DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

In this daily five-part series for the DCPA NewsCenter, we introduce you to the plays and playwrights featured at the Denver Center’s 2020 Colorado New Play Summit through February 23. Over the past 15 years, 31 Summit plays have gone on to be premiered as fully staged productions on the DCPA Theatre Company’s mainstage season. Today: Suzan Shown Harjo and Mary Kathryn Nagle, co-authors of ‘Reclaiming One Star.”

Suzan Shown Harjo, left, and Mary Kathryn Nagle

The play in a nutshell: The truth proves stranger than fiction in the story behind the racist name of the football franchise the Washington R*dsk*ns (vowels omitted at the request of the playwrights). Team owners have long maintained that the name honors Native Americans because it pays homage to an early coach, allegedly a “full-blooded Sioux.” But when Tony One Star sets out to uncover the facts behind his granduncle’s life and mysterious death, he shatters the myth behind the mascot. Equal parts detective thriller and courtroom drama, this DCPA Theatre Company commission gives an inside look at the real-life legal intrigue behind this multifaceted case, including perspectives of attorneys defending the team’s name and the people they want to keep quiet about the slur.

The playwrights at a glance: Suzan Shown Harjo, of Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee heritage, is a lifelong advocate for American Indian rights and in 2014 was conferred the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest U.S. civilian honor, by Barack Obama. She is a poet, writer, lecturer, curator and grandmother who has helped Native peoples recover more than 1 million acres of tribal lands. After co-producing the first Indian news show in the nation for WBAI radio in New York City, she moved to Washington, D.C., in 1994 to work on national policy issues. She served as Congressional liaison for Indian affairs under President Jimmy Carter and later as president of the National Council of American Indians. Her plays include co-writing My Father’s Bones. Co-writer Mary Kathryn Nagle is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation. She is also a partner at Pipestem Law, P.C., where she works to protect tribal sovereignty and the inherent right of Indian Nations to protect their women and children from domestic violence and sexual assault. She is an alumna of the 2013 Public Theater Emerging Writers Program, with plays including Miss Lead, Traceable, Sovereignty and Manahattan.

“R*dsk*ns is a word that really should be right up there with the N-word in peoples’ consciousness.” – Suzan Shown Harjo

The fight over the name of Washington’s professional football franchise has been waged for nearly 90 years, with no end in sight. It’s an issue mired in memories, money and a misguided sense of honor. But to playwright and attorney Mary Kathryn Nagle, it’s an open-and-shut case of racial and cultural appropriation.

“Non-Native Americans do not own Native identity,” she said. “We are not the property of non-Native Americans. And our identity is not for sale, period.”

