DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

This article was published on August 30, 2019

EDITOR’S NOTE: Miss Saigon, inspired by the opera Madame Butterfly, tells one very specific story of the Vietnam War. It does not attempt to convey the breadth of the Asian American experience then or since. The DCPA NewsCenter has compiled a series of real-life stories of Asian Americans from vastly different backgrounds and countries of origin whose stories are both dramatic and dramatically different. We continue with Jackie Nguyen, both a Miss Saigon cast member and a language consultant for the show. Please note that we have chosen to honor the authentic spellings for Viêt Nam and Sài Gòn, respectively.

“They were bullied in Viêt Nam for being mixed race, and they were bullied in America for being mixed race,” said Nguyen. “They never really fit in anywhere.”

“They were bullied in Viêt Nam for being mixed race, and they were bullied in America for being mixed race,” said Nguyen. “They never really fit in anywhere.”

The story of Nguyen’s mother, Minh, closely resembles that of Kim in Miss Saigon. Like Kim, Minh Nguyen was 17 when she met and married an American G.I. with whom she had three sons. “At the time, many Southern Viêtnamese women saw these soldiers as heroes and saviors, essentially because they were fighting for our side,” Nguyen said. “Sài Gòn was just flooded with Americans at the time, and that appealed to many women.”

When the G.I. returned to the U.S. in 1972, Minh chose to stay in Viêt Nam with her boys, in part because she had a good job as a telephone operator for the government. Even after Sài Gòn fell to the communists in 1975, Minh stubbornly remained for another nine difficult years that eventually left her starving and homeless before her husband helped her to escape to Florida in 1984.

“A lot of love stories from the Viêt Nam War are brief,” said Jackie. But Minh’s marriage survived until 1986. After a divorce, Minh joined a larger Viêtnamese community in California, where she met and married a fellow Viêtnamese immigrant. Jackie was born three years later, though her father soon abandoned the family.

“This is not some great-great-grandma from generations past I’m talking about. It’s my mom.”

“We were part of a huge group of first-generation Viêtnamese American kids who were caught between two worlds,” she said. “We were raised in the Viêtnamese culture at home, but I was required to speak English at school. We all felt very torn. I’m obviously very proud to be Viêtnamese now, but as a kid I just wanted to be white so badly. I just wanted to eat Burger King like the rest of the kids.”

It was seeing Miss Saigon that convinced Nguyen to become a performer. “Miss Saigon was the first musical I ever saw, period,” said Nguyen, who in 2012 became the first Viêtnamese American actor to play the leading role of Kim in any American production of Miss Saigon. She now performs an ensemble role in the national tour, and serves as a language consultant for the show.

“I am having full-circle moment,” she said. “I’m performing in this Broadway revival of the show that first encouraged me to do musical theater as a career. And this show has given me incredible opportunity to voice my story and also have a career and health insurance and all the things that come with having a job.”

Here are more excerpts from John Moore’s conversation with Jackie Nguyen:

John Moore: How did your mom meet your brothers’ father?

Jackie Nguyen: It’s a war story. My mother’s English is really great so she was put on duty to translate for the Viêtnamese and Americans. Honestly, I have no idea what he did in the Army. I know that my mom fell in love with him and they met up all the time in Sài Gòn. They married and had three sons. But I don’t know much more than that. My mother always says, “It doesn’t matter. You don’t need to know.”

John Moore: They had to be together for a long time to have three children while the war was going on.

Jackie Nguyen: It’s funny because our musical starts with all these women desperately trying to find an American G.I. to marry so they can leave and get a visa. Here were these new, strong, white men they weren’t used to seeing. That was the type of man they wanted because back then, you had no idea what side the Viêtnamese men were fighting for. You never knew. My mother said the American soldiers were coveted not just because of their unique look, but for what they represented. They represented freedom and being able to escape communism.

John Moore: Does your mom talk to you much about her harrowing escape from Viêt Nam?

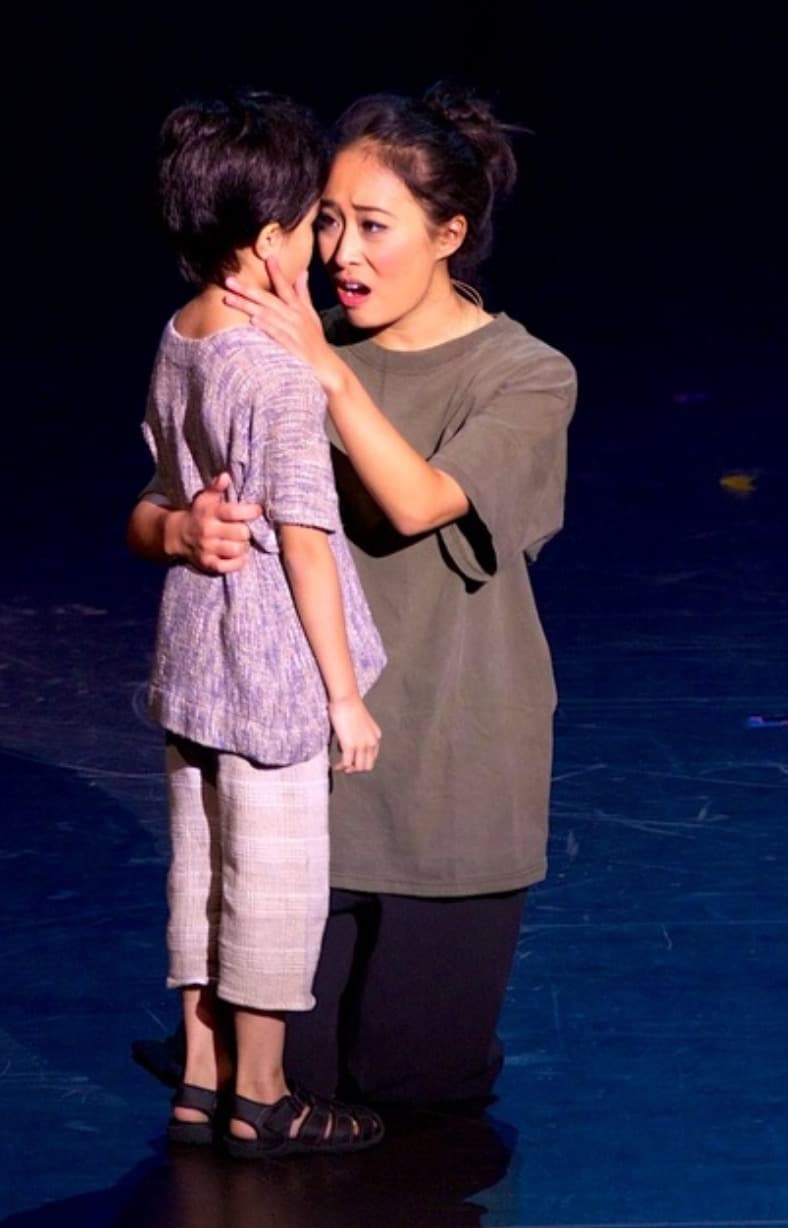

When Jackie Nguyen starred in the McCoy Rigby Conservatory of the Arts’ production of Miss Saigon in 2013, she became the first Vietnamese American actress to ever play Kim. She later played the role again in China.

Jackie Nguyen: I often have to explain that this is not some great-great-grandma from generations past I’m talking about. It’s my mom. And it’s definitely close to my heart. But she doesn’t really talk too much about it because it’s really hard for her. It definitely had an impact on how she raised me, on how she views life and on the lessons she’s taught me.

John Moore: There are so many parallels between her story and Kim’s.

Jackie Nguyen: My mom’s narrative is one of millions of Viêtnamese who escaped communism in different ways, but her story does specifically relate to her falling in love with an American G.I. at age 17 and then him helping her come over. That shows you there are people here in America who are very close to us and have experienced exactly what our musical portrays.

John Moore: Tell me more about why it took nine years for your mother to get to America.

