DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

From the archives: this article was originally published on May 17, 2022

By Rowena Alegría, Chief Storyteller for the City and County of Denver

From Denver’s earliest years – when the land that would become the Mile High City was better known as a gathering place for Ute, Cheyenne, Arapaho and other Native nations – Chicanos/Latinés/Mexicanos have taken on giants including poverty, racism, displacement, exclusion and lack of resources. And many wound up heroes for Denver and beyond.

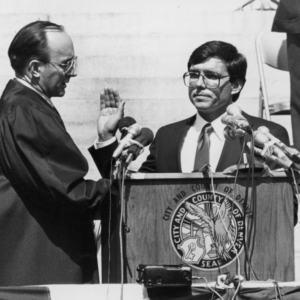

In the late 1980s, when Denver’s first Latiné mayor proposed moving the airport 25 miles outside the city, critics called the plan “Federico’s Folly.” Twenty-seven years later, Denver International Airport is the third-busiest airport in the world and a primary economic driver for the state and the region, generating more than $33.5 billion annually. Federico Peña served the city as mayor from 1983-1991 and went on to serve the nation as President Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Transportation and Secretary of Energy from 1993-1998. The boulevard to the airport is named to honor his contributions, as is a community health center in Southwest Denver.

Frederico Peña. Photo credit: Denver Public Library

The first Chicana voted into the Colorado Legislature worked as a manicurist, had earned a GED and was attending what was then Metropolitan State College. She was also mother of four.

“The idea that you could get elected with a husband and children was radical,” Pat Schroeder, who was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1972 and served until 1997, told The Denver Post upon Benavidez’s death in 2013. “She broke phenomenal ground there.”

In those days, women couldn’t get a credit card in their own name and rarely held elected office, and yet community activist Elizabeth “Betty” Benavidez was voted into the state House in 1970. She opened the door for other Latinés to be elected to public office, including Polly Baca, the first Latiné to serve in both chambers of the Colorado General Assembly; Ramona Martinez, first Latiné president of the Denver City Council; Lucia Guzman, first Latiné lesbian to serve as Minority Leader in the Colorado General Assembly; Rosemary Rodriguez, who has served Denver on City Council, as Clerk and Recorder and on the Denver Public Schools board; and many others. The list, now, is long and growing. At present, and for the first time, five members of the Denver City Council are Latiné. And fourteen of the state’s one-hundred lawmakers are Latiné.

When it comes to taking on giants, Denver has raised its share of activists. In the 1950s, when a local newspaper wrote about the “Spanish American Problem,” a protest led to the creation of the Good Americans Organization to promote civil rights and improve Latiné neighborhoods. Led by Francisco “Paco” Sanchez, who also founded the city’s first Spanish-language radio station, the GAO became the first private organization in Denver to fund low-income housing projects.

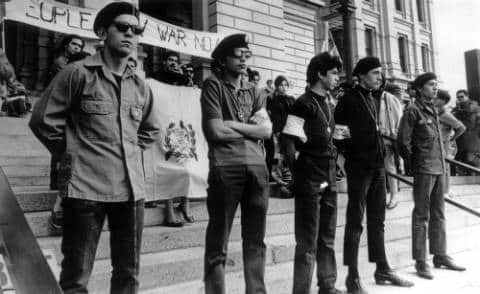

Youths attending Corky Gonzales speech at the State Capitol circa 1968. Photo credit: Denver Public Library

In 1968, Guadalupe “Lupe” Briseño created the National Floral Workers Organization to protest miserable working conditions at a small floral plant in Brighton. Strikers gained local and national support but didn’t get a union. They did, however, inspire others in Denver and elsewhere.

Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales began as a boxer. A good one. He ended his professional career with a 65-9-1 record. For his 1988 induction to the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame, organizers claimed, “Tickets to his fights were as scarce as Denver Broncos’ tickets are in the twenty-first century.”

Also a business owner and poet, Gonzales became a voice against social injustice. He marched with other civil rights leaders, including César Chávez and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Gonzales encouraged Chicanos to be proud of their roots and work to better their communities. The Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales branch of the Denver Public Library opened on West Colfax in early 2015. His children and grandchildren carry on his legacy and include Chicana activist Nita Gonzales; Rudy Gonzales, Executive Director of Servicios de la Raza (services for the people); and Rep. Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez, a democrat representing Denver’s District 4.

Dr. Martha Urioste. Photo courtesy of the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame

The influence of the Chicano Movement, which also sought to address land rights, labor issues, and equity in education and representation, can still be seen in stark bright colors across the city, for starters in education and art.

