DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

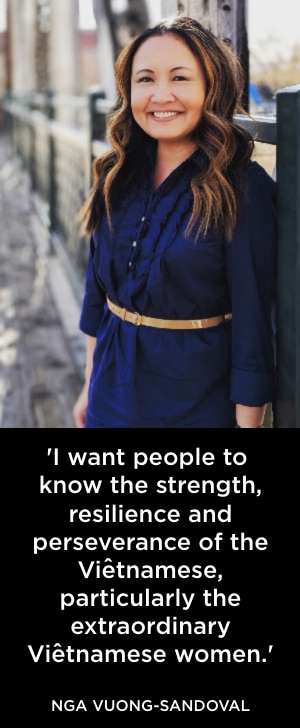

Denver’s Nga Vuong-Sandoval stands before the 2019 Colorado Womxn’s March on Denver (intentionally spelled) in January at Civic Center Park. Photo by Dave Russell at Buffalo Heart Images.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Miss Saigon, inspired by the opera Madame Butterfly, tells one very specific story of the Vietnam War. It does not attempt to convey the breadth of the Asian American experience then or since. The DCPA NewsCenter has compiled a series of real-life stories of Asian Americans from vastly different backgrounds and countries of origin whose stories are both dramatic and dramatically different. We begin with Denver’s Nga Vuong-Sandoval, a refugee, activist, historic preservationist and advocate for Colorado’s refugees. Please note that we have chosen to honor the authentic spellings for Viêt Nam and Sài Gòn, respectively.

Her family had no choice but to leave, she said, because Sài Gòn had become a hell on earth.

“The threat was imminent,” Vuong-Sandoval said. “It was either we left that very moment or we stayed and risked being incarcerated, tortured, killed — or all of the above.”

After several days without food or water, Vuong-Sandoval’s family finally arrived at a refugee camp in Guam, then forcibly relocated to the same camp in Arkansas that serves as the setting for Qui Nguyen’s play Vietgone. Vuong-Sandoval, now an investigator for the Colorado Attorney General’s office, served as a creative consultant for the DCPA Theatre Company’s 2018 production of that play.

After several days without food or water, Vuong-Sandoval’s family finally arrived at a refugee camp in Guam, then forcibly relocated to the same camp in Arkansas that serves as the setting for Qui Nguyen’s play Vietgone. Vuong-Sandoval, now an investigator for the Colorado Attorney General’s office, served as a creative consultant for the DCPA Theatre Company’s 2018 production of that play.

There was no formal refugee resettlement program in Colorado when Vuong-Sandoval’s family arrived.

“We couldn’t foresee what tomorrow held,” she said. “We didn’t know if we would be reunited with our relatives. We didn’t know where our final destination was. We didn’t speak English, and we didn’t know the first thing about American culture. To compound our situation, we had relatives who died in the war. We had just lost our homeland. We lost everything.”

Her father, a high-ranking South Viêtnamese military officer, eventually settled the family in Colorado, which by 1990 had become home to about 5,800 Viêtnamese refugees.

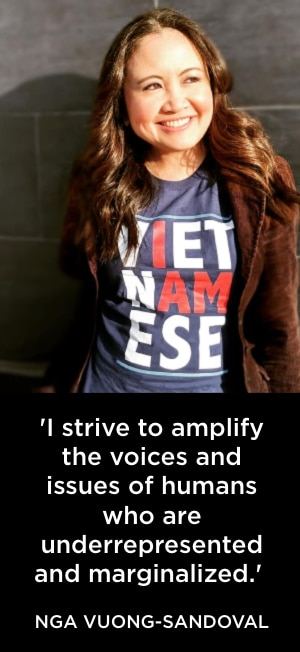

Today, Vuong-Sandoval lends her support and voice to numerous organizations dedicated to refugee resettlement and advocacy, including as a public speaker with Colorado Refugee Speakers Bureau and Lutheran Family Services Rocky Mountains, where she became the first refugee elected to its board of directors.

“My work in the community means everything to me,” she said. “I strive to amplify the voices and issues of humans who are underrepresented and marginalized. Those who are recipients of xenophobia, hatred, racism and intolerance.”

Vuong-Sandoval serves as a Noble Ambassador for the Christina Noble Children’s Foundation, which is committed to alleviating children and their families in poverty in Viêt Nam and Mongolia through health care, education and community development. Children today are still being born with deformities, abnormalities, and birth defects caused by the 20 million tons of Agent Orange that was released by U.S. military during the war and remains in the ecosystem to this day, she said.

