DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

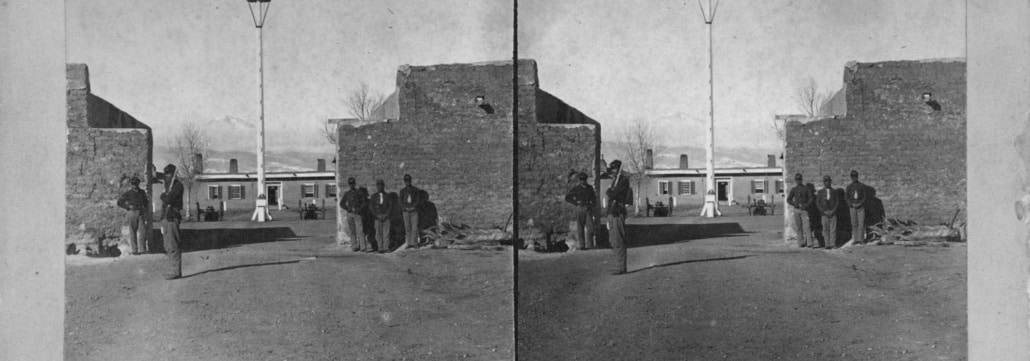

Buffalo Soldiers. Photo courtesy History Colorado

Although not eligible to enlist in the Union army prior to President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Black soldiers numbered around 185,000 — about 10% of Union forces — by the time the Confederates were defeated in April, 1865. Their duties were largely separate but not equal: White soldiers were paid almost twice as much per month and Black soldiers were largely relegated to non-combat service roles. In 1866, Congress authorized the creation of six regiments of Black troops (commanded by white officers): the 9th and 10th Cavalries and the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantries. (The four infantry units were soon consolidated into two — the 24th and 25th.)

Southern civilians refused to accept the authority of Black soldiers, so after the war ended more than 10,000 men still serving three-year enlistments were deployed west of the Mississippi River, mostly in the state of Texas and what are now Colorado and New Mexico. Their mission? To create and protect permanent settlements in the West and to battle the Plains Indians who were fighting to retain their ancestral lands. The Native Americans referred to these enlisted troops as “buffalo soldiers” feeling that the soldiers’ dark hair, fierceness and tenacity resembled the powerful bison that then dominated the Great Plains.

Over the next 30 years, the Buffalo Soldiers would establish forts, protect mail and stagecoach routes along the Santa Fe Trail, and engage in more than 150 fierce battles against Native American warriors. Playing a part in the captures of both Apache Chief Geronimo and bank robber Billy the Kid, Buffalo Soldiers also reserved 17 Medals of Honor for valor in combat.

In southern Colorado, the soldiers were garrisoned at Fort Garland, Fort Lyons and Fort Lewis. On the opposite end of the state, members of the regiments participated in the Battle of Milk Creek in northwest Colorado and the Battle of Beecher Island. They did not take part in the horrific Sand Creek Massacre, but were instrumental in subjugating the Ute, Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples. After the Indian Wars, the all-Black units served with distinction across the globe (including in Cuba where they saved Teddy Roosevelt’s famed “Rough Riders”) until 1948, when President Truman abolished segregation in the military with Executive Order 9981.

To learn more about the legacy of the Buffalo Soldiers, visit the buffalo soldiers: reVision exhibit, which just opened at History Colorado’s Fort Garland Museum & Cultural Center. Or tune into the hour-long documentary “Buffalo Soldiers: Fighting on Two Fronts,” currently airing on Rocky Mountain PBS.