DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

On Saturday, April 16, 2022, Denver Mayor Michael Hancock gave an official apology — for something that happened in 1880.

The Chinatown Riot

He apologized for the anti-Chinese race riot of October 31, 1880 known as The Chinatown Riot. The event destroyed much of what had been a thriving Chinatown district in what is today the thriving entertainment district we know as LoDo, or Lower Downtown. Denver is the first city outside of California to offer such an official apology, and the only city that has a small percentage of Chinese. Other apologies were in cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Jose, which have much larger Chinese and Asian American populations. Mayor Hancock acknowledged the 1880 anti-Chinese riot, but also the more than a century of anti-Asian hate that has come since, including the imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II and the past few years of anti-Asian hate crimes.

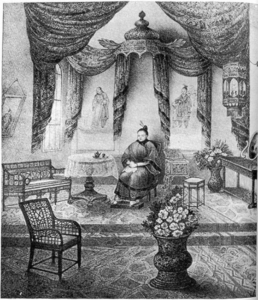

The DCPA Theatre Company’s production of The Chinese Lady (Sept 8-Oct 16, 2022) cites the 1880 riot in its historical overview of the Chinese American experience since the 1834 arrival of 14-year-old Afong Moy. She was brought here originally to demonstrate Chinese customs in order to drum up interest in foreign imports and later, toured the country as a curiosity for paying audiences to gawk at.

Afong Moy came alone to America, but the first wave of Chinese immigrants arrived after 1849 to take advantage of the gold rush in San Francisco, hoping to strike it rich in “Gold Mountain,” as they called the country. But they faced racism and found laws were enacted to prevent from owning gold mines. They could only work for white mine owners, and even then, they were often chased out by gangs. Up and down California, a spate of racial riots destroyed Chinese immigrant encampments. Many Chinese chose other jobs: domestic servants, running restaurants and shops for the established Chinatowns that had taken root, or becoming a laborer on the Transcontinental Railroad.

Afong Moy

Up to 12,000 Chinese worked on the Transcontinental Railroad, and about 1,200 died because they were given the dangerous work of blasting tunnels through mountains. A hundred railroad workers — mostly Chinese — died in an avalanche in the Sierra Nevada mountains. When the “Golden Spike” ceremony was held to commemorate the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869, the Chinese laborers were told to stay away and are not in any of the photographs that captured the event. That is one reason that Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month is held in May every year.

Once the railroad was completed, Chinese began looking for work by taking the railroad south from Wyoming into Colorado. They found work in Colorado’s mines, and some found their way to the neighborhood in front of Union Station. Throughout the 1870s, the Chinatown district was established and grew, with businesses and residences rooted along the streets and alleys between 15th and 17th streets, and Blake and Market.

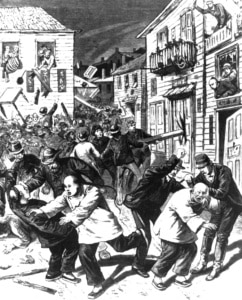

On October 31, 1880, a fight broke out between four white men and two Chinese in a pool hall, which spilled out into the streets. Within a few hours, years of pent-up racial hatred led to thousands of whites converging on Chinatown, destroying businesses and chasing out the Chinese. One man, Look Young, was beaten to death and hung from a lamp post at 19th and Arapahoe. Several white business owners including a madam took in the fleeing Chinese and protected them. Even though this was an anti-Chinese riot, it was used as a reason why Chinese should be banned from the United States. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which to this day is the only immigration ban to name a country of origin.

(L to R) Aisha Rousseau, City of Denver’s chief equity officer; Mayor Michael Hancock; William Wei; Linda Lung, descendant of residents of Denver’s Chinatown. Photo by Rocky Mountain PBS

The Chinese returned to the area, and vestiges of their legacy were still on view into the 20th century. A Chinese Masonic Lodge had a building on Blake Street and held parades into the 1920s. An “American Chinese Association” (note that American is emphasized first) was headquartered on Larimer Street across from what is today Sakura Square, the heart of the Japanese Community, well into the 1850s. The only remnant of the riot for many years has been a plaque on a building across from Coors Field misleadingly titled “Hop Alley/Chinese Riot of 1880,” which gives the impression that the Chinese rioted instead of being the victims and emphasizes the opium dens, which had been a racist name for the area. The plaque also names the white business owners who rescued fleeing Chinese, yet doesn’t name the murdered man, Look Young.

Today, most Chinese in the Denver area are recent immigrants from China, Taiwan or Vietnam. That is, except two families who are descendants of Chinatown business owners. Mayor Hancock greeted them in his April ceremony and gave them special plaques of apology.

And on August 8, thanks to the efforts of Mayor Hancock’s office, Colorado Asian Pacific United (CAPU), an ad-hoc organization formed last year to commemorate the legacy of Chinatown and which led to the city’s apology, oversaw the removal of the inaccurate plaque about the 1880 anti-Chinese race riot. It was the first step in a campaign to erect other, more accurate historical markers and eventually, an Asian American Pacific Islander Museum in LoDo.

It’s taken many decades, but the Chinese immigrant story started by individuals such as Afong Moy, “The Chinese Lady,” is finally being remembered.