is now perhaps the right time for us to be looking back at what happened in 1855 to better understand better what’s going on in America in 2018?

Barbara Seyda: When I initially started working on the play, I asked myself, ‘Who is going to be interested in this obscure female slave trial from 1855 in pre-Civil War Missouri?’ I really didn’t know if it would resonate with anyone. But now I think that the racists’ consciousness that existed in 1855, and the rape culture that existed then is what created the foundation for American capitalism that continues today. We see it manifesting all the time. We see it manifesting in the White House.

John Moore: You’ve already been through the first weekend of the Summit, so can you talk bit about what you learned in the first week and the first public reading?

Barbara Seyda: The first week was amazing and intense and horrifying because I came with an original script and I didn’t really know what was going to happen with that. And then (DCPA Theatre Company Associate Artistic Director) Nataki Garrett — my brilliant, genius, iconoclast director — she jackhammered the script, and we blew it up into 20,000 moving pieces. And just last weekend, I wrote six new scenes. So we had the original script, we had these fragments and then we had the new material. So the artistic team started to panic a bit. That’s when I realized that the writer’s like a quarterback. You’re calling the plays and everyone’s looking to you. And the writer doesn’t always know the answer. And so I said, ‘Have faith in me and have faith in the play and in this process.’ So we kind of moved through a slot canyon at night and through a 30-mile boulder field, and now we’re coming out on the other end of it. And basically, we’ve given birth to a whole new script.

John Moore: And just to clarify the history of this work: You won the national Yale Drama Prize for this play in 2015. So how is it still considered a new play?

‘Celia, A Slave’ cast member Erin Willis. Photo by John Moore.

Barbara Seyda: We had a reading at Lincoln Center in New York, directed by Nigel Smith. And then the Rogue Theater in Tucson opened their season with it in September. But yes, the play continues to go through a transformation — and it’s gone through the most radical transformation here in Denver.

John Moore: Is that transformation essentially taking a script that was primarily direct address and making it more of a tapestry?

Barbara Seyda: I think it’s becoming more of a tapestry play but I don’t know because I don’t have a cohesive vision of the new whole yet. I mean, there are sections that feel like stained glass to me. There are sections that feel like broken nails. There are pieces that feel highly orchestrated, tight, and precise. There are other sections that still feel kind of organic. And maybe there are still some potholes.

John Moore: I know you are right in the middle of it, but how do you feel now that the Colorado New Play Summit exists and that this two-week development process is available to you?

Barbara Seyda: I am so grateful for this Summit. I mean, it’s pretty rigorous and challenging and intense. But because of all that intensity and rigor, something amazing, I think, is going to emerge.

John Moore: Tell us about this particular collection of actors you’ve been given to work with here in Denver.

‘Celia, A Slave’ cast member Cajardo Lindsey. Photo by John Moore.

Barbara Seyda: I will just say I would crawl miles on my knees to see these actors perform. They are astounding. I’m humbled by their talent, by their ability, by the gifts that they bring to the table and to the stage. For example, Jingo is the hog farmer who starts the play. And he now has a significantly expanded role in the story that didn’t exist before I arrived — and that’s because of the actor who’s playing him, Cajardo Lindsey. There’s something about him, about his presence, just being able to conjure and express this character. It just seemed to require and demand that I write more for him.

John Moore: And what about your dramaturg?

Barbara Seyda: Sydne Mahone is legendary. She has been my friend for 38 years, and a huge inspiration through my whole life. We met at Rutgers and after she graduated, she became the Literary Director and dramaturg at Crossroads Theatre Company in New Jersey, which was one of the pioneering African-American theatre companies in the U.S. She also created the annual Genesis playwriting festival. Folks like George C. Wolfe and Anna Deavere Smith and Suzan-Lori Parks and Robbie McCauley were all unknown until she brought them to Crossroads and produced their work. Then they went to New York and became mega superstars. She also was the editor of Moon Marked and Touched by Sun, which was the first anthology of African-American women playwrights. And so to have Sydne next to me on one side and Nataki on the other? Wow, what a team.

John Moore: And finally: What do you think Celia would say if she knew this play existed?

Barbara Seyda: God, what would Celia say? Well, she’s finally had the opportunity to tell her own story.

‘Celia, A Slave’ cast members Tihun Hann, Celeste M. Cooper and Owen Zitek. Photo by John Moore for the DCPA NewsCenter.

Celia, A Slave: Cast list

Written by Barbara Seyda

Directed by Nataki Garrett

Dramaturgy by Sydne Mahone

Stage Manager: Heidi Echtenkamp

Stage Management Apprentice: Molly Becerra

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!