DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

This article was published on December 9, 2018

Video: Actor Charles Weldon talks about how his life as a truck driver inspired the DCPA Theatre Company’s 2010 world-premiere ‘Mama Hated Diesels.’

Where do you even start to recount the life of actor, director and producer Charles Weldon?

He worked in a California cotton field until he was 17 – and a year later sang on the No. 1 hit song in America. He appeared on “The Dick Clark Show” and toured with James Brown and Fats Domino. He made his Broadway debut at 19 – less than a year after he took up acting – in a 1969 musical that starred none other than Muhammad Ali. In the 1970s, he was a self-described flower child who partied with Richard Pryor. Over the years he worked with Denzel Washington, James Earl Jones, Cicely Tyson and Alfre Woodard. Out of economic necessity, he had two long stints as a cross-country truck driver, tales from which became the basis for the DCPA Theatre Company’s world-premiere Mama Hated Diesels in 2010.

Weldon never went to college. He liked to say “I studied life … at the College of Life.” The man known as much for his laugh as his long list of professional credits died of lung cancer on Friday night in New York. He was 78.

Weldon never went to college. He liked to say “I studied life … at the College of Life.” The man known as much for his laugh as his long list of professional credits died of lung cancer on Friday night in New York. He was 78.

“He had a commitment to the arts, and he was adored by many for his hard work as an actor,” Lisa Mapps-Weldon, his daughter-in-law, said Saturday in announcing Weldon’s death. “The only way to describe his life is, ‘Well done.’ ”

Weldon, who called himself “the accidental actor” because all he wanted to be was a cabinet-maker, appeared in 12 DCPA Theatre Company productions over 20 years. He won the Colorado Theatre Guild’s 2006 Henry Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor for his work in Gem of the Ocean.

“Charles was an indispensable part of the maturation of the Denver Center Theatre Company,” former Artistic Director Donovan Marley said. “As he did with so many others, Charles changed my life. I cherish him as an artist and as a dear friend.”

When the Denver Center’s Israel Hicks made history as the first director to complete the entire August Wilson canon for one theatre company in 2009, Weldon had been in six of the 10 plays. Weldon often proclaimed Hicks, who died in 2010, to be the best theatre director in America. “You can get somebody who generally knows the plays,” Weldon said. “But you really want to get someone in the trenches who can get his actors to deliver what the words truly mean. That’s what Israel does with August Wilson.”

And Hicks loved Weldon right back, longtime Denver Center Stage Manager Lyle Raper said. “What a team.”

Marley said it stuns him to think that both Hicks and Weldon are now gone. “They changed Denver— especially Denver theater — forever,” he said.

Weldon eventually completed the Wilson cycle himself at various theatres across the country. When he finally got to meet Wilson, called by many “The Black Shakespeare,” Weldon said he told him: “Thank you for my house.”

Harvy Blanks, who performed in eight of the 10 Wilson plays at the Denver Center, was numb from the news of Weldon’s death after having visited him in the hospital just four days earlier. “We were acting up and having fun and now he’s gone,” Blanks said. “I am going to miss him. He was a great actor and a great human being. He was my brother.”

Weldon also had an extensive TV and film career with appearances in “Serpico,” Spike Lee’s “Malcolm X” and “Roots: The Next Generation.” His biggest success was playing Blade in Director Sidney Poitier’s 1980 film “Stir Crazy” starring Pryor and Gene Wilder.

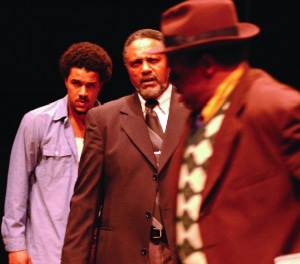

Charles Weldon, center, in ‘Jitney’ in 2002.

In his final project, Weldon starred alongside Nadhege Ptah in an acclaimed, just-released short film called “Paris Blues in Harlem.” She plays a woman desperate to convince her grandfather to sell his insolvent night club. Weldon also appeared this year in the film “Diane,” starring Mary Kay Place and Estelle Parsons.

