DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

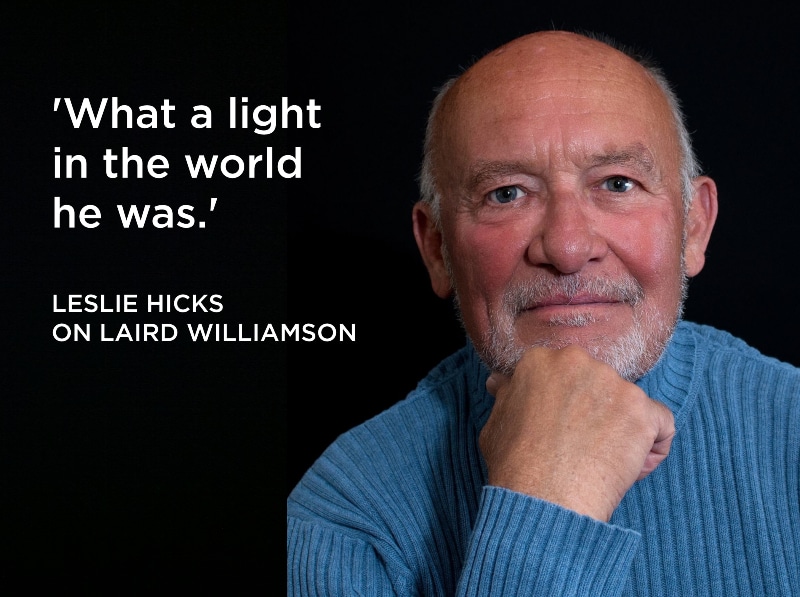

Photo by David Michael.

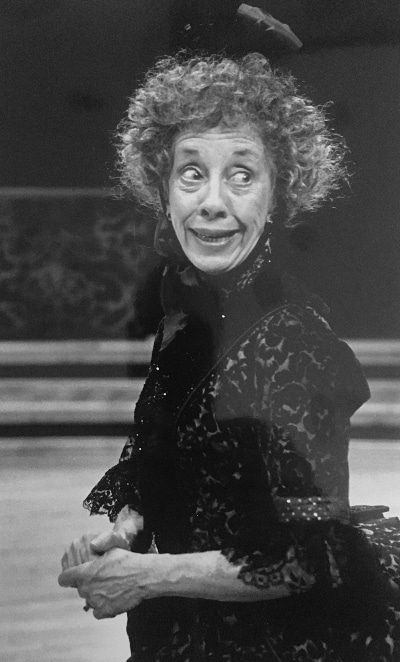

As he prepared to open the DCPA Theatre Company’s 1988 production of The Matchmaker, Laird Williamson gathered his actors and seduced them with a rallying cry that fairly summed up his approach to five decades as a director – and 82 years of life. Like a coach to his players before a big game, Williamson assured them: “Beauty is our weapon!”

Ann Guilbert as Dolly Levi in ‘The Matchmaker.’ Photo by Ted Trainor.

Williamson’s goal was to make everything he staged beautiful.

“Actors worshipped Laird,” said 21-year Artistic Director Donovan Marley. Williamson was considered “an actor’s director” not only for his gentle, mind-expanding approach to storytelling, he added, “but because he had a simply spectacular visual sense.”

Actors in Denver and around the country were sharing manifold examples of that singular visual sense on Wednesday as news spread that Williamson, a seminal figure in the history of the DCPA Theatre Company as well as the Pacific Conservatory for the Performing Arts, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, The Old Globe and more, had died of complications from liver disease in Lake Forest Park, Washington.

There was his production of Two Gentlemen of Verona where he made it rain glitter – for a staging Williamson presented as a musical with just four actors who switched roles every night. In A Christmas Carol, he had the surviving Cratchit children carry a long piece of china silk to represent the death of Tiny Tim.

In Life is a Dream, veteran actor Leslie O’Carroll’s character died from a gut-eviscerating gunshot, which Williamson made lovely by having the actor pull red feathers from her cummerbund and toss them into the air to depict blood floating softly across the sky. “It was the most beautiful death ever,” O’Carroll said.