“Think about that: Kids are still impacted by Agent Orange that was dropped 50 years ago and will likely impact them for another 50 years according to medical professionals in Viêt Nam,” she said. “Horrendous issues surrounding the aftermath of the Viêt Nam War are rarely presented. These issues aren’t being brought to light.

“Do you see why this is so important to me?”

Here are more excerpts from John Moore’s interview with Nga Vuong-Sandoval:

John Moore: Can you tell me more about the circumstances of your family’s departure from Sài Gòn?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: We never chose to leave. As refugees, we were forced to leave because of the dire circumstances we were presented. The Communist regime had aggressively moved its military forces to the south toward Sài Gòn. The threat was imminent. Starvation was rampant. Brutal torture and sexual assault were common from both sides. That’s the grim reality of war. There were things being done to humans during that time that were atrocious, as with any war. We weren’t seeking a “white savior.” We wanted to keep our homeland and we wanted to stay alive – these were our paramount concerns.

John Moore: What was it like when you landed in Guam?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: There was tremendous despair. My parents realized that our homeland had been violently overthrown. They knew that we could never return to Viêt Nam. As civilians, we never chose to be involved in this war and yet we were now refugees. There was an overwhelming sense of sorrow, hopelessness and grief. In addition to the devastating sadness that we all felt, there was complete mayhem. Fleeing our homeland during chaotic circumstances forced us to bring only the bare minimum: Our family and our family photos.

“I believe that the definition of what is an American is becoming increasingly narrow.”

John Moore: And then you were sent to the camp in Arkansas.

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: Yes, and even after losing everything, we were greeted by protesters at the refugee camp who despised the fact that we had arrived in the U.S. An important aspect that never crossed their minds is the fact that we couldn’t go back home, and yet we weren’t accepted in our new home.

John Moore: And so how long were you there?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: At least six months. The Vietnamese diaspora was an entirely new concept for the U.S. Our influx caused trepidation and heightened xenophobia toward our community. Additionally, refugee resettlement programs were entirely non-existent, and so the federal government heavily relied upon non-profit and faith-based organizations to assist. The government provided stipends to families who agreed to sponsor Vietnamese families for a brief duration, generally a few months – until we were able to gain financial stability and the ability to self-sustain.

John Moore: Where and when did you eventually begin a stable life with your family?

John Moore: Where and when did you eventually begin a stable life with your family?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: We had to wait for a sponsor family that would accept my entire immediate family, to ensure we would remain intact. We eventually ended up getting a sponsor family in Alabama. Talk about a culture shock.

John Moore: And when did you come to Colorado?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: We were eventually relocated to Colorado Springs. That was our first major integration into the United States. That’s where we actually settled in and had our own home. We eventually were able to attain access to certain things there that would make our quality of life a little bit better, like work and housing.

John Moore: You said your father had been a high-ranking military officer. What was it like for him to have to start over?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: To witness him not being able to utilize his high skills and education, the things that define a person who has been dedicated to his profession for so long, simply based upon a language barrier, was heartbreaking and devastating. Highly educated and highly skilled refugees such as my father were unable to secure skilled employment. The employment system focused on language barriers and failed to recognize his overseas education and professional training.

John Moore: The Viêt Nam War happened nearly 50 years ago. What went through your mind when you saw the recent news of 150 refugees dying when two migrant boats capsized trying to make it from Libya to Europe?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: I thought, “That could have been us.” We had up to 400,000 Viêtnamese refugees die at sea. And that’s not including land. Just at sea. It’s unimaginable for non-refugees to experience this level of trauma, suffering and chaos. There are currently about 26 million refugees worldwide who are undergoing my refugee experience. It’s heartbreaking. It’s even more disturbing that these humans aren’t being welcomed by all.

“I believe that marginalized groups are easy scapegoats for those who have never been underrepresented, marginalized, oppressed or treated as an ‘other.’ “

John Moore: And what do you make of the current political climate in this country?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: I believe that compassion and sympathy should be nonpartisan. Unfortunately, that’s not the mindset from all who can deliver humanitarian legislation. I also believe that marginalized groups are easy scapegoats for those who have never been underrepresented, marginalized, oppressed or treated as an “other.” Instead of looking inward, people are pointing outward at others. It’s easy to do that, as opposed to self–introspection.