Weldon served as the Artistic Director of the Negro Ensemble Company from 2005 until his death. That company, which Weldon joined as an actor in 1970, was formed in 1967 to tell original stories with themes based in the black experience. It has been credited with paving the way for writers who came later such as Wilson, Suzan-Lori Parks and others. Last year, Weldon directed the company’s 50th-season revival of Charles Fuller’s racially charged A Soldier’s Play, about a black Army sergeant who cries out, “They still hate you,” into the 1944 night, then is shot dead. Weldon also had appeared in the NEC’s original staging of the play.

“My deepest respect for Charles comes from the profound sense of mission and legacy he felt toward the Negro Ensemble Company, and his dedication – against all odds – to ensuring that it proceeded into the 21st century,” Robert Hooks, one of the company’s three founders, said today. “It takes a lot for one whose true mission is as a performing artist to undertake the daunting task of not only the nuts-and-bolts work of maintaining a company but, in Charles’ case, additionally squaring financial accounts in order to fulfill his dream of prolonging some incarnation of the NEC.”

A most unlikely success story

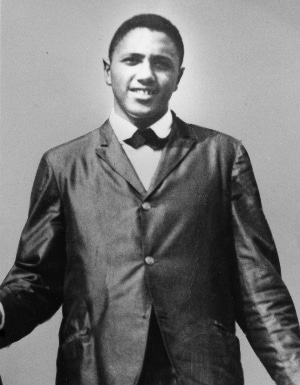

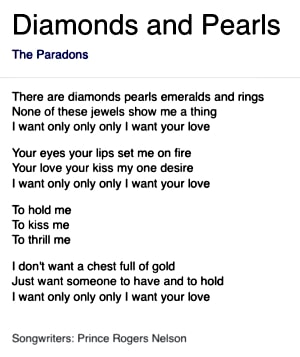

Weldon was born on June 1, 1940, in Wetumka, Okla., to Beatrice Jennings. At age 7, his family moved to Bakersfield, California, where he worked as a teen in nearby cotton fields. At 17, he joined a local doo-wop group called The Paradons. A year later, they had the No. 1 song in the country, the 1960 single “Diamonds and Pearls.” “That was all by luck, you know what I’m saying? Just luck,” Weldon said in a 2013 interview. The band only laid down four songs, but Weldon wasn’t even old enough to sign a contract with a record company at the time, he said.

Charles Weldon as a young

doo-wop singer.

The Paradons quickly dissolved, and Weldon joined a soul group called Blues for Sale as the only black member among five vocalists. But he soon caught the acting bug with help from his sister, actor Ann Weldon. “My sister worked with Bill Ball at the Geary Theater in San Francisco,” Weldon told Glenn Quentin of StageBuddy.Com. “I used to borrow her car. She would be in rehearsals for all these plays, and I used to sit there and wait for her. But I never thought about being an actor. I was just waiting to give her her car back.”

Weldon accepted an offer from playwright Oscar Brown Jr. to perform as an understudy in Big Time Buck White at the Geary. “I ran the lights. I did everything,” he said. “I was like the gopher. That’s where I started learning how to be an actor.”

That job led to a role in the original San Francisco production of the musical Hair at the Geary Theatre. Weldon could not believe it. “I had been an actor for three months and already I was doing Hair,” he said. “We came to work dressed for the show because we were flower children ourselves at that time.” Two months later, Brown called and asked if Weldon wanted to go to Broadway.

“I thought he was talking about North Beach,” Weldon said. “But instead he goes, ‘No, I’m talking about New York. We’re going to take Buck White to Broadway’ – because Mohammed Ali was going to play the lead character. That’s what got me to New York.” The musical closed after only seven performances. Nevertheless, Weldon had made his Broadway debut less than a year after he started acting.

