DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

In 1969, as in so much of the country, residents of the largely Latino neighborhood of Auraria were in turmoil.

Many young Latinos were being shipped off to Vietnam. Civil rights movements were in full swing, including the Chicano Movement led in Denver by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, founder of the Crusade for Justice. In 1969, the organization supported students in their protest of a racist teacher at West High, a walkout that resulted in the teargassing of Denver’s Westside by police for three days afterward.

Many young Latinos were being shipped off to Vietnam. Civil rights movements were in full swing, including the Chicano Movement led in Denver by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, founder of the Crusade for Justice. In 1969, the organization supported students in their protest of a racist teacher at West High, a walkout that resulted in the teargassing of Denver’s Westside by police for three days afterward.

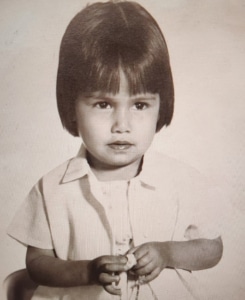

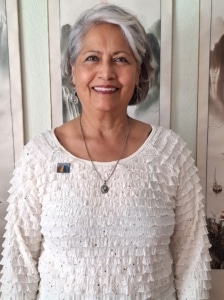

Also that year, parents of Denver schoolchildren, including Sheila Perez Kindle’s mother, filed suit against the Denver Public Schools alleging segregation practices. The decision on the case, written by Justice William J. Brennan in 1973, the year the last Aurarian departed the neighborhood, was key in defining de facto segregation.

To top it off, in 1969, Denver voters passed a bond issue to demolish the community of Auraria to make way for a college campus.

When the bond issue passed, it was a devastation to so many elders in the community. They didn’t know where they would go. Redlining was going on in the city. They didn’t where they could go.

The community had only three months to fight the proposal.

“In a book written about Auraria, the author said the community was somnolent. We were never somnolent. We fought,” she said. “The Westside Coalition was formed and fought hard against [the Denver Urban Renewal Authority], who made promises, one of which was the [Displaced Aurarian] Scholarship, but also that we’d have access to the library and the gym. That they’d help with moving costs. They gave some families $1,500, which didn’t go very far. Renters got no money.”

For residents including Perez Kindle and her family, it was traumatic to be forced to leave their homes in that manner. People dispersed. Relationships were severed.

Perez Kindle was baptized at St. Cajetan’s Catholic Church. She made her First Communion at nearby St. Elizabeth’s Church, which was built in 1898 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1969, and was given her first babysitting job there. The progressive parish offered classes for English-language learners, and Perez Kindle took care of their kids. “A nun there taught me to play tennis in her full habit. I was a tennis instructor for many years after that. She was so generous and made me feel like I was destined to be somebody. I wish I could see her and thank her.”

Perez Kindle was baptized at St. Cajetan’s Catholic Church. She made her First Communion at nearby St. Elizabeth’s Church, which was built in 1898 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1969, and was given her first babysitting job there. The progressive parish offered classes for English-language learners, and Perez Kindle took care of their kids. “A nun there taught me to play tennis in her full habit. I was a tennis instructor for many years after that. She was so generous and made me feel like I was destined to be somebody. I wish I could see her and thank her.”

Meanwhile, a counselor at West High told Perez Kindle, “I don’t think you’re college material.”

Perez Kindle tried repeatedly for the Displaced Aurarian Scholarship. “Every time, they denied there was such a promise made,” she said. “But we’re resilient. Displaced but not erased. We were there then and we’re still fighting now. It wasn’t until we were forced out that we left.”

Perez Kindle is part of the Auraria Historical Advocacy Council, which is working on the construction of a peace and healing garden. “It will be a good place to reminisce. We hope to bring in community that are still here; so many have passed or aged so much a visit might not be possible. We want them to come back and feel honored. We want them to know they are not forgotten.”

The AHAC will also be moving into office space on the campus for the first time and striving to be a resource for the scholarship recipients. “We really want to know why some students weren’t continuing and try to find a ton of resources for them, counseling or whatnot. There are so many potential obstacles. Cost, daycare, transportation. We want to help them get through.”

Like Frances Torres, Perez Kindle wants everyone eligible to receive the scholarship, and to see the stories of the families who endured trauma that was never recognized be memorialized.

Like Frances Torres, Perez Kindle wants everyone eligible to receive the scholarship, and to see the stories of the families who endured trauma that was never recognized be memorialized.

Through efforts like An Auraria Parable, “Our stories are being told. People are finally understanding a little bit of what happened,” she said. “Until all the people know, until that site is recognized as the Old Westside, we have to be certain our strength will be shown. We have