Denver is a rare city in that it offers access to Montessori education for children from infants through high school, beginning at age three in Denver Public Schools. Dr. Martha Urioste helped launch what has become its own movement across the city. She worked 45 years in the district advocating for a change in the school system. “Testing, testing, testing,” she told the Denver Office of Storytelling. “The kids are bored!”

Urioste was inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame in 2000. She’s joined there by activist Briseño, educators Anna Jo Garcia Haynes, who brought the Head Start program to Denver, founded Mile High Early Learning, co-founded the Colorado Children’s Campaign and was a driving force behind the Denver Preschool Program; Lena Lovato Archuleta, the first Latiné principal in the Denver Public Schools; and other phenomenal Latinés including Juana Bordas, who is an author and business owner, founder of Mi Casa Resource Center and the Circle of Latina Leadership.

When it comes to art, Chicanos are represented in everything from literature, music and dance to sculpture and painting and just about everything in between. Author Kali Fajardo-Anstine is author of Sabrina & Corina, a widely acclaimed story collection, with debut novel Woman of Light coming next month, and Bobby LeFebre is a playwright and performer who was named the state’s youngest and first poet of color to serve as Colorado poet laureate by Gov. Jared Polis in 2019.

Photo courtesy of ArtistiCO

For decades, for example, Grupo Folklórico Sabor Latino led by Lorenzo Ramirez, Fiesta Colorado Dance Company, led by Jeanette Trujillo, and Grupo Tlaloc Danza Azteca, led by Carlos Castañeda and Donna Vigil-Castañeda, have been bringing a cultural beat, as well as traditional ceremony, to Denver. They are joined now by Artisti-CO dance company, founded just last year by José Rosales and Alfonso “Poncho” Meraza Prudente, both former principal soloists for the internationally renowned Ballet Folklórico De México de Amalia Hernández. Artisti-CO is already bringing to the city an exciting approach to performance and expression through movement.

Denver has made its mark in world music, too, including guitarists Manuel Molina and Miguel Espinoza and bands including Conjunto Colores, Roka Hueka, Debajo del Agua and more.

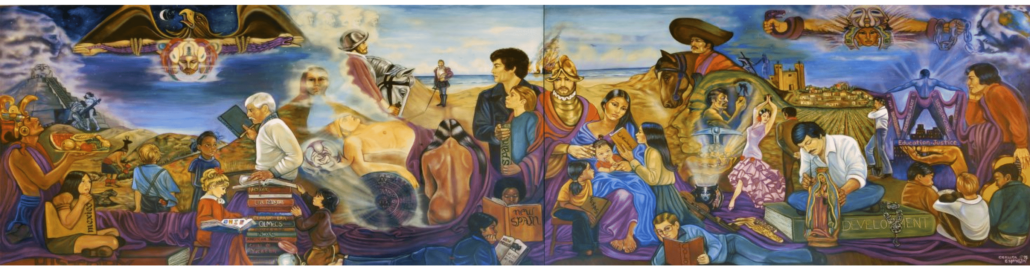

Pasado, Presente, Futuro mural by Carlota EspinoZa. Photo Credit: Denver Public Library

It’s easy to see, literally, how Chicano artists have worked to represent the untold history of Mexicanos in Denver. According to History Colorado, there are more than 40 historic murals around the state, including the iconic wall of the La Alma Recreation Center, painted by Emanuel Martinez, and the “Pasado, Presente, Futuro” mural, which is part of Denver’s John “Thunderbird Man” Emhoolah, Jr. Branch Library and was painted by Carlota EspinoZa. Earlier this month, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named the historic Chicano/a/x Community Murals of Colorado to its 2022 list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. The hope is that the effort will not only create awareness of the works but spur action to protect and preserve the historic artwork.

Dr. Nicki Gonzales. Photo Credit: Regis University

The City and County of Denver led another effort to document and preserve the impact of Mexicanos/Chicanos/Latinés on Denver. In 2022, for the first time ever, the city took culture and ethnicity into account for historic preservation planning purposes when Community Planning and Development’s Landmark Preservation team created the city’s first Latino/Chicano Historic Context. State Historian Dr. Nicki Gonzales, the first Latiné to hold the post, was contracted along with consultant Mead and Hunt to engage community, research history and honor contributions to the city. After more than a year’s work, they released a 200-page report along with a companion film created by the Denver Office of Storytelling titled “¡Qué Viva la Raza! Honoring a Denver Legacy,” which captured on film the history in community voices. Still, the effort only scratched the surface, with much more work to be done with other marginalized communities as well.