Jackie Nguyen: For the first five years, my mother was convinced that communism was going to be over at any time, so she didn’t want to leave her country. If you were an American G.I., there was a process where once a year, you could bring your kids over to America. But every time my brothers’ dad would try to get my mother over, she would say, “No, communism is going to end and everything will be fine.” But then life got so difficult for her. They didn’t have food. They didn’t have a home. So my mom was like, “All right. I guess we have no other option but to leave.” And so in 1984, my brothers’ father helped them all come over to Florida, where he is from. They stayed there for a few years. When my mom and their dad divorced, my mom decided to move to California because that’s where so many of her friends had settled when they came here. There weren’t many Viêtnamese people in Florida.

John Moore: Has she ever gone back to Viêt Nam?

Jackie Nguyen: She’s been in America for 35 years now and she’s never gone back because she doesn’t want to visit a country that’s still communist. She’s deeply against it.

John Moore: So you were born in America to two Viêtnamese parents and raised by a single mother. Tell me more about growing up in California.

Jackie Nguyen: There is a huge group of us who are first-generation Viêtnamese American. And we all had this unique experience growing up because our parents so badly wanted us to have freedom and be Americanized. But at the same time, they didn’t know the first thing about American culture, so they raised us in the Viêtnamese culture. I had a very distorted upbringing because my mom would want me to speak Viêtnamese at home, but I was required to speak English at school.

John Moore: And what about your brothers?

Jackie Nguyen: It was very strange because my brothers grew up in Viêt Nam, but they looked American. I grew up in America, but I look Viêtnamese. And so I always had a different relationship with my brothers. They’re way more traditional. They’re way more Viêtnamese than I am. They speak the language. They read it. They write it. I can only speak the language. It’s weird. We were in America, and we were Americans, but our parents were not. I grew up thinking that being Asian was not cool. I grew up thinking that being blonde, blue-eyed and fair-skinned was cool. I wanted to be white so badly. And all my friends thought so, too. So we refused to speak Viêtnamese at home. I was always angry that my mom wanted to eat Viêtnamese food. But I was 10. It took me a while to understand the complexity of what my mom was going through.

“I hope the local Viêtnamese community will feel like this musical is a tribute to that time in their lives when they really struggled.”

The story of Jackie Nguyen’s mother closely resembles that of Kim in ‘Miss Saigon.’ Photo by Matthew Murphy.

John Moore: What do you want people to know about this new version of Miss Saigon?

Jackie Nguyen: My perspective is pretty unique, being Viêtnamese. I want them to know this show was written a really long time ago, and I want people to know that we’ve all done a lot of work to make it as real as possible. It’s authentically cast with at least 30 actors who come from an Asian heritage. Two of us – myself and another actor who is Viêtnamese – work with cast members to make sure that when they are speaking Viêtnamese, the inflection and the dialect are correct. I also want them to know this is a Broadway musical. We’re trying to entertain and enlighten and bring emotion to people who need an escape.

John Moore: And what is your specific message to the Asian American community living in Denver?

Jackie Nguyen: First of all, the American style of musical theatre doesn’t exist in Viêt Nam, so first and foremost, I would encourage them to come see our musical because it will be a new art form to most of them. And second, Miss Saigon will be the perfect introduction to musical theatre because the story has to do with what the majority of that community had to go through. These stories are real, and these women who did desperate things to fight and survive are real. I hope the local Viêtnamese community will feel like this musical is a tribute to that time in their lives when they really struggled. We are attempting to honor that.

This is the story of a young Vietnamese woman named Kim who is orphaned by war and forced to work in a bar run by a notorious character known as the Engineer. There she meets and falls in love with an American G.I. named Chris, but they are torn apart by the fall of Sài Gòn. For three years, Kim goes on an epic journey of survival to find her way back to Chris, who has no idea he’s fathered a son. Featuring stunning spectacle and a sensational cast of 42 performing a score that includes “The Heat is On in Saigon,” “The Movie in My Mind,” “Last Night of the World” and “American Dream.”

This is the story of a young Vietnamese woman named Kim who is orphaned by war and forced to work in a bar run by a notorious character known as the Engineer. There she meets and falls in love with an American G.I. named Chris, but they are torn apart by the fall of Sài Gòn. For three years, Kim goes on an epic journey of survival to find her way back to Chris, who has no idea he’s fathered a son. Featuring stunning spectacle and a sensational cast of 42 performing a score that includes “The Heat is On in Saigon,” “The Movie in My Mind,” “Last Night of the World” and “American Dream.”