DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

The late Robert Garner, who built Denver into one of the premiere Broadway touring spots in the country, credited Bill McHale for creating a live theatre audience in the metro area while he and Donald Seawell were getting the Denver Center for the Performing Arts off the ground.

Arlene and Bill McHale were married for 65 years. Photo by John Moore.

McHale produced nearly 200 shows seen by 4.6 million playgoers over 30 years at the beloved old musical barn known as the Country Dinner Playhouse at Interstate 25 and Arapahoe Road in southeast Denver.

“Robert once told me that if it weren’t for the Country Dinner Playhouse, he would not have been as successful as he was at getting people to come to the Denver Center because we had popularized legitimate theatre in Denver,” McHale once said. “We brought in people who had never been to the theatre before, and we turned them into theatre lovers for life.”

McHale, both a character and a man of character, died Tuesday of complications from Alzheimer’s disease. He was 86.

“The man had a heart as big as his voice,” said his daughter, Maureen McHale Dailey.

McHale was known as Cowboy Bill to some because of how he dressed. To others he was Papa Bill, because he was a father figure to hundreds of Colorado theatre artists whose professional careers he helped launch. The list includes nationally known stars such as Beth Malone, Amy Adams, Annaleigh Ashford, Melissa Benoist, Andy Kelso, Morgan Fairchild, Mara Davi, Rachel deBenedet, Rebecca Eichenberger, Patty Goble, Ted Shackelford, Lee Horsley, Lise Simms and Terry Rhoads.

Among the long list of local actors and designers who worked for McHale are Jan and Marcus Waterman, Michael J. Duran, Paul and Penny Dwyer; Deborah Persoff, Alann Worley, Michael Gold, Randy St. Pierre, Brian Smith, Sue Leiser, Jeff Hovorka, Jan Giese, Rob Costigan, Brian Mallgrave, Thaddeus Valdez, Markus Warren, Bob Hoppe, Maggie Lamb and the apple of his eye, his daughter Maureen.

“I cannot overstate Bill McHale’s influence on my career,” said deBenedet, who has gone on to perform in six Broadway shows including Nine and The Addams Family.

He was, in the words of the Tony Award-nominated actor Beth Malone, a giant … in every way.

Bill McHale with the cast of ‘South Pacific,’ including Beth Malone.

“He was a big guy with a booming voice and charismatic persona – and so for a long time, I was just plain scared of him,” Malone said. “But as I worked more with him as a director, I learned from him and trusted him and respected him.”

Malone played Hodel in a production of Fiddler on the Roof that McHale directed, and she remembers not being able to get through a rehearsal of the goodbye scene with her father because she and McHale were both weeping. “I realized that day it wasn’t Bill’s size or his voice or even his persona that made him a giant – it was his huge heart,” Malone said. “Everyone who has come after him has seemed a little smaller by comparison.”

Ashford, who won a Tony Award for You Can’t Take It With You and depending on world events will reprise Sunday in the Park with George in London this June with Jake Gyllenhaal, remembers being summoned to McHale’s office at the Country Playhouse when she was just 13. He had just given Ashford her first job as an Equity actor, in My Fair Lady.

“Papa Bill brought me into his office to explain how important our Actors Equity union was for professional actors,” Ashford said. “He said that actors deserve to have insurance and a pension like everyone else, and that as storytellers, we offer a valuable service. Theatre is one of the necessities of a fruitful society. Bill taught me how to be a professional and to respect my craft. I’m so grateful I got to be one of the many blessed by his greatness.”

One of McHale’s best friends was George Lee Andrews, who performed in many shows at Country Dinner Playhouse and holds the Guinness World Record for the most performances in the same Broadway show, having appeared in 9,382 performances of The Phantom of the Opera over 23 years. Andrews considered McHale his brother. “He was my mentor and best friend from 1960 when we met, even before my first days in the theatre,” he wrote on Facebook. “His beautiful voice and generous heart touched us all.”

“It wasn’t Bill’s size or his voice or even is persona that made him a giant – it was his huge heart.” – Beth Malone

There was simply no one else like Bill McHale, said his Country Dinner Playhouse protégé, Paul Dwyer. “And I wouldn’t have had any of the artistic success I have had without his guidance.”

In 1970, Sam Newton and Bob Boren opened the 470-seat Country Dinner Playhouse on 5.8 acres of what, at the time, was empty prairie for as far as the eye could see. The land cost Newton and Boren just 50 cents a square foot “because it was the middle of nowhere,” said McHale, who came to Colorado for a job prospect, took one look at the Rockies and called his pregnant wife to say, “Honey, we are moving to Colorado.” In fact, Dwyer added, “Bill moved out here in a Volkswagen bus with four kids, $1,500 in his pocket – and no job.” Newton and Boren saw McHale performing Broadway songs at a local nightclub and recruited him to serve as the Playhouse’s first artistic director.

McHale helped build Country Dinner Playhouse into the state’s second-largest theater. Newton and Boren gradually created a circuit of five dinner theatres around the country that collectively became known as the Windmill Dinner Theatres. McHale would stage a show at the Country Dinner Playhouse, then move on to direct it in the next city, and so on. “An actor could get hired by Bill and conceivably spend the next year and half gainfully employed,” Dwyer said.

The iconic Barnstormers – the food servers who performed before every show, were McHale’s idea. He was also known to perform in a show or two himself, notably as Leadville Johnny Brown in The Unsinkable Molly Brown, Emile deBeque in South Pacific, Charlie Anderson in Shenandoah, Fred Graham in Kiss Me Kate, and Harold Hill in The Music Man. Composer Meredith Willson attended a performance of The Music Man at the Country Dinner Playhouse “and he absolutely loved Bill’s performance,” Dwyer said.

Bill McHale.

As a singer, Ashford said, “Papa Bill was the most magical baritone I’ve ever heard.” Over time, he became as well-known for his renditions of signature songs as for playing full stage roles. McHale never performed in Man of La Mancha, for example – or even staged it – because he never wanted to subject Country Dinner Playhouse audiences to the rape scene. But his big baritone would often announce his arrival with his rafter-rattling renditions of “The Impossible Dream.” And Cowboy Bill – a proud supporter of the National Western Stock Show – often could be found in the Cowboy Bar near the livestock pit sipping Jack Daniels and singing “Danny Boy.”

Dwyer’s favorite was one you might never expect: “I Dreamed a Dream,” the tearjerker sung by young Fantine from the musical Les Misérables. “Bill’s take on that song was just gorgeous,” Dwyer said. “It choked me up every time.”

McHale, every bit the the face and voice of the Country Dinner Playhouse, was rarely seen on its iconic square stage wearing anything other than a tuxedo. Why? “Because the audience needs to know that something special is going to happen tonight,” Dwyer said. But off stage, Cowboy Bill, who enjoyed the outdoor life of a horseman at his ranch outside Parker, was almost always wearing a cowboy shirt and blue jeans. And that fashion anachronism pretty much sums up the clientele he built at the Country Dinner Playhouse. While his productions were elegant and first-class, his loyal guests were welcome to come as they were, feasting on a steady buffet diet of fried chicken, roast beef, mac-and-cheese and panfish.

When McHale was given the Colorado Theatre Guild’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010, his first reaction was: “Are you sure you’ve got the right guy?” McHale always said he thought his greatest lifetime achievement was getting his wife of 65 years, Arlene Corrigan, to date him when he was a teenager.

McHale was born February 1, 1934, in Chicago. He studied for the priesthood for three years at a seminary outside of St. Louis. “But then I went off the deep end,” he said. “I left and immediately enrolled in the co-ed school.” He soon met Arlene and asked her out. She turned him down flat.

Why?

“She thought I was stuck up,” McHale said. “But I eventually won her over.”

Together they had five children, 12 grandchildren and three great grandchildren.

Bill McHale in ‘Kismet.’

“We all thought we were his favorites,” said Maureen McHale Dailey. “While my dad loved the theatre and the beauty it represented, he loved his wife and family even more. Daddy gave us a life filled with mountains and fishing and camping, and his grandchildren remember him with so much love and laughter as well.”

While musicals were the staple of the Country Dinner Playhouse, staging one non-musical play each winter was McHale’s pleasure for 30 years. When he retired in 2000, he went out not just with a bang but also a choke, a dagger, an ax, a hypodermic needle, a shove and a booby trap. McHale’s 142nd and final Country Dinner Playhouse production he directed was the classic 1939 Agatha Christie murder mystery “Ten Little Indians.”

Of all his shows, he once said, his favorite was probably directing the Colorado premiere of Phantom by Maury Yeston and Arthur Kopit. It starred Keith Rice and Tamra Hayden and ran for 20 weeks. McHale played the Phantom’s father.

Seven years after McHale’s retirement, the Country Dinner Playhouse was shuttered without notice during a run of Evita in May 2007. Both actors and audiences arrived in the rain only to discover the front door chained shut. But in one of the most memorable moments in Colorado theatre history, the shell-shocked cast went ahead and performed the entire show in the parking lot, powered only by a generator and lit by headlights from nearby cars. It was, as actor Charlie Schmidt put it at the time, “part funeral and part musical-theater Woodstock.” As word spread, McHale was among those who came down to witness the day the music died in a drizzling rain.

“I remember water was streaming off the roof, and it looked to me like the theater was weeping,” McHale said.

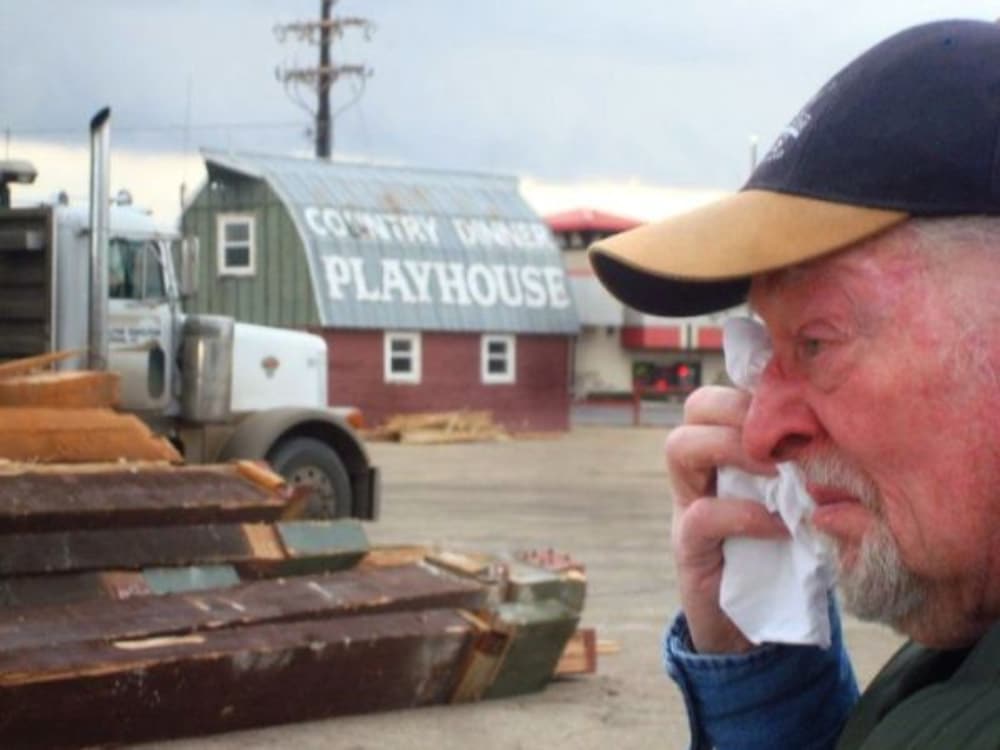

Bill McHale at the demolition of the Country Dinner Playhouse in 2010. Photo by Brian Smith.

After three years idle, the Playhouse was torn down to make room for a Restaurant Depot in 2010. McHale again was among a steady stream of former employees and patrons who stopped by to witness the destruction, but he couldn’t stay for long. “It was too difficult,” he said, “so we had to leave.”

Bill McHale sings ‘The Impossible Dream’ at a Country Dinner Playhouse reunion. Photo by John Moore.

But as McHale considered the gaping hole left in the south end of the playhouse by a single excavator with its huge, biting jaw, he wondered what would remain of his legacy after all the rubble was hauled away.

“Maybe it’s romantic, but I’ve always thought any theater has a soul,” McHale said. Asked what he thought might happen to this one, he said: “I hope its legacy resides in the actors who performed here and loved that theater, and in all those who attended.”

In his later years, McHale joined the board of the historic Elitch Theatre to assist in its restoration capital campaign. At a reunion of Country Dinner Playhouse artists and audiences in 2010, McHale sang “The Impossible Dream” to thunderous applause. Among those who teared up was Susan Long, who had starred for McHale in “Oklahoma” back in 1970.

“When Bill McHale sings ‘The Impossible Dream,’ there’s no metaphor here,” Long said at the time. “He’s lived it.”

For McHale, the impossible dream was quite simple. And, it turns out, possible.

“I always thought entertaining people is what theater is all about,” McHale said. “We are not here just to make money, but to help people forget whatever stress or trauma they may be going through in life.”

McHale is survived by his wife, Arlene, and children Mary Therese, Brian (Cindy), Maureen (Lee), Brett (Shauna) and Julie (Vince). Details of a memorial service will be updated here when they become available.

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theatre critics in the U.S. by American Theatre Magazine. He has since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center’s Senior Arts Journalist.