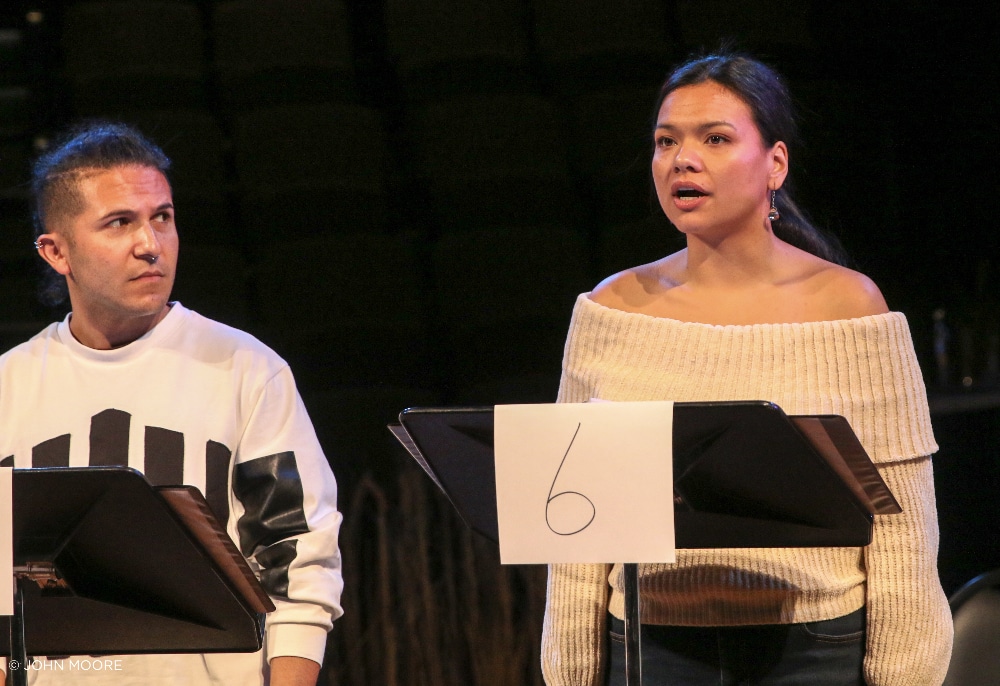

Nathalie Standingcloud in rehearsal for ‘Reclaiming One Star.’ Colorado New Play Summit. Photo by John Moore

Suzan Shown Harjo has been working to eliminate 6,000 racist mascots from elementary schools, high schools, colleges and professional sports teams since 1962. In that time, she has succeeded in having two-thirds of them dropped, including St. John’s University’s change from the Redmen to the Red Storm. Closer to home, she pitched in on the effort to convince Arvada High School to change its nickname from R*dsk*ns to Reds in 1993, and its mascot from an Indian to a bulldog.

Nagle and Harjo have argued their case in courtrooms and at rallies for decades. Now they are taking their story to the stage as commissioned playwrights of the DCPA Theatre Company. Their new play Reclaiming One Star tells a gripping, real story of stolen identity in a theatre, a setting much more conducive to reaching people than a courtroom.

“There’s just something different about a theatre,” Harjo said. You listen in a different way. Theatre is like music. You hear it in a different part of your brain. You hear it in your heart.”

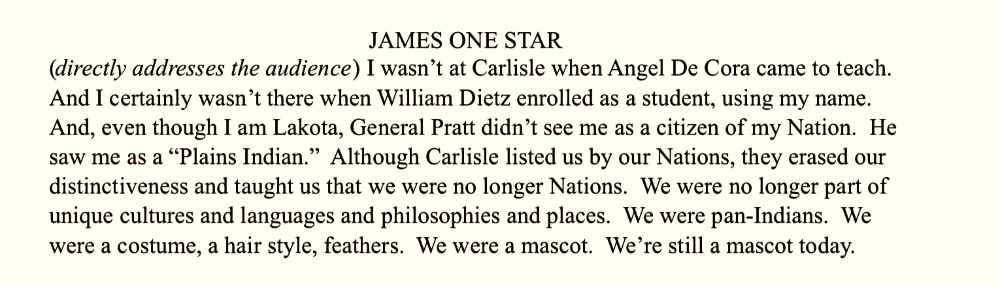

Those who come to Reclaiming One Star will learn the shocking story of William ‘Lone Star’ Dietz, who was the football franchise’s first coach in 1932. Dietz was a man of contested heritage who claimed to be a full-blooded Sioux. But back in 1919 he was sent to jail for fraudulently attempting to steal the identity of a young man named James One Star so he could play on a Native American football team coached by the legendary Pop Warner. “But he was not only stealing James’ identity,” Nagle said, “he tried to steal his family, his land, his money – everything.” (More on that below.)

“Our play reclaims James’ identity, which is still being appropriated in a very wrongful manner by the Washington football team today.”

Nagle and Harjo are both based in Washington D.C., and while Nagle has been in Denver for the past two weeks preparing their script for its featured presentation at the 2020 Colorado New Play Summit, Harjo is back in Washington fueling a revived national effort to bring the issue of racist mascot names back to the fore.

Read the study about Native identification and opposition to mascots

The effort had suffered a massive setback back in 2002, when a Peter Harris Research poll claimed that 81 percent of American Indians are not offended by Native American symbolism in sports. But just this month, a major new study by the University of California Berkeley and the University of Michigan debunked that study as flawed. It offered peer-reviewed research that instead claims stereotypical Native mascots are indeed dehumanizing to Native Americans, and are especially damaging to the self-esteem of its youth.

“This new research is critical to understanding what actual Native peoples think about sports mascoting and how we are harmed when our identities and cultures are exploited by the NFL and other profiteers,” said Harjo, who is feeling a burst of renewed energy around the issue, fueled in part by Maine becoming the first state to prohibit schools from using Native American symbols as mascots, and this weekend’s unveiling of Reclaiming One Star at the Colorado New Play Summit. The cast includes Wes Studi, who just became the first Native American to receive an Academy Award for acting, and his accomplished niece DeLanna Studi.