“Laird was fearless, and he would try anything. He was the most creative person I ever knew.”

On Facebook, actor Leslie Hicks called Williamson “a true force of nature who brought wondrous productions to ravishing life.”

‘His talent and vision certainly compare with anybody who is creating on Broadway today.’ – Jacqueline Antaramian

Williamson directed more than 40 plays for the DCPA Theatre Company over a 25-year span from 1981-2005, including 14 seasonal stagings of his own adaptation of A Christmas Carol. It was a remarkable tradition that was seen by an estimated combined Denver Center audience of 350,000.

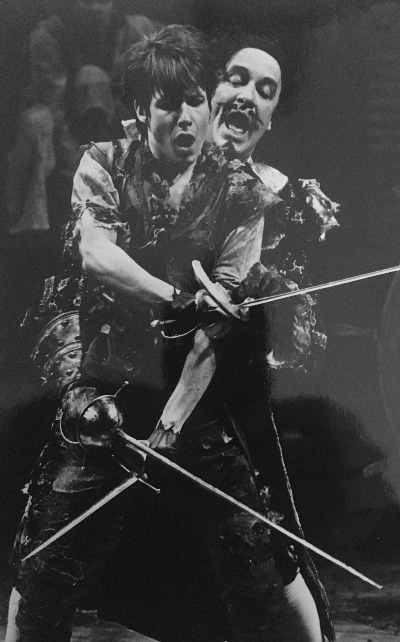

John Cameron Mitchell and Laird Williamson in the DCPA Theatre Company’s ‘Peter Pan.’

Williamson was also a playwright, scenic designer and occasional actor – including a notable stint as Captain Hook opposite John Cameron Mitchell’s Peter Pan in 1989, just a few years before Mitchell went on to fame as his alter ego, Hedwig. Over the years, Williamson’s acting canon spanned everything from Hook to Iago to Claudius. He also found his way to the small screen, with spots on both Mannix and Mission Impossible.

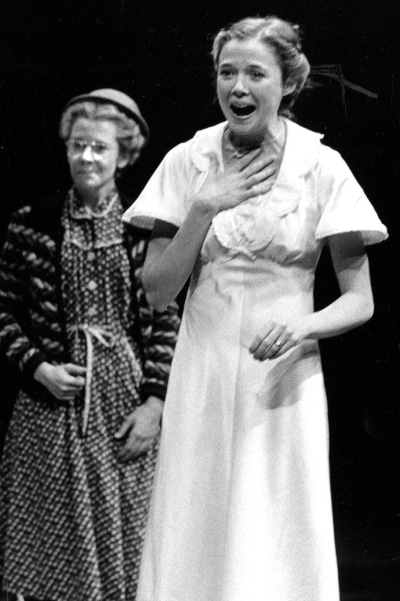

Academy Award-winning actor Annette Bening’s memories of her time with the DCPA Theatre Company are steeped in fondness for Williamson, who cast her to play the Virgin Mary in his own play, 1985’s Christmas Miracles. But their connection already went back decades. The first play Bening ever saw as a girl was at The Old Globe in her hometown of San Diego, and it was directed by Williamson. “I was just knocked out,” Bening said. “I fell in love with the whole life and energy surrounding the theater. Laird is the reason I took up acting as a teenager.”

The American theatre landscape is filled with similar stories today about the influence of Williamson, a gentle man who is being remembered as a giant, open beating, creative heartbeat that will beat on in their memories long after his death.

‘Laird is the reason I took up acting as a teenager.’ – Annette Bening

“Laird was seminal in me taking my understanding and respect for the nobility of theatre to another level,” said Jacqueline Antaramian, who appeared in more than 20 plays directed Williamson in Denver and across the country. “He’s an American treasure who wasn’t well-known in New York City. But his talent and vision certainly compare with anybody who is creating on Broadway today.”

Annette Bening in the DCPA Theatre Company’s ‘Christmas Miracles.’

Antaramian said Williamson’s understanding of the psychological beauty of storytelling was “pure magic.” In a 2000 interview with American Theatre magazine, former Oregon Shakespeare Festival Artistic Director Libby Appel described Williamson’s talent as “a special ability to create the world in which the play operates, a world that dazzles the audience and tells the story in a unique and imaginative way.”

