DCPA NEWS CENTER

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

Enjoy the best stories and perspectives from the theatre world today.

The story of immigrants to the United States is often hazy in history. We learn about Columbus and later, the pilgrims, but not so much about other arrivals to our shores (or the African slaves, or the indigenous peoples who were already here). Immigration from China to America began in earnest in 1849, when gold was discovered in San Francisco, and waves of Chinese sailed to California with dreams of the riches they’d find in “Gold Mountain,” their name for the country. Alas, their dreams went mostly unrealized as they faced racial animosity.

Afong Moy

But 15 years before the gold rush in 1834, one Chinese young woman came to America not to make money for herself or her family, but for the two white men who brought her. Afong Moy, who was just 14 at the time, was put on display as “The Chinese Lady” with supposedly Chinese props and costumes and “performed” several times a day for paying audiences. She was apparently from a wealthy family because her feet were broken by binding, a sign of high social status. She was the first Chinese woman anyone in America had ever seen in person, a curiosity like in a carnival sideshow. Her appearances were accompanied by Atung, an English-speaking Chinese man who served as interpreter for the audience.

Afong Moy’s story was mostly forgotten, until playwright Lloyd Suh premiered his play, The Chinese Lady, in 2018. Now, theatre audiences in Denver can learn about Afong Moy through Suh’s two-person script, featuring Afong Moy and Atung.

Although newspaper articles and advertisements for Afong Moy ceased in 1850, Lloyd added to her story by having her speak to audiences as if she were on exhibit, into her old age, noting many of the anti-Chinese attacks that have been committed against the immigrants who came after her. She notes the October 31, 1880 racist riot that burned down Denver’s thriving Chinatown in what’s today LoDo.

Seema Sueko

But that local reference was not in the original script. Seema Sueko, director of The Chinese Lady, worked with Suh to add the reference to the Denver anti-Chinese riot. She feels part of the play’s mission is to make sure such incidents—like Afong Moy herself—aren’t forgotten and covered over by the mists of time.

“Lloyd’s real goal was that he wants people to add Afung Moy to their understanding of America,” Sueko says. “At the end of the day, if people walk out knowing this name Afong Moy, knowing she was here, and that Asian Americans have been here, you know, for centuries, that is his goal. But as he acknowledges, there’s very little in the historical record of any perspective that she held (about her situation). So he readily acknowledges in the script, ‘this is not my voice. This is not my clothes.’ This is not any of that. He hopes that she felt she was a cultural ambassador of some sort, you know?”

Sueko, who is half-Japanese and half-Pakistani and was raised in Hawaii, is familiar with Denver and the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. She directed the DCPA Theatre Company production of Vietgone, a powerful story about the Vietnamese refugee experience in the U.S. after the Viet Nam war, which was produced in 2018. She lives in the Washington, DC area, and acknowledges that history is incomplete everywhere. She notes that although the area around northern Virginia and D.C. have many historical markers about the Civil War, there isn’t any memorial to the Asians who fought on both side of the conflict.

Sueko has been learning more about Afong Moy to prepare for directing the play. She cites a book she’s currently reading, The Chinese Lady: Afong Moy in Early America by Nancy E. Davis, which she recommends for its thoroughness. “This came out in 2019, right around when Lloyd’s play first came out. She has done incredible research, in piecing together the historical record, based on newspaper clippings of the time, based on diaries of what people who gazed upon her wrote based on what else was going on.”

The book, like the play, puts Afong Moy in the context of her times. The play’s audiences won’t just get a profile of a young woman put into an unthinkable situation; they’ll get an introduction to the experiences and spirit of all Asian Americans.

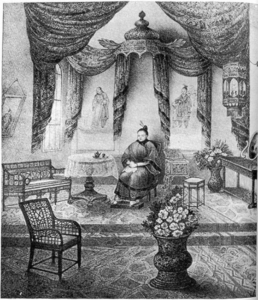

Afong Moy as depicted in an 1835 advertisement in The Charleston Mercury

Sueko first heard of Suh’s play when a woman she directed in Vietgone and had been friends with ever since was cast as Afong Moy. Early this year, the DCPA reached out to her and asked if she’d be interested in directing The Chinese Lady in Denver. “Of course, you know, the answer was ‘yes.’ Right away,” she says.

The challenge of directing The Chinese Lady, she adds, is that because it’s a two-person play, she had to find actors who were able to carry the dramatic and comedic elements of the script and have a strong relationship. Atung, the intrepeter/caretaker/servant has a complex relationship with Afong Moy. And since Afong Moy tells her story and the larger story of Chinese in America into the 20th century, it’s an epic story.

Sueko says she’s inspired by that epic story, and Suh’s telling of it.

“I guess maybe what I like to hold on to is her resilience,” Sueko says, “and also this hope, even though it gets reframed, even as her awareness of things grows. She still hopes for building bridges. In the end, she still thinks of herself as an ambassador.”

DETAILS

The Chinese Lady

Sep 9 – Oct 16 • Singleton Theatre

Tickets