“We and myriad allies have consigned more than two-thirds of objectionable ‘Native’ mascots to history books because educators, journalists, politicians and social-justice leaders have listened and learned about how mascots hurt our children,” Harjo said. “The time has come for the NFL to stop mocking, start listening and end this public bigotry.”

Leigh Miller, center, plays football owner William ‘Lone Star’ Dietz in ‘Reclaiming One Star.’ Also pictured are Timothy McCracken and DeLanna Studi. Photo by John Moore.

At the heart of the conflict is identity vs. nostalgia. Team owner Daniel Snyder says George Preston Marshall chose the name in 1933 to honor coach Dietz, four Native American players on his team – and Native Americans in general. He also argued sports mascots become deeply tied to a team’s identity and its community over time, and that changing the nickname would lessen his fans’ long-term memories of the team.

“We’ll never change the name. It’s that simple. NEVER. — And you can use caps.” – Washington owner Dan Snyder to USA Today

In 2013, a group of 61 religious leaders in Washington D.C., sent a letter to Snyder and NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell stating their moral obligation to the R*dsk*ns name simply because it causes pain – whether or not that pain is intended. Snyder responded by telling USA Today: “We’ll never change the name. It’s that simple. NEVER. — And you can use caps.”

The irony, Harjo said, is that if the football team were to change the name, not only would that be seen by many as an act of goodwill, the team would stand to make a lot of money – because every fan would then need to buy a new jersey.

“That is absolutely right,” Harjo said. “And we made that argument over and over and over again.”

Case in point: Abe Pollin, the owner of Washington’s professional basketball team, changed the team’s name from Bullets to Wizards in 1995 because the name had started to take on violent overtones that made him increasingly uncomfortable given the rising homicide rate in D.C. at the time. Pollin, who died in 2009, urged Snyder to follow suit.

“Abe Pollin told Daniel Snyder: ‘I guarantee you, if you do this, you can be a hero. Everyone will still love the game, and you will make a fortune off the sale of new memorabilia.’ ” Harjo sad. “But Snyder was adamant. Because it’s not about money to him. It’s not about the tradition of it. It’s about power, and how power makes certain people feel who go into the field of big-league sports.”

“What really has to happen is the American public has to stop tolerating it.” – Mary Kathryn Nagle

But Nagle says she will never lose hope that Snyder, in her words, “might start to see us as humans someday. He’s human, and I think the human heart is capable of opening and reconsidering these things. I do think it is probably more likely that it will be the next generation of folks in power that will make that change. But we will never give up.”

Being both activists and playwrights, Harjo and Nagle hope audiences see their new play as a call to action. “We humbly ask the American public to stand with us in advocating for the change of the Washington football team name to help make it clear to all people everywhere that the use of racist mascot names must end,” Harjo said.

Added Nagle: “What really has to happen is the American public has to stop tolerating it. Right now, Americans do not care. But if all Americans started saying, ‘I’m not going to watch Washington football games; I’m not going to buy their merchandise; I’m going to have nothing to do with that team because its name is immoral, and I don’t want to support dehumanizing Native people,’ then I think Dan Snyder would change his mind. Because that would cost him.”

Here are excerpted highlights from more of Senior Arts Journalist John Moore’s conversation with Suzan Shown Harjo and Mary Kathryn Nagle:

John Moore: In your script, you write the name of the Washington football team as R*dsk*ns. Tell me why it is important to you that I not use vowels myself when typing that word.

Suzan Shown Harjo: We ask that to call attention to that as a word that really should be right up there with the N-word in peoples’ consciousness. That is not a word that should be permissible in polite society. That is very important to us.

John Moore: Tell us what happens in your play.

Mary Kathryn Nagle: The play opens in 1889 and runs through 1920. The story uncovers the truth behind the lies the Washington football team has told, and specifically Dan Snyder, regarding why they decided to name their team the R-word in the first place. William “Lone Star” Dietz was actually investigated by the FBI and prosecuted by the United States Attorney and went to jail for fraudulently attempting to steal the identity of James One Star.

John Moore: Tell me more about James One Star.