But Antaramian will always remember him for his gentle approach with actors. “Everything he did was just a beautiful gesture of love and trust,” she said. For example, when she was a young actor playing Regina in The Little Foxes at the American Conservatory Theatre in San Francisco, Williamson noticed that employing a Southern accent tended to make Antaramian’s voice go higher. But instead of just telling her, “Go low!” he pulled Antaramian aside and said to her: “Here’s something you might want to consider: Where does her voice come from?”

“He was trying to get me to come at the character from a deeper place in my body,” she said. “Before long, my voice was deeper than it had ever been before, and that shifted my whole perspective on the character. But he asked me in a way that allowed me to discover that for myself.”

Williamson was born on December 13, 1937, in Chicago, to Walter and Florence Williamson. He received his Bachelor of Science degree in Speech from Northwestern University in 1960 and a Master of Fine Arts in Drama from the University Texas in 1965.

In a 2000 interview, Williamson said it was the childhood combination of radio and live theatre that launched him on what he called a lifetime flight of fancy.

Laird Williamson at play.

“I grew up listening to the radio, so whenever I read a play now, I hear it – and when I hear it, I see it,” Williamson told American Theatre magazine. “I also grew up going to the Goodman Theatre, so the two forms kind of welded together for me.”

In 1968, Marley brought Williamson into his artistic family at the PCPA, which Marley founded in 1964 in Santa Maria, Calif. Williamson first directed for the DCPA Theatre Company in 1980. Arthur Kopit’s stroke drama, Wings, was just the 11th production in the company’s history.

In 1983, when Marley was named the new Artistic Director for the DCPA Theatre Company, Williamson was among a sprawling band of 66 company members who moved with Marley to live and work in Denver full-time. The gypsies included directors Randal Myler, Anthony Powell, Nagle Jackson and Bruce Sevy; longtime costume and set designer Andrew Yelusich; and dozens of actors including Antaramian, Kathleen M. Brady, Carol Halstead and many more.

In a 2005 interview, Williamson said: “A lot of us were very, very young when we met Donovan, and he was the guy who urged us to turn our dream of a life in the theater into a reality.”

Jamie Horton in ‘John Brown’s Body.’

Over the years, Williamson took on an astonishing array of theatrical subjects, although he had a special love for plays with magic and wonder – particularly (and rather unusually) Shakespeare’s more problematic plays, such as Pericles and The Winter’s Tale. On the flip side, he helmed a wrenchingly relevant Denver premiere of Moises Kaufman’s Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde, a staging so successful the company remounted it the following year.

“Laird had so much integrity and such a genuine care for humanity that whatever he worked on had to truly matter to him,” said Halstead. “Any play he did had to have some kind of a greater purpose. That is what really turned him on.”

Marley cites among Williamson’s greatest accomplishments Pericles, St. Joan, Life is a Dream and his own 2004 adaptation of John Brown’s Body, cited by The Denver Post as “without question one of the monumental physical achievements in the company’s history.” Here is an excerpt from that review, which was based on Stephen Vincent Benét’s epic 1928 poem about an abolitionist who changed the course of American history in 1859 when he led a ragtag band of 21 men in an ill-fated attack on a federal arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, Va. Many historians consider that to be the opening salvo of the bloodiest war in U.S. history:

“Like Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s unflinching final drive to doom, innovative director Laird Williamson relentlessly approaches this deeply personal spectacle with concepts so surprising and unorthodox, he almost willfully leaves his audiences both mesmerized and as emotionally ambivalent as a broken soldier returning from war. Williamson brings Benet’s opus to vivid, percussive and lyrical life by employing every conceivable theatrical device – and some never thought of before. Through constantly transforming styles and forms, what Williamson conveys is the metamorphosis of a nation from blind naiveté to one shaken to its ideological core.”

