DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

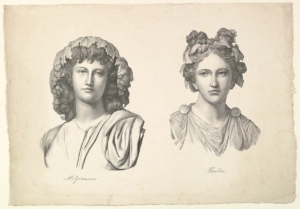

Melpomene and Thalia by Johann Gottfried Schadow. Photo courtesy of The Met

While the names Thalia and Melpomene might mean nothing to you, you would certainly recognize their faces. Also known as Sock and Buskin, the iconic representation of theatre features two masks with familiar laughing and crying faces. Thalia is one of the nine Muses in Greek mythology, the patron of Comedy, represented with the laughing mask. Melpomene is also one of the nine Muses, the patron of Tragedy, represented with the crying mask. Their faces define the two types of drama that have existed since the origin of theatre: comedy and tragedy.

Masks were no longer utilized by performers in Shakespeare’s time, but the playwright still took advantage of the defining literary characteristics originated by early Greek theatre. Because of this, Shakespeare’s repertoire has been divided into the comic and tragic genres.

Much Ado About Nothing has been labeled a comedy with its humorous language, silly situations, and ultimately happy ending. But a central theme to the play is trickery and deceit; something much darker lies hidden beneath the gilded surface, setting up the tragic comedy of the play.

The play begins with a man named Leonato, his daughter Hero, and his niece Beatrice as they welcome a group of friends, returning victorious from war, to their home. Among these friends are the prince Don Pedro, two young soldiers named Claudio and Benedick, and Don Pedro’s illegitimate brother Don John. Upon their arrival, Benedick and Beatrice are shown to already be familiar friends while Claudio falls in love with Hero at first sight. The rest of the play follows the ups and downs of love, friendship, and loyalty.

Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing. Painting by Robert Alexander Hillingford

Benign tricks come into play throughout the first few acts, but these are generally good-natured between friends, including the plot to dupe Benedick and Beatrice into falling in love. Speaking loudly to one another for Benedick to overhear, his friends declare that Beatrice loves Benedick so passionately that her unrequited love might drive her insane. Meanwhile, Beatrice’s friends play the exact same trick. Beatrice comes to the same conclusion as Benedick: they must love the other in return.

However, a seed of darkness is planted early on by Don John, who attempts to thwart these friendly games for his own entertainment. Fueled solely by jealousy as the illegitimate brother of the much-beloved Don Pedro, Don John employs evil plots that would severely damage the victims. Don John says himself, “though I cannot be said to be a flattering honest man, it must not be denied but I am a plain-dealing villain” (I.iii.23–25).

Don John’s evil is unparalleled in any Shakespearean comedy, more often compared to the cunning Iago in the Shakespearean tragedy Othello. Don John plots twice to disrupt the marriage between Claudio and Hero, for no personal gain. Though jealousy is a common plot device in Shakespeare’s work, it is more often used for humor in comedies. In Much Ado About Nothing, the spoilt wedding in Act IV diverts the narrative in an unexpected way. Don John’s plot has succeeded, with Hero left unconscious after Claudio’s denouncement of her in front of their wedding guests.

William Shakespeare

In the aftermath of Claudio’s public rejection, Hero and her family struggle to figure out why Claudio made false claims against Hero. The friar steps forward to suggest Hero should pretend to be dead, to work out the truth of the situation at hand. At a time when Romeo and Juliet was immensely popular, the friar’s suggested solution was intended to leave audiences expecting a tragic ending.

With Hero believed dead, police intervention reveals Don John fabricated lies about Hero to Claudio. In light of the truth, Hero and Claudio reunite with a happy ending: a double wedding between the two couples, Hero and Claudio and Beatrice and Benedick.

Taking a step back, it’s clear that two types of deception are used in Much Ado About Nothing. Don John’s plots are obviously malicious, while the plot conceived by the friar resolved a situation with good intent. However, it is sometimes difficult for the audience to distinguish between the good and the bad, the comic and the tragic. In the end, deceit is neither purely positive nor purely negative: it is simply a means to an end. Hence the title, Much Ado About Nothing. The foibles that result from deceit throughout the play keep the story moving, but don’t result in any major consequences.

DETAILS

Much Ado About Nothing

Sep 30-Nov 6 • Kilstrom Theatre

Tickets