John Moore: I just have to ask: Do you feel like an American? Do you feel like this country is your country, given the way that you and your family have been treated?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: That’s a great question, particularly in our current time. I believe that the definition of what is an American is becoming increasingly narrow. I feel like that definition is becoming more representative of those who don’t want us here – and that’s a travesty.

Nga Vuong-Sandoval appears before the City and County of Denver’s proclamation honoring the Việtnamese-American community of Colorado on March 26. Photo by Kevin Beaty, Denverite.

John Moore: Do you feel like your voice is now being heard?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: As part of my social justice advocacy, I want to ensure that my voice serves on behalf of those who are unable to represent themselves, especially the underrepresented or marginalized. Yes, I’ve been fortunate to have had several meaningful opportunities to raise my voice and amplify these issues for communities including refugees and immigrants. I’ve had incredible opportunities to advocate for communities that I deeply care about, but with this privilege comes great responsibility.

John Moore: What are some examples?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: In April, I testified on Colorado Senate Bill 230 Colorado Refugee Services Program in both the House and Senate committee hearings, which passed and was codified into law by Governor Jared Polis on May 28. I was invited to testify specifically on my personal and professional contributions to underscore that refugees like my family arrive with nothing and have lost everything, yet contribute in countless meaningful ways. It was important that I humanize refugees and emphasize the value of all refugees who are fleeing, have fled or are currently waiting on refugee camps, and those who are now on their journey to seek safety and refuge. This message to humanize refugees is paramount. I explained that I began my formal education with not speaking any English to eventually earning a full-ride academic scholarship to college. I’ve dedicated my professional career in public service and dedicated my personal work to advocating for our most vulnerable communities.

John Moore: June 20 is now Colorado World Refugee Day. What does that mean to you?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: Then-Governor John Hickenlooper signed the proclamation on June 20, 2017, to honor and recognize the myriad contributions by our refugee community. I was grateful to participate as a speaker on the steps of the state capitol. I wanted to showcase our incredible refugee community and celebrate our collective accomplishments. There was a moment while I was delivering my speech when I truly realized the gravity of that moment. I began as the little girl at a refugee camp who spoke no English and now was speaking on a day that officially recognized my refugee community. It was surreal.

Nga Vuong-Sandoval served as a creative consultant for the DCPA Theatre Company’s 2018 production of ‘Vietgone.’ She is pictured with the cast on opening night.

John Moore: What was your experience like last year serving as a creative consultant for the DCPA Theatre Company’s 2018 production of Qui Nguyen’s play Vietgone?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: I thought the Denver Center’s approach of reaching out to me as someone who was directly impacted by the Viêt Nam War and who also advocates for this particular community was impressive and absolutely incredible. The Denver Center had contacted me about a year before the actors even arrived in Denver and asked me to review the script for authenticity. I truly appreciated that. The play was written by a Viêtnamese playwright, and his perspective, his portrayal of the Viêtnamese, of the refugee camp, our sentiments toward the war and our angst, were delivered honestly and respectfully. I appreciated the Denver Center not only for being receptive to my suggestions, but also for being respectful to our refugee experience. The entire process was done in the most respectful way. To ensure authenticity and inclusivity, I believe this should become standard practice for the Denver Center to ensure that voices from impacted communities are included for productions that portray underrepresented communities.

John Moore: What do you want audiences coming to see Miss Saigon to know from someone who was there?

Nga Vuong-Sandoval: I want people to know that nothing about war is romantic or pleasant. I want people to know that millions of Viêtnamese were profoundly impacted by the Viêt Nam War. I want people to know that more than a million Viêtnamese lost their lives. I want people to know the strength, resilience and perseverance of the Viêtnamese, particularly the extraordinary Viêtnamese women. I want people to know we only wanted to remain alive and to keep our families together during the war. I want people to know that many half-American children born from American soldiers and Vietnamese women were abandoned by their American fathers and ostracized in Viêt Nam. I want people to know the continued impact of Agent Orange that remains in Viêt Nam’s ecosystem in present day causing profound abnormalities, deformities and birth defects to children who are born and who have yet to be born. Most important, I want people to know how proud we are of our homeland and to be Viêtnamese.

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theater critics in the U.S. by American Theatre Magazine in 2011. He has since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center’s Senior Arts Journalist.

Denver’s Nga Vuong-Sandoval stands before the 2018 Colorado Women’s March on Denver. Photo by Daniel Sauve.