Williamson’s depiction of a conflict of two civilizations bound together in a trap of their own making sounded very much like it could have been describing America in either 1859 or 2006 … or 2020. “To this day, the stinging question of the Civil War haunts and resonates,” Williamson said at the time. “How is it possible for a republic for so long to abdicate its enlightened ideals and ignore its ethical responsibilities to its fellow human beings that the use of violence should become inevitable, and war the final arbiter of its political affairs?”

Allison Watrous, a graduate of the Denver Center’s National Theatre Conservatory and now its Executive Director of Education and Community Engagement, was one of 20 actors in that play. She called Williamson one of the most inspiring directors she’s ever worked with. “His visual storytelling and imaginative staging was breathtaking,” she said. “It was a gift to be in one of his plays.”

But of all his stage accomplishments, Williamson’s lasting legacy no doubt begins with his ongoing love affair with A Christmas Carol, which he adapted with Dennis Powers and now has been performed around the world for 40 years. “He never, ever got tired of that thing,” Halstead said with a laugh.

One of Laird Williamson’s 14 seasonal stagings of ‘A Christmas Carol’

Even after hundreds of performances, “A Christmas Carol can be a life-changing experience, if people are open to it,” said Williamson, who saw the story of Scrooge’s redemption as indelibly tied to the winter solstice and its promise of new beginnings, longer days and more sunlight. That, said Halstead, is part of his birthright. Williamson, it turns out, was born on December 13, which is St. Lucy’s Day. “She’s the bringer of the light,” Halstead said.

Williamson considered the winter solstice to be the most important holiday of the year, and he was known for hosting a party every December 21, which always fell near the end of each seasonal run of A Christmas Carol.

“Laird was a sensualist who loved to eat and drink and laugh and cook and have dinner parties,” Halstead said. “So on every December 21st, we would all gather at someone’s house, and Laird would ask everyone to bring readings about welcoming back the positive light of the world.”

‘Laird was all heart and love.’ – Gabriella Cavallero

Gabriella Cavallero, who performed in more than a dozen productions of Williamson’s A Christmas Carol stagings as Mrs. Cratchit and The Ghost of Christmas Past, said Williamson made cast and creatives cry at every single first rehearsal with his inspiring pep talks. “We would enter the rehearsal room and see intricate collages and signs he made for each new year with messages like ‘Banish Fear,’ ” she said. “For Laird, our mission as artists in this and every show was to be messengers of beauty and love and light so that we might help break open some hearts in our audiences. He was relentlessly committed to this mission.”

In 2005, the DCPA Theatre Company moved its A Christmas Carol tradition forward by switching to an adaptation written by Richard Hellesen and David de Berry. That was bittersweet for Williamson, but he called the change “a welcome reminder of the transitory nature of everything.”

Williamson is survived by an older brother, along with nieces and nephews. But his heart family, Halstead said, is much, much larger than that.

“So many of my dearest friends I only have because Laird brought us together,” Halstead said. “Laird gathered all these great souls to go on these theatrical and life adventures together. He was the connective tissue. So while he didn’t have a big family, we are all one big family – because of him.”

Jamie Horton, center, officiated the wedding of Douglas Harmsen and Stephanie Cozart on The Space Theatre in 2006.

Take, for example, longtime DCPA actors Douglas Harmsen and Stephanie Cozart, who were married in The Space Theatre in 2006. Both credit Williamson for bringing them together when he cast them both in his 1996 production of Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia – a play that toys with the notion that love and science are unpredictable and equally powerful forces.

“We call him our fairy godfather because he brought us together,” said Cozart.

In rehearsal, Williamson introduced the word “allurement” as his catchword for the play. “It means a love of life and a fascination with the universe,” said Harmsen. “The same force that binds particles and holds the planets together also applies to human beings.”

The point being, Cozart added, “that you have no choice in the matter.”

Not after they met Williamson, a man Marley sums up as his brother – a man “who spent a spectacular life as an artist, which is an incredible legacy for anyone.”

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theatre critics in the U.S. by American Theatre Magazine. He has since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center’s Senior Arts Journalist. He was the theatre critic at The Denver Post and was the author of the ‘John Brown’s Body’ review excerpted above.

As a director:

*New-Play Readings

As a Scenic Designer:

As an Actor:

As a Playwright: