DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

In Hotter Than Egypt, playwright Yussef El Guindi explores the tragic-funny misunderstandings of a culture clash rich in existential, social, political baggage.

Yussef El Guindi

While on holiday in Egypt, middle-aged Americans Paul and Jean find their marriage unraveling in the company of a young couple, Seif and Maha, who serve as their guides and conscience. Cut off from routine, conflicts and intrigues surface that cause everyone to confront harsh, yet humorous truths.

After a well-received 2020 Colorado New Play Summit staged reading, Egypt is back at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts with a fully staged production.

“I was blessed with a great cast and director. [DCPA Theatre Company Artistic Director] Chris Coleman shepherded the first workshop, so it’s gratifying to have it return for a full production under his direction,” said El Guindi.

Born into a family of notable creatives in Egypt, El Guindi studied in the United Kingdom and America, where he eventually settled. The award-winning playwright’s first passion was acting.

“I applied to six acting programs and one program for playwriting. All six acting schools rejected me, while Carnegie Mellon accepted me into their playwriting program. So, basically, I’ve been living Plan B. But I also never let go of my desire to become an actor.”

Chris Coleman and Yussef El Guindi rehearsing Hotter Than Egypt for the 2020 Colorado New Play Summit. Photo by John Moore

He worked in theatres in San Francisco, then got a job teaching playwriting and a dramatic literature class at Duke University. But he still pursued an acting career after landing in Seattle, where he resides.

He was in his late 30s when he finally gave up on acting and fully committed to playwriting. Seattle’s ACT Theatre became his creative home.

“Having a place receptive to my work and more than willing to consider it for production is vital. It prompts me to write the next play. And for that I am enormously grateful. Having ACT in my corner is a great boon. Such support is essential for me as a playwright.”

His work interrogates the fraught Arab-Muslim experience in America.

“Part of the impetus in telling these stories is to counter the sometimes horrendous reductiveness of mainstream depictions of Arabs and Muslims,” he said. “Rather than some agenda-driven goal in writing these plays, it’s really just about presenting fully-formed Arab-Muslim characters in different kinds of stories – and not as plot points in flattened narratives about the religion or cultures.

“Part of the impetus in telling these stories is to counter the sometimes horrendous reductiveness of mainstream depictions of Arabs and Muslims,” he said. “Rather than some agenda-driven goal in writing these plays, it’s really just about presenting fully-formed Arab-Muslim characters in different kinds of stories – and not as plot points in flattened narratives about the religion or cultures.

“Presenting them as regular folk in varied storylines becomes a radical act all by itself.”

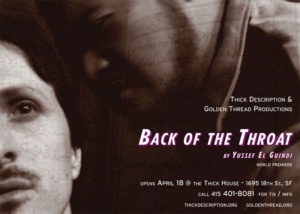

His Back of the Throat (2005) deals with Arab-American fears in the post-9/11 environment.

As members of ignored or demonized populations push back on negative narratives by telling their own stories, he said, “these formerly marginalized groups very slowly and painfully become a tiny bit more integrated into the mainstream cultural life.”

His chosen form for sussing out truth: farce.

Kirsten Potter and Gareth Saxe in the Hotter Than Egypt staged reading

“I was very taken by farce very early on. The manic and merciless quality of the genre appealed to my youthful writer self wanting to get a rise out of the audience.

There’s nothing like laughter to plug an audience into a moment, and the play as a whole, hopefully. It’s also very gratifying as a writer to hear that laughter. But farce is also very close to tragedy in its unrelenting propulsion towards inevitable ends. In both farce and tragedy we are pawns to forces greater than ourselves. We feel powerless at times, in our attempt to be agents in our own destinies.”

The vagaries of leaving one culture for another make fertile ground for farce.

“You come to a new country and have to adjust to the way it operates, while also letting go of some of the protocols, manners and values of the country you were raised in. The larger the leap. The bigger the adjustment,” he said.

In the wash, misunderstandings occur. “A stranger in a strange land becomes a potential source of comedy as the character tries to figure out what’s what,” El Guindi said. Hotter Than Egypt’s protagonists stumble about in the mess they make, negotiating new definitions of their relationships, power dynamics and selves.

“Everyone,” he said, “has a moment where they break things down and offer their opinion or analysis.” In Hotter Than Egypt:

What’s meant to be a vacation from reality turns into a crucible of open wounds and greener pastures.

Gareth Saxe and Kirsten Potter in the Hotter Than Egypt staged reading. Photo by John Moore

“There is some truth to the feeling there is surely a better alternative ‘over there,’ whether a place or a person, if you could just make it happen. Shorn from old habits and rituals, we are a little lost on holidays, sometimes wonderfully so, and in that in-between place we are able to gain the kind of perspectives hard to come by in our regulated lives back home.

“The sin sometimes is to feel one is absolutely right and the other person is wrong or on much shakier ground than you.” As a cross-cultural wayfarer himself, El Guindi draws on personal experience for these crises of identity and longing. His milieu is his material.

His advice to new playwrights is to “endure” in finding their own voice.

“Stay at it, practice your craft – which means finding ways to hearing your plays read by others. You’ll only learn in the doing. Make the needed adjustments with each reading-staging. Find like-minded theatre practitioners and work with them. Don’t wait for the big theatres to legitimize you. Be a self-starter and make things happen for yourself.”

Playwriting groups are another way to connect. “It’s lovely having this community out there.”

DETAILS

Hotter Than Egypt

Feb 10 – Mar 12 · Kilstrom Theatre

Tickets