DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

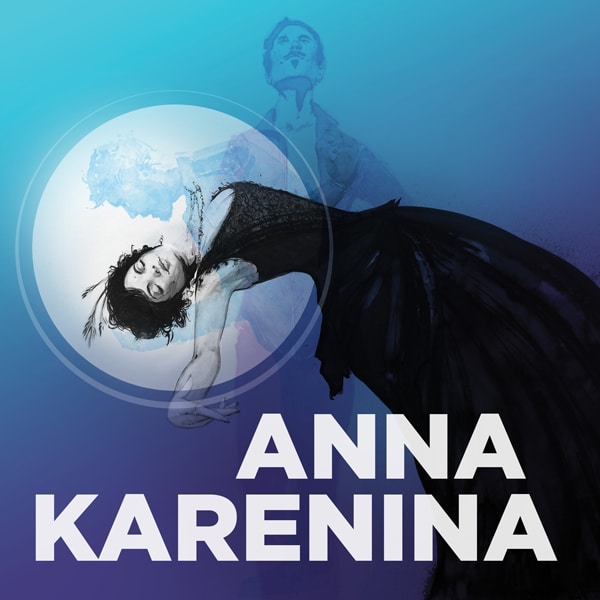

Allison Altman, Kyle Cameron and Patrick Zeller in rehearsal for ‘Anna Karenina.’ Photo by John Moore.

Is it possible to squeeze a roughly thousand-page novel into less than three hours on stage? Not easily. Ask anyone who’s tried and failed.

Or do as I did: ask Chris Coleman, the DCPA Theatre Company’s Artistic Director, who recognized that the huge but complicated potential of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina might be worth the effort — and did something about it.

Early in this century, Coleman had helped Kevin McKeon, a member of Seattle’s Book-It Repertory Theatre, with an adaptation of David Guterson’s Snow Falling on Cedars that Coleman was mounting in a second production at Portland Center Stage, where he was the Artistic Director at the time.

“Kevin managed to take a very complex — and long — story and condense it into something that felt taut, suspenseful, muscular and poetic,” Coleman said. “I loved how he boiled things down. It was impressive.” So impressive that Coleman suggested to McKeon that he might like to consider tackling an adaption of Anna Karenina.

Patrick Zeller and Kate MacCluggage in rehearsal as Count Vronsky and Anna Karenina. Photo by John Moore

McKeon hadn’t even read the novel. But, as he told an interviewer at the time, “it loomed as a challenge and that’s what hooked me.”

The project took roughly two years to complete, emerging as a hit with Portland audiences when Center Stage held its world premiere in 2012.

“Thinking about the flow of my first season in Denver,” Coleman wrote, “I wanted a big, classic story in The Stage Theatre. I considered Shakespeare, but felt it might be a bit obvious. I also noted that adaptations of literature had resonated well with [Denver] audiences.

“I’ve been involved in several conversions from page to stage. I love the challenge of translating between mediums. I’ve directed several Chekhov productions, and two Dostoyevskys over the years — and love the wild world of pre-revolutionary Russia. I also knew that, besides being a multi-layered love story, Anna K would offer a sweeping epic treatment that could be very dynamic.”

It was Oprah Winfrey, Coleman said, who introduced him to “the beautiful translation of Anna Karenina by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky that came out about a decade ago.

“I was surprised by what a page-turner it was. So layered and complex. A feast. Definitely on my list of all time greats.”

Shaping the introspection and sheer volume of Anna Karenina into a functional play, however, forced adapter McKeon to seek and find a looser approach with the writing. That never meant playing around with the central story — that of Anna, a St. Petersburg socialite, married to a prominent government official and swept off her feet by Count Vronsky, a handsome, well-to-do Cavalry Officer. Their passionate affair drastically altered their lives and ended badly. That remains unchanged.

So does a parallel plot involving Constantin Levin, a liberal landowner and old friend of Anna’s brother. Levin’s well-meaning but lame efforts at a back-to-the-land existence include clumsy attempts at democratizing the handling of serfs on his estate. Aside from counterbalancing the love story, his tale makes room for Tolstoy to offer some of his own complex views on nothing less than faith, politics and the meaning of life.

“Levin and Anna … That is a huge one, isn’t it?” Coleman said. “My first impulse is that they might somehow express two different aspects of Tolstoy’s own psyche. He had a very robust and adventurous sex life when he was a young man. The tension that created with the philosopher/social change agent within him likely fueled much of his writing in some way.”

The stage adaptation of Anna that McKeon finally achieved doesn’t attempt to replicate Tolstoy’s dense, detailed and emotional language. Too novelistic. He needed to find a way to interweave the parallel stories concisely, and he eventually settled on a technique created by Paul Sills in his 1970 play called Story Theatre, wherein the characters on stage take on the speaking of the narrative as well as the dialogue.

This greatly tightens the connective tissue, allowing scenes to flow smoothly one into the next. By using such “theatrical shorthand,” McKeon, who’s an actor and director as well as a writer, compressed long stretches of narrative into fewer lines, while retaining a bracing vitality.

“What is interesting about Tolstoy’s journey with the story,” Coleman said, “is what he thought he was setting out to write, and what he ended up writing. As someone born to enormous privilege, who spent his life trying to upend the social and spiritual status quo, it seems he began thinking he would be condemning the infidelity that leads to Anna’s downfall.

Casting: Anna Karenina brings Kate MacCluggage back to Denver Center

“But the farther he walked on the journey, the deeper his personal involvement in the individual psyches involved, and the poet in him took over. The facets are so various, it’s hard to decide where he landed or if he landed in one place, morally. It was revolutionary that he took this very complex love story and used it as a motor around which he could take on all the major debates and boiling points of the day.”

Denver’s Anna Karenina has a cast of 20 actors, all of them new to the play and to this entirely new production.

“There is no way to replicate the intimacy of the experience of actually reading a novel when you translate it to the stage,” Coleman acquiesced in parting, “but you do gain visual style, tension, action and forward momentum. The trick is making place for the narrative voice and not letting that voice deflate the forward motion.

“It’s a dance.”

Sylvie Drake is a translator, writer, and a former theatre critic and columnist for the Los Angeles Times. She is an occasional contributor to American Theatre magazine and the Los Angeles Times, and regular contributor to culturalweekly.com. She also served for several years as Director of Publications for the DCPA.

The cast and crew of ‘Anna Karenina.’ Photo by John Moore

Go to our complete photo gallery on the making of Anna Karenina

With the lavish grandeur of Imperial Russian fashion as his inspiration, Anna Karenina Costume Designer Jeff Cone had his work cut out for him.

“Period costumes, while more intricate and time-intensive, are also much more fun and interesting to design,” says Cone in an interview with Portland Center Stage. Intricate and time-intensive, indeed. Late-19th century fashions in Saint Petersburg were embellished with fur, embroidery, and ornate decorations such as pearls and jewels. At least, that’s what the upper class was wearing.

A parallel story to Anna’s tragic romance is that of Konstantin Levin, a wealthy country landowner who wrestles internally with the class disparities he witnesses around him.

“The people who we spend the most time with in this production are in the top 0.5 percent of the economic ladder of that world,” said Director Chris Coleman. “So when we see the more humble people in that world, it’s a sharp contrast.”

As for how to fit 83 costumes into a two-act play with 17 actors that moves at a cinematic clip, Cone hopes you won’t notice at all. “When the actors become their characters, their dress becomes a part of them and their performance. A great costume shouldn’t draw attention away from that performance. If the costumes aren’t noticed, we’ve done our job.”