DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

In 1865 Texas, chaos prevailed. The Civil War ended on April 9 of that year, but the news spread sporadically and in much of the state, enslaved Black people didn’t learn they were free until June 19, when Union Gen. Gordon Granger proclaimed it upon landing in Galveston. Although Black people were legally free, they had no land, seldom had any education, and encountered hordes of angry white Texans looking to exploit, imprison, or kill them. Nearly 400 freed Black people were recorded as being murdered by white people between 1865 and 1868.

In 1865 Texas, chaos prevailed. The Civil War ended on April 9 of that year, but the news spread sporadically and in much of the state, enslaved Black people didn’t learn they were free until June 19, when Union Gen. Gordon Granger proclaimed it upon landing in Galveston. Although Black people were legally free, they had no land, seldom had any education, and encountered hordes of angry white Texans looking to exploit, imprison, or kill them. Nearly 400 freed Black people were recorded as being murdered by white people between 1865 and 1868.

Federal troops arrived in Texas that spring to enforce U.S. loyalty among former Confederates and, secondarily, to protect newly free Black people. But within a year, their forces were reduced from 51,000 to 3,000, with most of those sent to the western frontier. Vast swaths of eastern Texas – where the majority of plantations had been – were left unpoliced by the federal government. The white populace was generally hostile. One-fourth of white families in Texas previously had enslaved people, and three-fourths of Texas voters had supported secession from the Union.

That year, the federal government established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. Its stated intention was to help formerly enslaved people transition to freedom safely. In reality, they were frequently forced to return to plantations as paid laborers, or they were offered work and only compensated with a share of the crops they produced on the land. The latter was the origin of sharecropping. Freed Black people in Texas were not permitted to buy property at this time; sharecropping was a de facto means of keeping formerly enslaved persons indentured indefinitely.

Texas also passed statutes to allow landowners and authorities to coerce free labor with the threat of forced labor. Minors could be apprenticed with parental permission or court order, with their white “overseers” permitted to use corporal punishment and pursue runaways.

Many of these statutes, known as the Black Codes, were abolished by 1867. However, despite the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870, Black voters continued to be suppressed by racially targeted rules regarding poll taxes, literacy requirements, and “grandfather” clauses. It was not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and its enforcement, that Black Americans had full voting rights; today, strategies have been revived in Texas to diminish the impact of Black votes.

In the words of freedman Houston Hartsfield Holloway: “We colored people did not know how to be free and the white people did not know how to have a free colored person about them.”

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere. “

— General Order No. 3, issued by Union Gen. Gordon Granger on June 19, 1865, at Galveston, Texas.

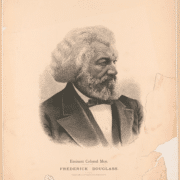

In 1852, Frederick Douglass addressed white abolitionists with his speech, “What to a slave is the Fourth of July?” Thirteen years later, Major General Gordon Granger ordered the final enforcement of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in Texas, where most Black residents had endured an extra two and half years of slavery. The day was June 19, honored as Juneteenth, and widely known as “America’s Second Independence Day.”

In 1852, Frederick Douglass addressed white abolitionists with his speech, “What to a slave is the Fourth of July?” Thirteen years later, Major General Gordon Granger ordered the final enforcement of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in Texas, where most Black residents had endured an extra two and half years of slavery. The day was June 19, honored as Juneteenth, and widely known as “America’s Second Independence Day.”

Other states around the country have had their own emancipation commemorations, including Mississippi (May 8), Florida (May 20), Kentucky (Aug. 8), and Maryland (Nov. 1). Beginning in the 1920s with the Great Migration, Black residents of Texas spread across the nation, bringing with them their Juneteenth celebrations.

“Whites had much more reason to see the Declaration of Independence as the fulfillment of something: namely, of their desire to create a nation over which they exercised control,” wrote Annette Gordon Reed in The New Yorker in 2020. “From the country’s earliest days, whites in the South, in particular, saw their freedom as inextricably linked to their power over African-Americans, power that they maintained, through legal and extra-legal means, even after slavery’s end…. For Black people, the Declaration carried a promise not yet fulfilled. It was in this sense that Juneteenth and the Fourth of July were, in fact, related.”

SOURCES:

National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/historical-legacy-juneteenth and https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/what-juneteenth

“Growing Up with Juneteenth,” Annette Gordon-Reed, The New Yorker, June 19, 2020

“What Is Juneteenth?” Henry Louis Gates Jr., PBS.org (republished from The Root)

Digital History: Reconstruction in Texas

“Civil War and Reconstruction,” by Katie Whitehurst for Texas PBS

Texas State Historical Association

“Reconstruction and its Aftermath,” Library of Congress