DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

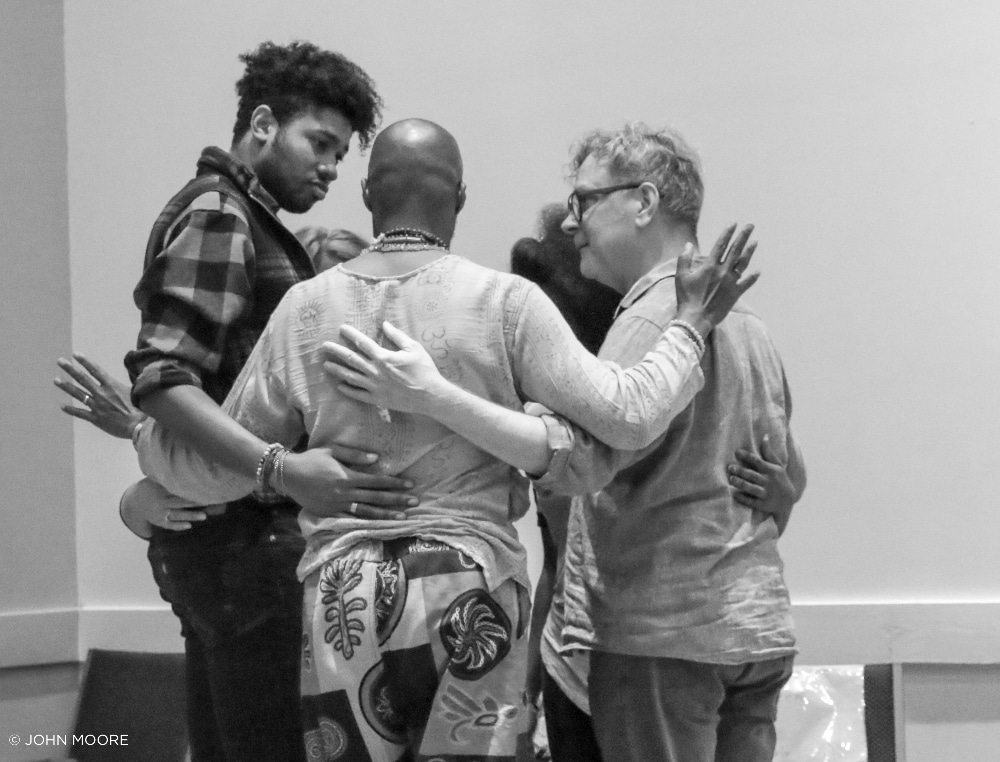

Clockwise from left: Actors Saxton Jay Walker, Emma Messenger, Ilasiea Gray, Gary Norman, Assistant Director Kristen Adele Calhoun and Playwright Rodney Hicks. Photo by John Moore.

It’s not easy for the actors to say the things they have to say in Flame Broiled. or the ugly play, a series of fast-paced vignettes that look at race in America through a series of 15 comic and unsettling snapshots. Like when a white woman wonders, “Why do they hate us?” with callous obliviousness. Or when a white actor says the “n” word to a black castmate in a misguided attempt at racial solidarity.

“Some of the material we were given is really explosive and sort of dangerous,” said actor Gary Norman.

Photo by Michael Ensminger.

But do it, they must, director and playwright Rodney Hicks says, “because you’ve got to get through the ugly to get to the joy.”

On first day of rehearsal for Local Theater Company’s incendiary world-premiere play, Hicks told his four actors (two white, two black) that this would be unlike any creative process they’ve been through before. But he assured them they were in a very safe space.

“We created love in the room,” said Hicks, who performed in the original Broadway casts of Rent, The Scottsboro Boys and Come from Away. And that’s exactly what he hopes to create every night his play is performed from October 24 through November 17 at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder.

“Rodney really created a room for us that was a launching pad of safety,” said actor Saxton Jay Walker. Multiple award-winning castmate Emma Messenger said she felt a kind of instant grace in the rehearsal room. “Everybody just came with their hearts open,” she said. “But at the same time, we were often reminded that this is called the ugly play, and not to be afraid to get ugly at times. You don’t do the play justice if you can’t go there, too.”

Added Walker: “I feel like for this play, you’ve got to expose yourself to know thyself.”

The rehearsal process included meditation, sharing personal stories and intimate bonding exercises. “And there was dancing,” said Hicks. Which is unusual considering this is not a musical. It all required complete buy-in from every member of the cast and crew.

“These people are rock stars,” Hicks said.

‘You’ve got to get through the ugly to get to the joy.” – Rodney Hicks

Flame Broiled, which has grown out of Local Theater Company’s acclaimed Local Lab new-play development festival, takes the audience through a series of touchy racial subjects that spark the kind of onstage dialogue we all need to be having in this era of racial profiling, police shootings, social unrest and the underlying economic disparity that continues to fuel it.

Hicks’ fast-paced, 80-minute play shifts in tone with wild intention. It introduces 34 characters, starting with two feuding women in (apropos of the play’s title) a fast-food drive-through. In it, an angry black woman has intentionally driven to the white part of town to be served by an (equally angry) white woman. The play presents a “Saturday Night Live” game-show parody one minute and is talking about Emmett Till, lynchings and blackface the next. It explores interracial relationships, abortions and black queerness. At its most poignant, it shows two young girls, one black and the other white, sweetly incapable of understanding why they can’t be playmates.

So Flame Broiled is sketch comedy. It’s satire. It’s political. It’s drama. It’s tragedy. All of which makes it something of an unclassifiable theatrical Rubik’s Cube. Hicks calls it the equivalent of channel surfing: “You get everything,” he said, “and it all moves very fast.”

Rehearsal for ‘Flame Broiled,’ from left: Saxton Jay Walker and Gary Norman. Photo by Nick Chase

Walker calls the play “a campfire for everyone to come sit around. It’s burning bright – and if you get too close to the fire, it’s going to make your eyebrows fall off.”

True West Award-winning actor Ilasiea Gray likens the theatergoing experience to gathering around the TV with friends to watch high-stakes, fast-paced Super Bowl commercials. “You only have that 60-second spot to make your point and then it’s on to the next,” Gray said. “You don’t have much time to settle in with something that makes you uncomfortable, because we’re moving on.”

Assistant Director Kristen Adele Calhoun says it is the play’s originality that makes it so difficult to describe. “It stands on the shoulders of George C. Wolfe’s play The Colored Museum,” she said. “It stands on August Wilson’s work, and it stands on Suzan-Lori Parks’ work. But even the form of it is original, so I would just tell people to come and experience it for themselves.”

If they do, they will be given the opportunity to sit in a darkened theatre with a roomful of strangers and sync up their heartbeats with people they might not otherwise ever cross paths with. “I think people are going to see themselves on stage doing things they didn’t even realize are offensive,” Calhoun said. “I’m excited for people to come out and be challenged – and also to feel like there’s hope.”

Messenger says the play is less a call to action than a call to listen. Says Gray: “Give yourself a break, because it’s easy to beat yourself up. This play is an opportunity to re-evaluate, to re-examine and move forward in the world a little bit differently.

“Just be better.”

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theater critics in the U.S. by American Theatre Magazine in 2011. He has since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center’s Senior Arts Journalist.

Photos by John Moore.

‘Flame Broiled’ rehearsal. Photo by John Moore.