DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

This article was published on September 19, 2016

Note: John Moore conducted the following interview just before the first local production of Edward Albee’s ‘The Goat, or Who is Sylvia‘ was presented by Denver’s Curious Theatre in January 2005. ‘The Goat’ is the shocking tale of a family whose lives crumble when the patriarch, Martin, falls in love with a goat, severely testing the limits of this ostensibly liberal society. Albee died Friday at age 88.

Edward Albee

John Moore: Does it ever stop being amusing to you to observe how people respond to your plays? My specific reference in asking this question comes from looking back at the harsh batch of initial reviews for The Goat, which, shall we say, did not seem to indicate that the play would go on to win the 2002 Tony Award for Best Play.

Edward Albee: What was interesting about that is when we changed casts in the middle of the run and put Sally Field and Bill Irwin in, some of the critics came back – and they changed their minds. The lady from Newsday issued a total mea culpa, as a matter of fact. She said she had completely misunderstood the play and now believed it was a wonderful play.

John Moore: That’s not the first time that has happened to you,

Edward Albee: No, but it usually doesn’t happen during the initial production. It usually happens when the play comes back 10 or 15 years later. Then everybody says, ‘Well, we don’t know what everybody was so unhappy about. This is first-rate.’ It’s always amusing and interesting, yes. You know that it’s all going to change, so why pay attention to it?

John Moore: It must be odd for you though, because these are the same people who constantly refer to you, almost adjectivally, as “America’s greatest living playwright.” And yet at the same time they compare and contrast everything you write today to whatever it is you were writing 40 years ago.

Edward Albee: I know. You change, and your work changes. I know that my plays are changing. They are becoming different from the ones I wrote 40 years ago. I think maybe my craft is a little more in hand. I know what I am doing a little more precisely, and I think maybe I am asking more interesting questions. I certainly don’t have any more answers.

John Moore: So what kinds of questions you are asking now?

Edward Albee: The Goat asks so many questions about the limits of our tolerance. Can we imagine this happening to us? How would we respond if this happened in our own families? That’s what I want people to do with this play, of course. Not just sit there on a throne and pass judgment on other people.

John Moore: I read in your introduction to your Collected Plays that it’s no fun for you to talk about what your plays are about. That it’s fun for you to hear what other people think your plays are about.

Curious Theatre’s 2005 production of ‘The Goat’ with Mare Trevathan and Robert Reid.

Edward Albee: I don’t want to talk about what my plays are about. I want to talk about other things. The Goat is about 90 minutes. That’s what it’s about. Any play that’s worthwhile can’t be defined in a couple of sentences because it’s about every single thing from the beginning to the end. Also it happens to be about everything that happens before the play begins. And if all the characters haven’t been killed off, the play is also about what happens to the characters after the plays are over. So it’s fruitless to even try to talk about that.

John Moore: May I ask you about my own response to the play?

Edward Albee: Sure, of course.

John Moore: Upon my first reading, I assumed this was a play about Martin’s wife, Stevie. She was being put in the petri dish as an experiment to explore the gradations of infidelity, and specifically a woman’s reaction to being cheated upon.

Edward Albee: You must understand that her reaction would be quite different if it were another woman, rather than a female goat.

John Moore: Absolutely. Which is why I want to ask how you came to decide not to make this a story about another woman, but instead push the limits and see how people respond to a husband falling in love with a goat?

Edward Albee: I want people to imagine the unimaginable. I want them to consider what they don’t think they should be able to consider. I want people to break down the barriers of convenience that they have built up for themselves.

John Moore: I saw in the goat a metaphor for everything we as a society find unacceptable in the behavior of others.

Edward Albee: Yeah, but never forget – it’s also a real goat. It’s not a metaphorical goat.

John Moore: But I am assuming you want us to consider our attitudes about forbidden loves of all kinds.

Edward Albee: Of course.

John Moore: That was driven home for me this weekend when I went to see two movies: Closer and Kinsey. I thought they both spoke to some of the same issues you raise in The Goat.

John Moore: That was driven home for me this weekend when I went to see two movies: Closer and Kinsey. I thought they both spoke to some of the same issues you raise in The Goat.

Edward Albee: I didn’t see Closer because I didn’t like the play when I saw it in London. But I saw Kinsey, and I thought it was a pretty good movie.

John Moore: Did you see in that movie some parallels to The Goat?