“I thought he was talking about North Beach,” Weldon said. “But instead he goes, ‘No, I’m talking about New York. We’re going to take Buck White to Broadway’ – because Mohammed Ali was going to play the lead character. That’s what got me to New York.” The musical closed after only seven performances. Nevertheless, Weldon had made his Broadway debut less than a year after he started acting.

In 1970, Weldon performed in Joseph Walker’s Ododo for the Negro Ensemble Company. In 1973, he starred in Paul Carter Harrison’s The Great MacDaddy and played Skeeter in Joseph Walker’s The River Niger. Weldon reprised that role in the 1976 film adaptation with James Earl Jones and Cicely Tyson.

Finding success in the 1980 film “Stir Crazy” was double-edged for Weldon, who had three children with first wife Barbara Sotello. That same year he married longtime “All My Children” star Debbi Morgan (she played Angie Baxter), but he was spinning out of control at the time. “I had just made a few movies and was hanging out with Richard Pryor and partying,” Weldon said. He often credited actor Esther Rolle, best known for playing the matriarch on the TV series “Good Times,” for straightening him out. “One time she took me by the collar and looked me in my eye and said, ‘Charles you don’t look good,’ ” he said in the StageBuddy.Com interview. “I laughed, because I thought I looked pretty good. But that stayed in my mind. She told me right to my face, because we were a family. Every time I would lean too far, that voice would come in my head.”

Charles Weldon with family friend Lionel Spears.

But in 1986, Weldon’s best friend of 18 years died, and it sent him spiraling. Adolph Caesar was a gravelly-voiced actor who died of a heart attack on the set of “Tough Guys” just one year after being Oscar-nominated for “A Soldier’s Story.”

“He didn’t have to die,” Weldon said. “But it was a crazy time, and he did die, basically because of all the craziness we were doing.”

Weldon’s wife had left him. He was in the dumps and out of work. He felt what Merle Haggard felt when he wrote “White Line Fever”: “A sickness born down deep within my soul.”

Weldon took a job as a long-haul truck driver from 1986 to 1989. “I didn’t consciously say, ‘I want to go drive a truck,’ ” he said. “I needed a job. Truck driving was what I knew.” And the next three years he spent on the road, he said, were cathartic.

“I knew somewhere inside my psyche that I had to make a change in my life, because I was going off the deep end,” he said. “I didn’t go off and drive a truck because I wanted to be saved — but it saved me. Those months at a time out on that road, by myself, with my own thoughts . . . that saved me because I was not around the things that were taking my life away from me before.”

Weldon’s story inspired much of Mama Hated Diesels, Randal Myler’s musical narrative that tells real stories of those who live, work and sleep in America’s 18-wheelers.

“People have a tendency not to realize when they go to a market that everything in it came from a truck,” said Weldon. “That’s a disconnect for them.”

Weldon never romanticized his life as an actor. “An actor’s job is to get a job,” he liked to say, “because no job lasts forever.” But he probably best summarized his approach to life, of all places, in his Facebook bio:

“I live each day to be honest,” he wrote.

Weldon had four children: Sons Charles “Chucky” Weldon Jr. (Lisa Mapps-Weldon) and the late Nick Weldon; and daughters Barbara Pettie (Jake Pettie Jr.) and Terri Hamilton. He is also survived by 10 grandchildren. Charles Weldon Jr. said a life celebration will be planned in the new year.

Charles Weldon, right, in ‘Radio Golf’ in 2009.

Charles Weldon/DCPA Theatre Company

Charles Weldon/Additional career highlights:

Charles Weldon reunited with ‘Malcolm X’ castmate Denzel Washington in 2016.

Film:

Television:

Additional Theatre:

From left, Cecilia Antoinette, Jay Ward, Charles Weldon and Chauncey DeLeon Gilbert in the Negro Ensemble Company’s 2016 revival of ‘Day of Absence.’ Weldon played the Mayor. Photo by Jonathan Slaff for the NEC.