Mary Kathryn Nagle: He was forcibly removed from his home om the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in 1889, as so many children were at that time. They were taken from their homes within their tribal communities and brought to the Carlisle Indian School that was created and run by Richard Henry Pratt, the U.S. military and the War Department. James One Star’s story is tragic, as are the stories of all Native children who were kidnapped from their homes and taken to Carlisle. James One Star joined the military, fought in Cuba and died fighting for the U.S. Army. And the school, and Richard Henry Pratt, and everyone associated with the Carlisle institution, never told his family exactly what happened to him. This was at a time when the Carlisle Indians football team was one of the best in the country, and the coach that time, Pop Warner, was recruiting anyone, whether he was Indian or not. They could do that because they created these false identities to make them ringers on the football team. It was all about the football team. So when Pop Warner recruited William Dietz to play for Carlisle, they somehow discovered that they could just steal James One Star’s identity and gave it to William Dietz. They gave him his enrollment papers. Dietz is obviously not native, so he could not have enrolled in a school like Carlisle and play on the football team otherwise. And not only that, William Dietz also started writing letters to James’ sister, Sally. He told her: “I’m still alive … can you send me my government annuity check? Can you send me the papers to my allotment lands?”

John Moore: Sounds like a heck of a play.

Suzan Shown Harjo: We hope so.

Read the full history of the Washington mascot naming controversy

John Moore: So how did it come to be a Denver Center Theatre Company commission?

Mary Kathryn Nagle: Suzan and I have been talking about writing this play for years. We had pitched the idea to many different theaters, but no one showed any interest. So when [Artistic Director] Chris Coleman reached out to commission me to write a new play for the DCPA Theatre Company, I told him, “I have been dreaming of writing this play with Suzan Shown Harjo. Can we work it out so that both of us write this play together? And could the Denver Center be its artistic home?” And Chris said, “That sounds fascinating. Absolutely.” He has been very supportive of us both from Day 1.

John Moore: Suzan, what does it mean to you that the Denver Center has given you this platform to tell your story?

Suzan Shown Harjo: Well, it means everything. We feel so warmly received and so surrounded by support. I think it’s just marvelous.

John Moore: Tell me more about your involvement with the Arvada High School mascot controversy.

Suzan Shown Harjo: My old friend Vernon Bellecourt, a prominent leader in the American Indian Movement at the time, took the lead on that, and I was happy to pitch in. He talked to the principal there several times asking him to make the change. And he told us, “Did you know this had nothing to do with Native Americans when the team started? It was started because our colors were cherry and white, and a beloved coach there – [Side note: There’s always a ‘beloved coach’] – bought the players cherry-colored jerseys. But it rained during the game the first time they wore them and the ink ran through. So when they took the jerseys off, their skins were dyed cherry colored. So they decided to call themselves “R*dsk*ns” – because now they had red skin. I was speechless when I heard that. But I don’t think the principal was lying. I just don’t think he had ever questioned himself about that story. My question for him was, “Then what are those feathers about? And the Indian mascot?”

John Moore: So they changed the name from R*dsk*ns to Reds.

Suzan Shown Harjo: They did:

John Moore: But how is “Reds” any better than “R*dsk*ns”?

Suzan Shown Harjo: It’s a lot better. It’s not the red that’s offensive. What’s offensive is the skinning of our people for bounty pay. Colonies, and companies and later whole states issued bounties for dead Indians. And they skinned us. They actually took our skin and our body parts into the bounty payers to collect their blood money. The scalps were the proof of dead Indians they needed. Sixty cents for men, 40 cents for women, 20 cents for children. Now, how do you know the age and the gender without scalping the private parts of the person? That’s the horror, and that’s the nightmare that’s called up for Native people when we hear that term.