Edward Albee: Now that you mention it, I guess so, sure. The other interesting thing is that every once in a while people would get up and walk out during The Goat. I didn’t have an intermission, so that made it harder for people to sneak out. That’s not why I didn’t have an intermission. I just felt the intensity of the play would be broken if we had one. But here’s the thing: More people would walk out when Billy kissed his father.

John Moore: More so than the revelation that Martin was sleeping with a goat?

Edward Albee: Yes. Even more so than when we talked about the sexual implications of the crucifixion. More people walked out after the kiss.

John Moore: What do you think that says about us?

Edward Albee: That it’s a knee-jerk reaction. That’s something we can react to with social approval.

John Moore: When you think about the list of all lingering societal taboos, do you find that homosexuality is still the biggest?

The DCPA Theatre Company’s 1997 production of ‘Three Tall Women.’

Edward Albee: That’s the one society is taking a stand on, and I think that is the result of this recent (2004 presidential) election. That kind of reaction is socially acceptable, in the same way that lynching black people used to be.

John Moore: When you say that … when you acknowledge that … what does it do to your spirit? You have been addressing these taboos in very provocative ways for 40 years, and yet it’s 2004…

Edward Albee: Well the good thing about it is it keeps giving me stuff to write about. (laughs). You know, we all hope that people will start behaving the way we want them to, and some problems will go away. But people don’t pay any attention to it … so I keep writing plays.

John Moore: Your play has a title – The Goat – and a subtitle – Who Is Sylvia? – and a sub-subtitle – Notes Toward a Definition of Tragedy. The Greek origin of the word ‘tragedy’ is ‘goat-song’ – and you have a character named Billy, which is similar to ‘Billy goat.’ Did all of that have anything to do with your choice of a goat, as opposed to any other animal? Or was it just a coincidence?

Edward Albee: That was just a wonderful accident. I named the son Billy before I consciously realized that I could use ‘Billy goat’ as a joke. I probably made an unconscious decision.

John Moore: Well it’s a wonderful accident.

Edward Albee: Except that it’s not an accident. It’s a conscious accident. I don’t think there are any accidents.

John Moore: You must be tired of talking about The Goat. And yet it must be fascinating for you to watch as your work rolls out into the heartland, where it is new to everyone.

Edward Albee: Yeah, but Denver is not a terrible city for theatre.

Edward Albee: Yeah, but Denver is not a terrible city for theatre.

John Moore: I wanted to ask you about your continuing and very active interest in the companies that produce your work all over the country. You are one of the only playwrights of your stature who still insists on casting approval for all your plays. Why it still so important for you to be concerned with what companies around the country do with your material?

Edward Albee: Because it’s my play, and I am leasing it to them to produce it. I am anxious to get the best actors and the most accurate production I can get. That’s why I am interested in who the actors are, and who the director is.

John Moore: Has that always been the case with you?

Edward Albee: Oh, yeah. My first producer, Richard Barr, encouraged me to take a very active hand in everything, including set design. He kept reminding me: “It’s your play. That’s the reason everybody is in the room.”

John Moore: Was there some early disaster that prompted all of this?

Edward Albee: Well there was one experiment where I let the producers and the director, everybody, have a free hand – and it was an absolute disaster. So I learned pretty quickly that I can’t do that.

John Moore: You never contemplate retirement, do you?

Edward Albee: What is retirement? I do what I like, pretty much. I am happy writing plays. I am happy getting involved in their productions, and directing, and helping younger playwrights. I suppose I would retire if my mind collapsed. I’ll be 77 in a month and a half, and I keep wondering when middle age is going to end.

