DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

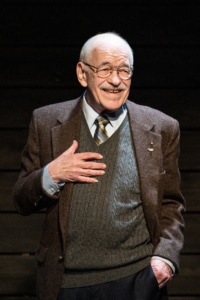

Kenneth Tigar in The Happiest Man on Earth at Barrington Stage. Photo by Daniel Rader

With his wavy white hair, his dapper blue-gray suit and gold-rimmed eyeglasses, the nonagenarian did not look a day over 80.

Standing at a podium at a 2019 Ted Talk, 99-year-old Eddie Jaku looked out at the audience before he began recounting his experiences of Kristallnacht and the five concentration camps he survived. “My dear new friends,” he said to a packed theater in Sydney, Australia. His talk, “A Holocaust Survivor’s Blueprint for Happiness,” has had more than 2.2 million views.

Although he immigrated to Australia decades earlier with his wife, Flore, Jaku (born Abraham Salomon Jakubowicz in 1920) still had the accent of a man who’d begun life in Leipzig, Germany. Kindly would be a good description of Jaku’s demeanor. Only the word has Germanic roots and Jaku shared near the end of his 11-minute talk that he had vowed many things when his first son was born: “From that day until the end of my life, I promised to be happy, to smile, be polite, helpful and kind. I also promised never to put my foot on German soil again.” All were promises kept.

Jaku’s harrowing memories and tenacious hope that those memories might make us (the vast collective us) wiser and, yes, kinder fuels his memoir: The Happiest Man on Earth: The Beautiful Life of an Auschwitz Survivor, published in 2021. He died later that year. He was 101.

In 2023, playwright Mark St. Germain adapted the book for a solo play and sent a draft to the director Ron Lagomarsino. The Happiest Man on Earth starts as cordially as Jaku’s Ted Talk did. “We decided to begin the play with Eddie interacting with the audience,” says Lagomarsino. “He starts out [telling them], ‘I have to speak to my children at synagogue tomorrow and they’ve never heard this story. I don’t know if I can do it.’ So, he sort of includes the audience not as co-conspirators but to join him in the journey.”

Kenneth Tigar in The Happiest Man on Earth at Barrington Stage. Photo by Daniel Rader

Lagomarsino has been with the play since that first draft. He directed the world premiere at Massachusetts’ Barrington Stage Company and its reprise there as well. He also helmed a London production last fall. All starred veteran film and television actor Kenneth Tigar as Jaku.

The memoir isn’t long (not even 200 pages), but it is necessarily relentless. The abject cruelties, the unfathomable losses, the unceasing precarity Jaku bore and witnessed began on Kristallnacht (“Night of Broken Glass”) when Nazis broke into the family home, beat a young Jaku, killed his beloved dachshund, and burned down the house, which had been in his family for 200 years. That was November 9, 1938. Torments did not cease for him until he made his way to Belgium (for a second time) in 1945. And, even after that, his psychic wounds seeped.

“The memoir is chock-full — so many members of his family — so many things that happened to him that you couldn’t possibly put into this piece,” Lagomarsino says. “So, we tried to maintain the essence of the memoir.” For that, he credits the script but also Tigar.

“We were so blessed to have found Ken because he’s truly to the manner born,” Lagomarsino says of his star. “He studied German literature at Harvard. He’s got a Jewish background. He’s so great in the role.”

A couple of decades younger than Jaku, Tigar embodies Jaku as he was at 100 years old but also as a young man living through “my hell on Earth,” as he refers to Auschwitz, the concentration camp in Poland. In the play, he starts out describing his family, his time at a boarding school where he had to assume a non-Jewish name to attend. He relates Germany’s descent into racial madness — the wholesale carnage, the deaths of his beloveds, his own narrow and brief escapes — and then he seems to begin reliving it.

Lagomarsino knew he wanted the play to be physical. A one-person piece, featuring a 100-year-old man just talking would slight theater’s powerful tools — the lighting, sound and scenic design. And he calls on their transformative magic. But, for his lead, says the director, “I had to go day by day and see if Ken was going to go along with me and how much I could push him.” The short answers: “He was” and “a lot.” “The audience will be amazed to see how athletic Ken is,” says Lagomarsino. “He becomes Eddie.”

When Jaku’s grandsons, who control of the rights to their grandfather’s life story, saw video and photos of the actor, they were struck by the family resemblance, says the director. “They said, ‘Oh, my God, we’re looking at our father!’”

So what of the emotional demands of the material? How does a director and his actor live Jaku’s horrific memories repeatedly? Because if they can’t there’s a chance the audience won’t be able to either. Or as Jaku so poignantly poses: “How much can they bear to hear? How much can I bear to remember?”

“First, I think you need the ability to have some relief from that darkness. There is quite a bit of humor in the play. I mean, it’s black humor mostly. Second, I want my actors to feel safe and therefore free to fail, to soar, to whatever it is.” — Ron Lagomarsino, Director

Lagomarsino appreciates the intimacy depicted between Jaku and the imaginary audience. “Jaku actually thanks the audience for allowing him to realize that he has to get over his fear of this, because this is a story that must always be told, and he must tell the story.” It’s the burdensome and vital blessing of the living. One Jaku embraced with such verve toward the end of his life.

The arrival of The Happiest Man on Earth, is, alas, achingly timely. It documents the depravity of Antisemitism, incidents of which are on the rise. But the play is also a testament to Jaku’s deeply humanist grasp of the kinds of civic weakness that undermine moral courage. The kinds of false strength that lead to the cruelties justified in the name of ethnicity, state, fear.

“It’s a challenging experience,” says Lagomarsino not as a caution but as an invitation. “This play is challenging, but anything worthwhile is.”

DETAILS

The Happiest Man on Earth

Sep 19-Nov 2 • Singleton Theatre

Tickets