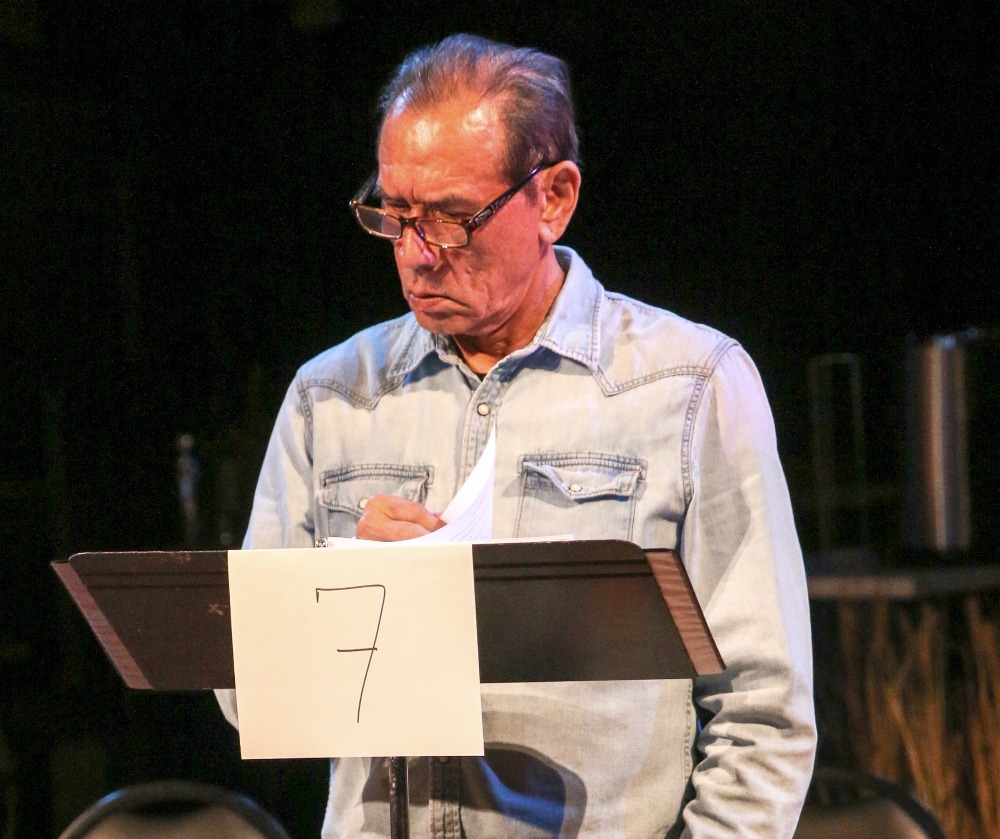

Wes Studi in rehearsal for ‘Reclaiming One Star.’ Photo by John Moore.

John Moore: And what is your response to Snyder’s argument that the name R*dsk*ns is intended to honor Native American peoples?

Mary Kathryn Nagle: I would say, “Why do we need to even perpetuate that?” I think a lot of Americans would say, “Actually, we don’t need to perpetuate that. Let’s not dehumanize one group of people, especially the first people who ever lived here on this land. That’s very disrespectful and horrible.”

John Moore: What does it mean to you that Wes Studi and his niece, DeLanna Studi, are lending not only their talents but their names to the visibility of this project?

Suzan Shown Harjo: They both have always been advocates for Native rights. Always. DeLanna has her own one-woman play about this issue. And Wes has been an activist for a very long time.

John Moore: What do you want people thinking about when they leave the play?

Suzan Shown Harjo: I want them thinking that James One Star was wronged, and that his identity was stolen. His identity was commodified for other people’s entertainment and recreation. His own identity, his real identity, was erased from history. And that makes it very personal for us.

Mary Kathryn Nagle: That new study found that in 87 percent of schools grades Kindergarten through 12 don’t teach students about any Native Americans after 1900. We are that romantic, noble savage that William Dietz was able to erase. We don’t otherwise exist today in America except as a racist mascot.

Suzan Shown Harjo: It makes us ask ourselves, “Are we alive? Are we present? Are we humans? A lot of people think we’re long dead, gone, buried and forgotten. Well, here we are.”

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theatre critics in the U.S. by American Theatre Magazine. He has since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center’s Senior Arts Journalist.

Check out all of our 2020 Colorado New Play Summit Spotlights:

Check out our growing gallery of photos from the 2020 Colorado New Play Summit

A DCPA Theatre Company Commission

Cast and crew:

The 2020 Colorado New Play Summit is presented by AT&T, Sheri & Lee Archer/New Wave Enviro, The Joy S. Burns Commission in Women’s Playwriting, Daniel L. Ritchie, Semple Brown Design, Robert & Carole Slosky, and Transamerica.

Follow the DCPA on social media @DenverCenter and at the DCPA’s online NewsCenter.