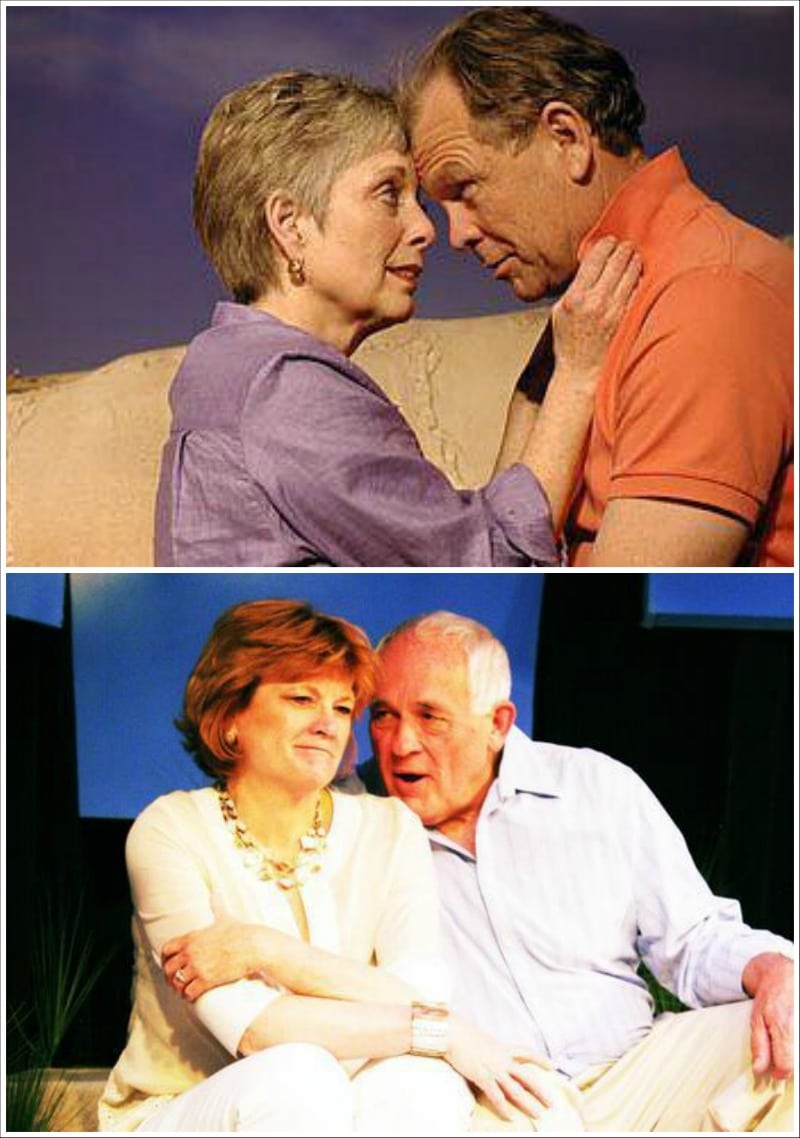

Two local productions of ‘Seascape’: Billie McBride and John Ashton for Modern Muse in 2007, above; Jennifer Condreay and Jim Hunt for Lake Dillon Theatre Company in 2011, below.

John Moore: Final question: What do you think is the state of the new American theatre right now

Edward Albee: Here’s a very simple rule: One out of every 100 plays that is written should be written. The other 99 should not. Maybe one out of every 10 plays that gets produced is worth producing. There is some good stuff, but there is a lot of dross. There are an awful lot of eager and ambitious and sometimes enormously talented people out there. The problem is not with the quality of the work that can be done. The problem is with the quality of the work that is being done to appease an audience that doesn’t want to have its mind strengthened. It’s not the availability of good stuff, but the choice that theatres make and what they do to sell tickets, rather than to educate an audience. That’s a big problem.

John Moore: Would you say that ratio is about the same as it was when you started 40 years ago? Or has the advent of computers made it worse?

Edward Albee: I think probably economics has made it worse. When we did Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf on Broadway in 1962, it cost $48,000 to produce it. Now this new production that we are about to open in Boston is going to cost $1.5 million. We did The Zoo Story together with Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape off-Broadway in 1960 for $2,000. Now it would cost half a million. And so economics have made cowards of knaves.

John Moore: I don’t see that changing anytime soon.

Edward Albee: No, apparently everybody likes to pay too much for tickets and especially they like to pay too much if they are not seeing anything.

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theater critics in the U.S by American Theatre Magazine in 2011. He has since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center’s Senior Arts Journalist.

The Plays of Edward Albee:

The Zoo Story (1958)

The Death of Bessie Smith (1959)

The Sandbox (1959)

Fam and Yam (1959)

The American Dream (1960)

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1961–1962)

The Ballad of the Sad Café (1963)

Tiny Alice (1964)

Malcolm (1965)

A Delicate Balance (1966)

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1966)

Everything in the Garden (1967)

Box and Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung (1968)

All Over (1971)

Seascape (1974)

Listening (1975)

Counting the Ways (1976)

The Lady from Dubuque (1977–1979)

Lolita (1981)

The Man Who Had Three Arms (1981)

Finding the Sun (1983)

Marriage Play (1986–1987)

Three Tall Women (1990–1991)

The Lorca Play (1992)

Fragments (1993)

The Play About the Baby (1996)

Occupant (2001)

The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? (2002)

Knock! Knock! Who’s There!? (2003)

Peter & Jerry, retitled in 2009 to At Home at the Zoo (2004)

Me Myself and I (2007)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!